by Adam Skarke, Assistant Professor of Geology, Mississippi State University

May 1, 2018

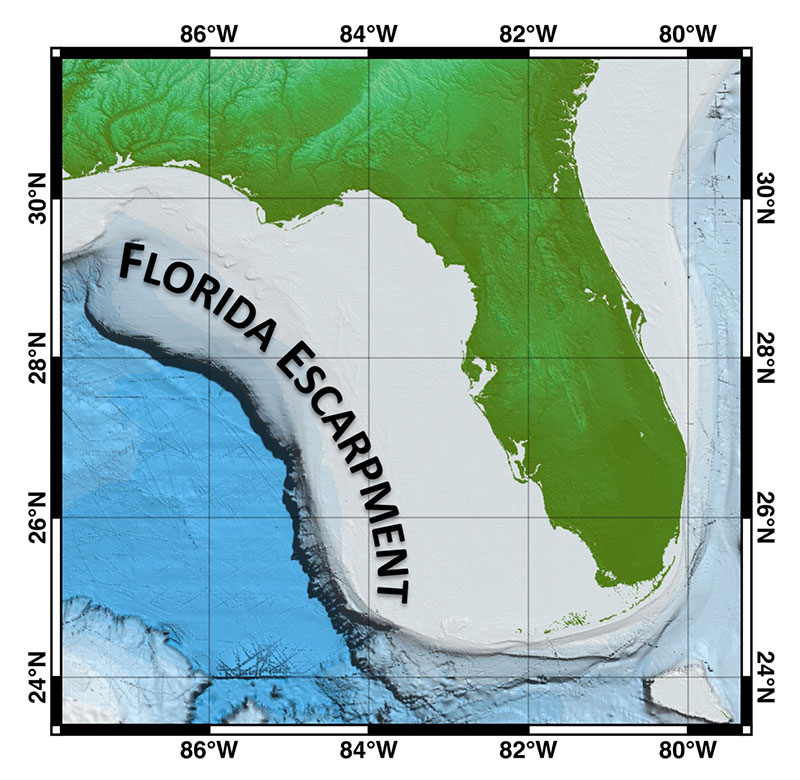

Figure 1: A bathymetric map of the eastern Gulf of Mexico showing the length of the Florida Escarpment from De Soto Canyon to the Florida Keys. Note the extent of the shallow Florida Platform surrounding the Florida Peninsula. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

If all goes according to plan, the final eight dives of the NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer Gulf of Mexico 2018 expedition will take place along a 900-kilometer (~560-mile) long cliff under the Gulf of Mexico, known as the Florida Escarpment (Figure 1). The Florida Escarpment is a very steep slope where the seafloor plunges rapidly from the relatively shallow waters of the west Florida continental shelf – less than 100 meters (~330 feet) deep – to the abyssal plain of the deep Gulf, over 3,000 meters (~9,840 feet) deep. The escarpment lies between 250 and 350 kilometers (~155 and 215 miles) off the west coast of Florida and extends from De Soto Canyon in the north to the Florida Keys in the south. The maximum relief of the escarpment is approximately 3,000 meters (~9,840 feet) and its slopes commonly exceed 60°, with some small portions approaching vertical (Figure 2). Due to the steepness of its terrain, rock is exposed along much of the escarpment, making it an ideal habitat for sessile organisms that require hard substrate, such as coral and sponges, as well as associated communities.

Figure 2: A perspective view of the bathymetry of the Florida Escarpment. Note the steep face of the escarpment and erosion canyons cut into it. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 426 KB).

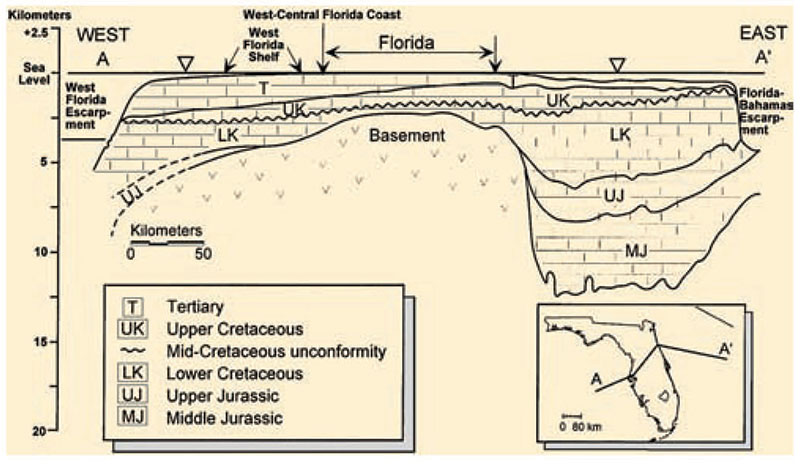

The Florida Escarpment is the western edge of a large carbonate platform that encompasses the Florida Peninsula. The platform is a tall underwater plateau (Figure 3) composed of carbonate rocks that were produced by biological organisms in warm, shallow, and tropical waters, very similar to the modern islands of the Bahamas. Over the course of 120 million years (between 180-60 million years ago), the ancient crustal blocks that form the deep basement under Florida gradually subsided deeper and deeper below the sea surface, allowing shallow reefs to build up vertically and form the steep-sided rim of the carbonate platform.

Figure 3: A profile across the Florida Platform showing the steep-sided thick carbonate deposits over the deeply subsided basement rock. Image courtesy of A. Hine, 2009. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

Initially, the reefs were built by ancient clams (rudists) and later stony corals (scleractinians), which form modern shallow-water reefs. The interior of the platform was filled by shallow lagoons, tidal flats, and low islands where organisms such as mollusks, foraminifera, bryozoans, and algae produced carbonate sedimentary grains ranging in size from mud to coarse sands. Periodically, seawater trapped on the top of the platform would evaporate and leave salt deposits between layers of carbonate sediment.

Over tens of millions of years, the sediment grains and the surrounding reefs slowly cemented together to form a platform of limestone and dolomite rock, with intermittent salt layers, that is between two and six kilometers (~1.25 and 3.75 miles) thick. A key characteristic of carbonate rock is that it can be readily dissolved by weak acids commonly found in surface and groundwater. Because of this, the interior of the Florida platform has an ever-growing interconnected network of dissolved cavities and caves that allow saline groundwater to easily flow through it.

Figure 4: Image of steeply inclined exposed rock on the Florida Escarpment from Dive 11 of the Gulf of Mexico 2018 expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

The morphology of the Florida Escarpment is a result of the underlying geology of the Florida Platform. The northern extent of the escarpment is composed of reef deposits from the original platform rim and limited erosional features, which were the result of downslope movement of rocks being weathered from the cliff. Farther south along the escarpment, the reef deposits have been eroded away, leaving the interior platform rocks exposed. This more substantial erosion has produced larger and more numerous canyons cutting into the escarpment face. It appears that this pronounced erosion was driven by rock dissolution and cliff collapse that may have resulted from discharge of groundwater along the Florida Escarpment. This is supported by research that has shown evidence of saline groundwater seeps at the base of the escarpment.

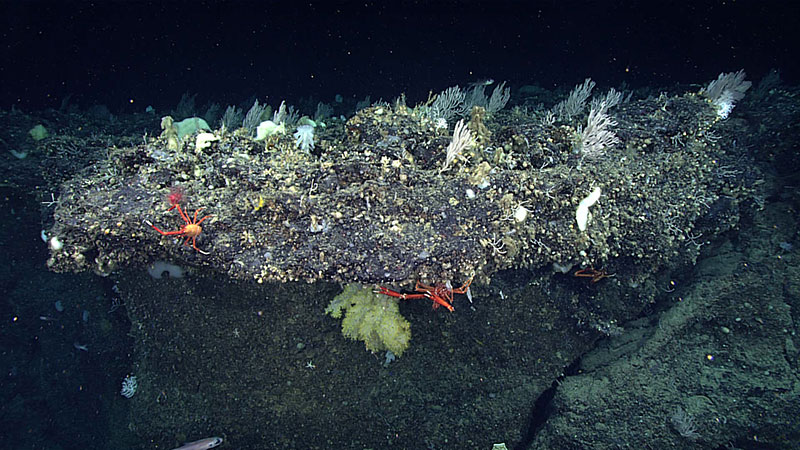

Due to its geological history and modern erosion processes, the Florida Escarpment has some of the steepest terrain (Figure 4) in the Gulf of Mexico, as well as some of the largest areas of exposed rock substrate. Because of this, it is an ideal habitat for sessile organisms, and hosts some of the densest and most diverse communities of corals found in the entire Gulf of Mexico (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Image of a dense and diverse coral community from Dive 11 of the Gulf of Mexico 2018 expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).