by Tim Shank, Ph.D., Orpheus Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Science Lead, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

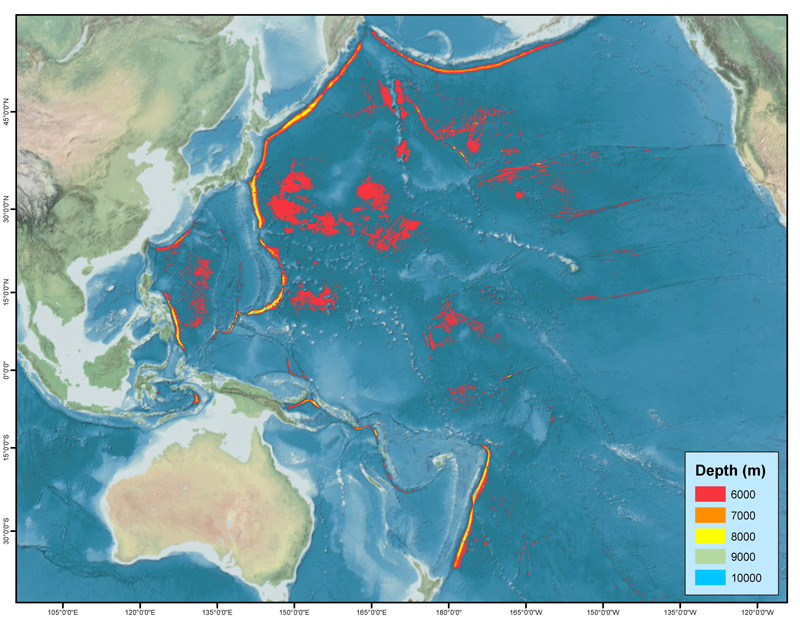

If there is any place on Earth that can be considered terra (or more accurately, aqua) incognita, it is the ocean’s hadal zone. Named after Hades, the Greek god of the underworld, the hadal zone extends from a depth of 6,000 to 11,000 meters (3.7 to 6.8 miles). It is made up primarily of widely separated ocean trenches and troughs that together occupy an area about half the size of Australia, but new regions of hadal seafloor are still being discovered.

Before 2014, much of our knowledge of life in the hadal zone came from two sampling campaigns in the 1950s: the Danish Galathea and the Soviet Vitjaz expeditions. These exploratory campaigns provided an initial catalog of hadal species, but they did not strategically or systematically sample at comparable depths or with sufficient replication to permit intra- or inter-trench comparisons upon which to draw ecological conclusions regarding demography or spatial population dynamics.

Figure 1: Even 10 kilometers (more than 6 miles) down, life finds a way. Photo © Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download image (gif, 6.5 MB).

Far from being devoid of life as originally perceived (Forbes & Austen 1859), subsequent opportunistic observations stimulated hypotheses that the hadal zone hosts a substantial diversity and abundance of life found only at those extreme depths (Wolff 1960; 1970), as well as oceanographic processes that link it to the surface and to nearby, shallower parts of the seafloor. There are also signs that physiological processes in hadal animals hold promise for developing new drugs and treatments for medical conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. However, as a result of historical factors and severe technical challenges associated with the extremes of pressure and distance (both from land and the sea surface), hadal systems remain among the most poorly explored habitats on Earth.

The most widely known patch of hadal seafloor is Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, the deepest known spot on Earth. In 2009, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution tested its first underwater vehicle capable of reaching full-ocean depth. While it was not a crewed submersible, it was extremely maneuverable and capable of conducting complex sampling and observing missions. That vehicle, the hybrid remotely operated vehicle Nereus , was lost in 2014 at nearly 10,000 meters depth in the Kermadec Trench north of New Zealand while conducting a lengthy survey of the seafloor and life there that had never been seen before.

Since the loss of Nereus , there has been a flurry of crewed dives to hadal regions, including a series of dives by Victor Vescovo in his submersible Limiting Factor to the deepest points in all five of Earth’s major ocean basins. But systematic, wide-ranging surveys of the hadal zone and life there have largely been on hold. The development of the new Orpheus class of autonomous underwater vehicles being tested on this expedition is hoped to invigorate hadal ocean science and scientific exploration of Earth’s greatest depths with new tools offering new capabilities and the hope of new discoveries.

A map of hadal regions in the Pacific shows that most of the ocean’s deep seafloor does not lie in the long subducting trenches that border tectonic plates, but mid-basin, where very little exploration has occurred. Illustration by WHOI Creative, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Download image (jpg, 1.5 MB).