by Stacey M. Williams, Institute for Socio-Ecological Research, Coastal Survey Solutions LLC

Jorge Garcia Sais, Reef Research Inc.

Queen snapper (Etelis oculatus, left) and silk snapper (Lutjanus vivanus, right) caught on the west coast of Puerto Rico by Mr. L. Román, who is pictured on the right. Image courtesy of L. Román. Download image (jpg, 256 KB).

One of the objectives of the Océano Profundo 2018 expedition is to explore the diversity and distribution of deep-sea benthic (seafloor) communities, particularly those found within deepwater snapper and grouper habitats, deep-sea coral and sponge habitats, and other vulnerable marine habitats. Through this approach, the expedition will not only collect new information in unexplored areas, but also information that is important to management efforts of the region.

Commercial fisheries support the livelihoods of many people in the Caribbean, as these fisheries are a vital source of employment and sustenance. Like many other Caribbean countries, the commercial fisheries in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands are small-scale or artisanal, as they occur mostly on the insular shelf and with the use of small boats. Catch consists primarily of shellfish (lobster) and finfish, with snappers and groupers being the most important finfish landed by weight.

On the west and east coast of Puerto Rico, the vast majority of snappers targeted by recreational and commercial fishers are found in deep waters ranging in depths from 160 to 450 meters (~500-1500 feet). The two main fish species found within these depth ranges are the silk snapper (Lutjanus vivanus) and queen snapper (Etelis oculatus).

Prey (shrimp, squid, fish) collected from the mouth of a queen snapper (Etelis oculatus) caught off Rincón, Puerto Rico. Image courtesy of L. Román. Download image (jpg, 491 KB).

Queen snapper landings have increased over time, while the landings of silk snapper have decreased. This decrease could be due to changes in the way fishermen catch silk snapper, which have changed from traps to vertical long lines, as well as recent implementations of management strategies, which now include seasonal closures (October to December) and annual catch limits. However, the life history, population dynamics, prey, and habitat of queen snapper are not well known, which complicates effective management of the fishery.

Researchers have hypothesized that the presence of deepwater fishes might be associated with areas of high biological biodiversity on the seafloor, since fishing gear are often lost or entangled in deep-sea corals and sponges at popular fishing spots. Within U.S. waters, studies on the distribution and species assemblages of Caribbean deepwater habitats are very limited when compared to the Gulf of Mexico or other parts in the North Atlantic Ocean. Most of the deepwater habitat characterization in the U.S. Caribbean was conducted more than 100 years ago. It was not until the late 20th century that scientists revisited exploring the deep sea to examine fisheries resources in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Little attention has been given to the deep-reef systems of the insular slope habitats. For example, deep reefs of the Mona Passage were not explored until 2015, when NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer conducted a mission to explore the biology and geology of Puerto Rico.

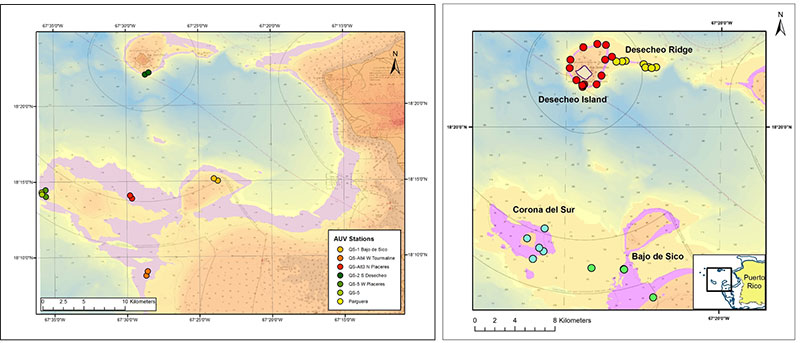

The submerged reefs of the Mona Passage and Desecheo Ridge are of particular interest to Caribbean fisheries, because they are the main habitats of the queen snapper. In 2015 and 2017, several researchers conducted fieldwork in the Mona Passage, Desecheo Ridge, and submerged seamounts of the west coast of Puerto Rico in order to explore deepwater grouper and snapper habitats. This work included surveys in the Mona Passage and off La Parguera using a SeaBed autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), as well as a Seamour remotely operated vehicle (ROV). The overall goal of these studies was not only to characterize the habitats qualitatively, but also quantitatively assess the biological diversity of both the benthic assemblages and fish communities at essential fishing grounds on the west coast of Puerto Rico.

Location of historic queen snapper and silk snapper surveys on the west coast of Puerto Rico, including AUV surveys in the Mona Passage in 2015 (left) and ROV surveys in 2017 (right). Image courtesy of Exploring Deep-sea Habitats off Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Download image (jpg, 639 KB).

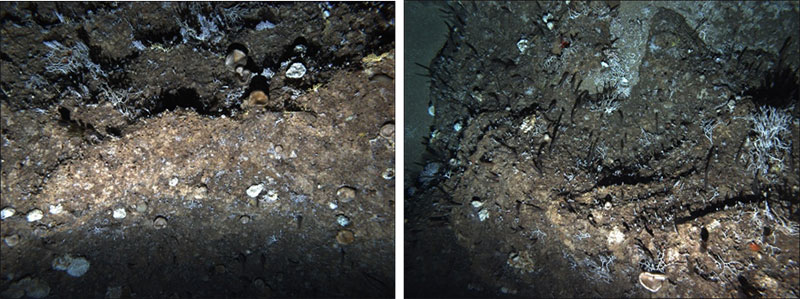

These studies showed that the density and relative composition of sessile (fixed or attached) benthic fauna varied markedly between locations. Availability of hard bottom, depth, slope, and distance from shore are proposed as the main factors regulating community structure. Like their shallower counterparts, benthic topography played a significant role in the presence of benthic organisms at these deepwater habitats. Areas with marked discontinuities in substrate (the surface on which animals live) and high topographic relief were hotspots of biological diversity and were inhabited by non-reef building corals and sponges.

At some sites in the Mona Passage, the combined substrate cover by scleractinian, antipatharian, hydrocorals, and soft corals was 15.5 percent over the total transect area (64 percent sand), with 43 percent cover on a suitable substrate, hard bottom. Such level of reef substrate cover by live ahermatypic (non-reef-building) corals is higher than that of reef-building coral assemblages from most shallow-reef coral reef systems in the natural reserves of Puerto Rico. The high percent of coral cover by diverse species is likely responsible for enhanced benthic productivity and ecosystem biodiversity of these areas.

Similar topographic seafloor features appear to be common throughout the Antillean Ridge, but are mostly unexplored, suggesting that such diverse deep reef communities may be widespread throughout the Mona Passage, Desecheo Ridge, and other submerged seamounts, and contribute significantly to the enhanced fishery production and biodiversity of this area. Several of these areas will be explored during the Océano Profundo 2018 expedition and thereby provide important insights into the deep reef biodiversity of this area.

Images taken from the SeaBed autonomous underwater vehicle in the Mona Passage at a depth of 270-280 meters (~900 feet). Images courtesy of J. Garcia Sais. Download image (jpg, 340 KB).