By

James Delgado, SEARCH Inc.

Melanie Damour, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

Alexis Catsambis, Naval History and Heritage Command

Michael Brennan, SEARCH Inc.

Joe Hoyt, NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

Alicia Caporaso, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

Chris Horrell, Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement

Doug Jones, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

July 2, 2021

During the final dive of the 2021 ROV Shakedown, we explored the wreck of Humaitá (ex-USS Muskallunge), an American submarine that served in two navies between 1942 and 1968 (U.S. and Brazilian). Sunk during a live-fire target exercise off Long Island, New York, in 1968, remains of the submarine serve as habitat for bubblegum corals (Paragorgia sp.) and other marine animals and are protected from unauthorized disturbance by federal law. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 ROV Shakedown. Download largest version (mp4, 315 MB).

Entering service in March 1943 and sent to the Pacific, Muskallunge and its crew made seven war patrols, which included actions such as sinking enemy ships, rescuing fliers shot down on air raids who had parachuted into the sea, and surviving a prolonged depth charge attack off French Indochina (Vietnam). As American submarines targeted Japanese shipping across the Pacific, their crews switched from undersea torpedo attacks on large ships to surface attacks on the more frequent smaller ships. In one action, the crew fought off North Japan in heavy fog, damaging two ships during a running gunfight. One of Muskallunge’s gunners was killed by return gunfire, and two others were badly wounded.

At war’s end, Muskallunge was one of a group of submarines representing the U.S. Navy’s submarine forces at the surrender ceremonies in Tokyo Bay in September 1945. After the war, Muskallunge served with the Atlantic Reserve Fleet from 1947 to 1957. Then, the United States transferred the submarine to Brazil under loan as part of the Military Assistance Program.

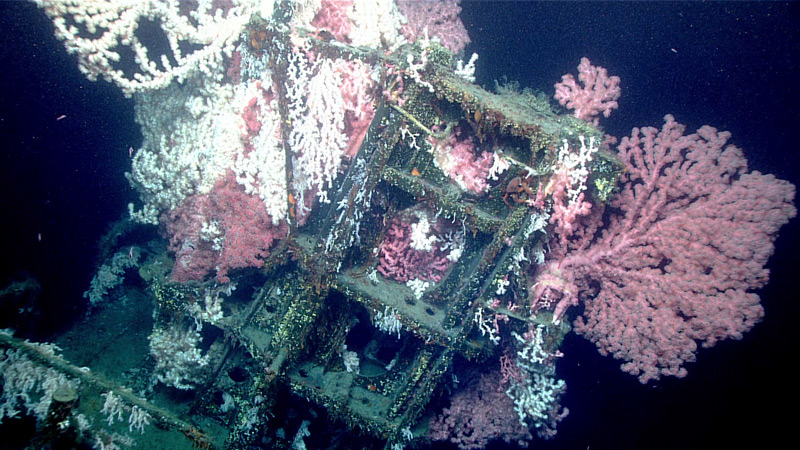

The wreck of USS Muskallunge serves as habitat for these bubblegum corals (Paragorgia sp.) and other marine animals. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 ROV Shakedown. Download largest version (jpg, 843 kb).

As Humaitá (S14), the submarine served with Brazilian forces until its return to the United States in early 1968. As new classes of submarines powered by nuclear reactors and capable of extended patrols and new types of undersea warfare had replaced the old wartime fleet boats, most of the veteran submarines were scrapped or sunk as targets. On July 9, 1968, a live-fire target exercise by USS Tench sank the former Muskallunge with torpedoes off Long Island, New York. Today, the sunken submarine remains protected from unauthorized disturbance by federal law and falls under the management of the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC).

Remembered by the veterans who served and their families, and by naval historians, Muskallunge was largely forgotten by the public, but visitors to museums throughout the country can tour examples of its class of submarine in San Francisco, California; Pearl Harbor, Hawaii; Manitowoc, Wisconsin; Mobile, Alabama; Fall River, Massachusetts; Muskegon, Michigan; Little Rock, Arkansas; Cleveland, Ohio; Galveston, Texas; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere.

The largest museum of lost ships is the sea. And this final dive of the expedition provided an excellent opportunity to try to visit one of its millions of shipwrecks up-close, for the first time.

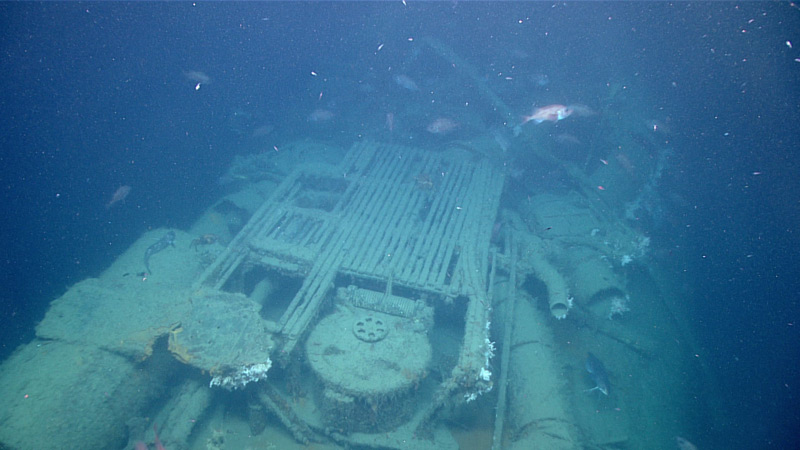

The smaller of the two targets turned out to be the stern section of USS Muskallunge, shown here with an escape hatch and preserved wood deck planking. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 ROV Shakedown. Download largest version (jpg, 508 kb).

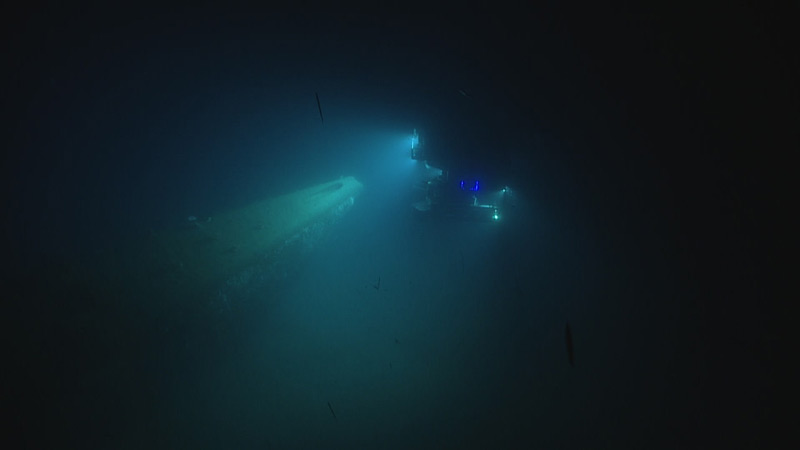

Scientists from government agencies, cultural resource management firms, and academia, as well as members of the public, were able to join the dive remotely, from shore, thanks to the power of telepresence. They eagerly watched the livestream as the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) pilots used the newly collected mapping data to skillfully guide ROVs Deep Discoverer and Seirios to the targets.

They were not disappointed. After reaching the seabed, the first indication that the targets were in fact USS Muskallunge was the presence of debris that likely blasted free of the submarine when it was sunk; a large section of riveted steel pipe used to ventilate the submarine while on the surface was the first piece to be found. Two larger sonar contacts, one about 60 meters (200 feet) long and the other about 30 meters (100 feet) long, proved to be the bow with much of the main body of the submarine and the stern, respectively.

The “S14” painted on the conning tower confirmed that this was USS Muskallunge. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 ROV Shakedown. Download largest version (jpg, 741 kb).

The shattered, partially crushed remains of a U.S. World War II-era submarine were the focus of the last dive of NOAA Ocean Exploration’s 2021 ROV Shakedown expedition aboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer on June 26. Using the hull-mounted multibeam sonar, the mapping team identified two interesting targets on the seabed in approximately 635 meters (2,000 feet) of water. The targets were in the vicinity of the sinking coordinates provided by the U.S. Navy’s NHHC of a veteran American submarine that had served in two navies between 1942 and 1968. Launched as USS Muskallunge (SS-262) in Groton, Connecticut, in 1942, the Gato-class submarine was one of nearly two hundred mass-produced American submarines, along with the Tench and Balao classes, that helped win World War II at sea.

USS Muskallunge in 1944. Image courtesy of the National Archives. Download largest version (jpg, 276 kb).

Torn in two by torpedo detonation, the sub sank quickly. Compartments and piping still filled with air imploded under pressure as the submarine hit the seabed at a depth six times deeper than its wartime-rated “crush depth.” Thick steel was dented like a crushed soda can, and the heavily built conning tower now sits at an angle, pulled down and forward.

After 53 years on the seabed, the submarine’s hull paint is still visible, and the white letters “S14” clearly identify the wreck as Humaitá, ex-USS Muskallunge. Standing proud on the seafloor, the submarine now serves as an artificial reef, hosting an abundance of marine life, including large colonies of bubblegum coral (Paragorgia sp.), Venus fly-trap anemones, worms, sponges, and numerous fish, squid, and other organisms. Evidence of a recent impact by fishing gear attests to an indirect human presence.

Remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer is seen here exploring the bow section of USS Muskallunge. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, 2021 ROV Shakedown. Download largest version (jpg, 64 kb).

The wreck speaks to a shared naval heritage that links the United States and Brazil, to the role of the sea as a strategic frontier and a battlefield, but also the overarching message of the importance of the ocean to all life on this planet, and as a still largely unexplored frontier. We are only beginning to understand the ecological role of underwater cultural heritage, and sites such as this attest to their additional value as habitat within the broader goals of ocean exploration and, ultimately, conservancy. Being some of the first human eyes to see the submarine where its remains lie on the seabed and how it has both influenced and been influenced by the marine environment after a half century is a privilege.

For more information, visit the Muskallunge entry in the NHHC's Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships .

In 2023, NOAA Ocean Exploration produced a photogrammetry model of the wreck of USS Muskallunge (SS-262).

Updated October 17, 2024