by Adam Skarke, Assistant Professor of Geology, Mississippi State University

April 27, 2018

Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (mp4, 29.7 MB).

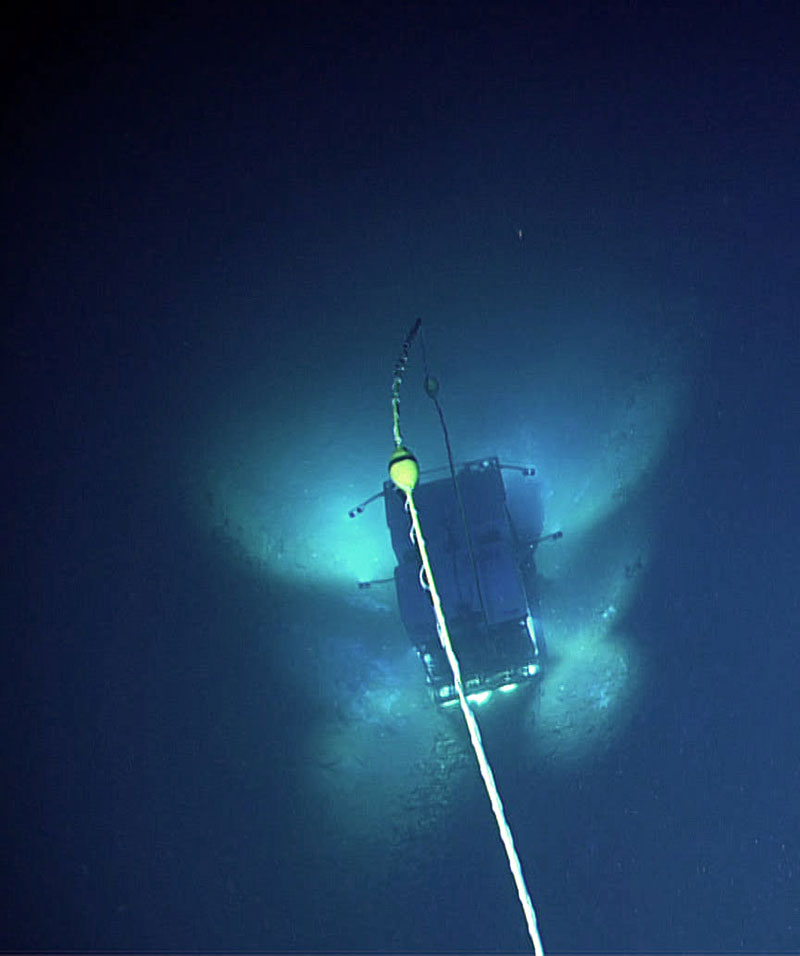

Halfway through Dive 06 of NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer 2018 expedition to the Gulf of Mexico, remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer (D2) crested a low rise on the seafloor and peered into the sediment-lined depression below (Figure 1). At the base of the depression was a small pool filled with dark blue water and surrounded by the bright white shells of dead mussels (Figure 2). The scientists and engineers in the control room immediately recognized the feature as a brine pool.

Figure 1: D2 observed a small brine pool at the base of a depression during Dive 06. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (jpg, 293 KB).

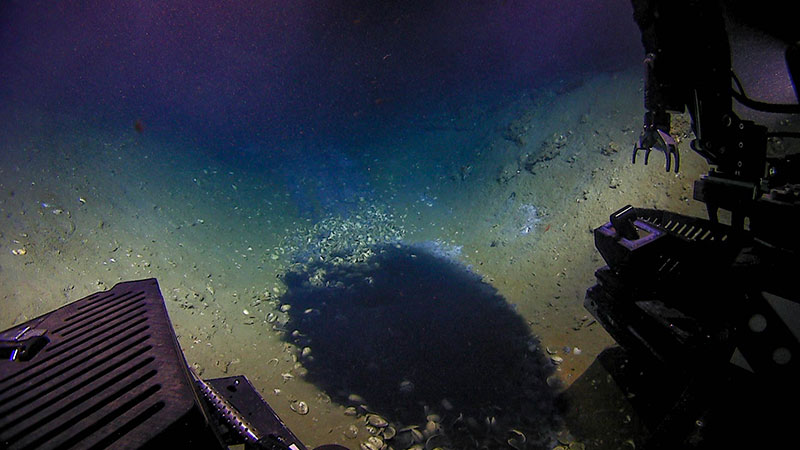

Panning slowly up from the pool, D2 imaged long, blue-gray-black streaks of stained sediment on the otherwise tan-colored slope above the brine pool. This stained sediment seemed to trace the path of flowing brine from a source above, down the slope, and into the pool below–an undersea brine waterfall (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Brine pool observed on Dive 06. Note the surrounding mussel shells and blue staining of sediment above the pool. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (jpg, 681 KB).

Figure 3: Panning up from the pool, D2 imaged long, blue-gray-black streaks of stained sediment on the otherwise tan-colored slope above the brine pool. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download map (jpg, 799 KB).

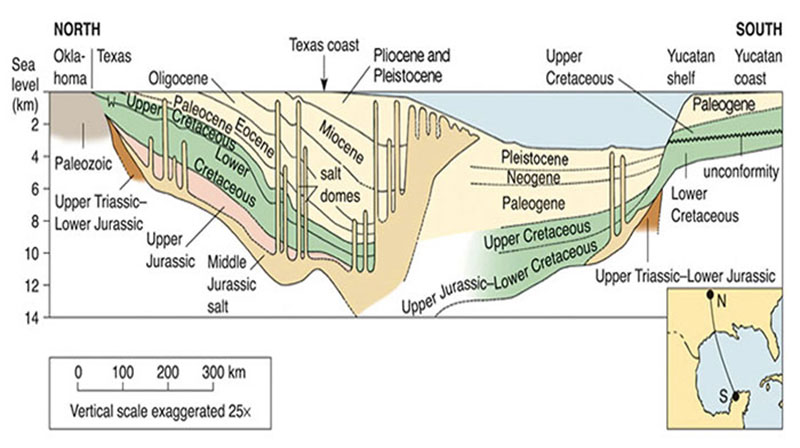

The presence of dense, highly concentrated brine on the Gulf of Mexico seafloor is a result of unique geologic processes in the region. Salt deposited over 180 million years ago during the Jurassic Period has deformed plastically (like modeling clay), under the pressure of overlying rock, and cut upwards towards the seafloor in columns and ridges known as diapirs (Figure 4). As these diapirs approach the seafloor from below, they create faults and fractures in the overlying rocks and sediment that allow seawater to contact the salt. When that occurs, the salt dissolves and forms a concentrated brine fluid, many times saltier than seawater, that can flow out onto the seafloor. Once this dense fluid emerges from faults and fractures in the seafloor, it moves downslope as brine rivers and waterfalls to fill in low lying areas with pools and lakes.

Figure 4: A cross section of the geologic formations under the Gulf of Mexico. Note the abundant diapirs of Jurassic salt cutting upwards towards the seafloor through overlying sediment on the slope south of the Texas coast. Image courtesy of H. Levin, 2013. Download larger version (jpg, 150 KB).

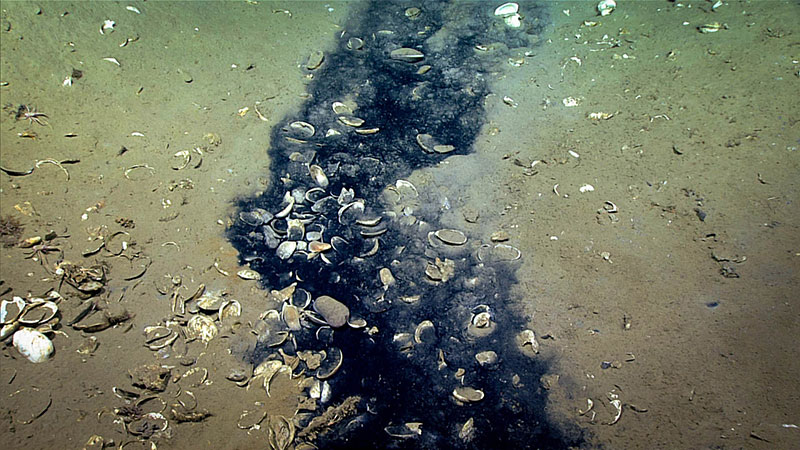

Brine pools are commonly rimmed by dense beds of chemosynthetic mussels, which contain symbiotic bacteria that consume methane that is often found in high concentrations within the brine. Accordingly, brine pools often support dense chemosynthetic communities. The brine pool observed on Dive 06 had abundant dead mussel shells surrounding its edge, as well as in the brine (Figure 5), suggesting that a chemosynthetic community was once present, but is now no longer active.

Figure 5: The brine pool observed on Dive 06 had abundant dead mussel shells surrounding its edge as well as in the brine, suggesting that a chemosynthetic community was once present, but is now no longer active. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2018. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

For additional information on brine pools, please see the Mission Log from the Gulf of Mexico 2002 expedition.