By Charles Messing, Expedition Co-science Lead, Nova Southeastern University

December 7, 2017

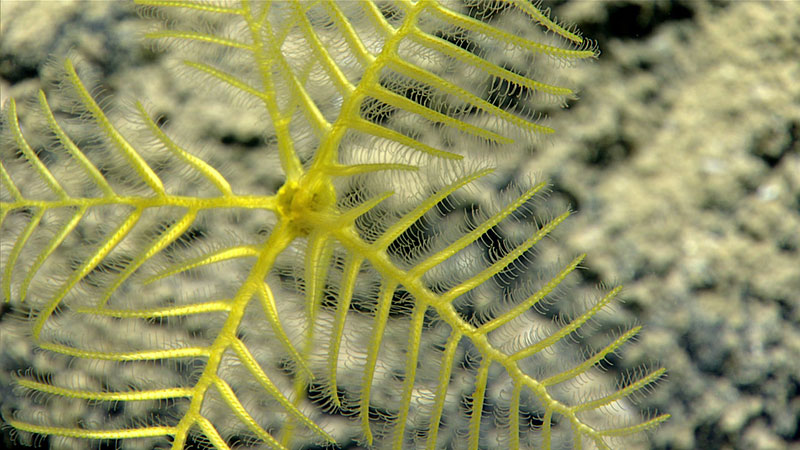

This sea lily may be the poorly known Monachocrinus caribbeus, the only member of its family, Bathycrinidae, previously recorded from the Gulf of Mexico. We found large numbers of these crinoids in some areas attached to hard elevated substrates. It displays the parabolic filtration fan posture characteristic of most stalked crinoids, with arms curved back into the current and mouth oriented downcurrent (to right in this image). Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download larger version (jpg, 658 KB).

Sea lilies and feather stars are among the strangest creatures that Okeanos Explorer has encountered during this expedition. Their formal name, crinoid, means lily-like (thus, one of their common names), and although they appear superficially plant-like, they are animals, complete with digestive and nervous systems. Their closest relatives are the sea stars, sea urchins, brittle stars, and sea cucumbers. Together, these five groups form the major branch of the animal kingdom called the echinoderms (spiny-skin). Members have a basic five-sided symmetry, calcareous skeleton, and unique internal canal system and ligamentary tissue.

Most of a crinoid’s body is a series of small calcium carbonate plates (ossicles) held together by ligaments and, in some cases, muscles. The basic body plan is a central cup of plates that houses the internal organs and is supported by a stalk composed of a stacked series of ossicles. Unlike the arrangement in sea stars, both the mouth and anus of a crinoid lie on the upper surface. Five arms arise from the cup and bear fine side branches (pinnules) that give each arm a feather-like appearance. Although some crinoids have only five arms, in most species each arm divides one or more times near its base, so that some species have 10 arms and others as many as 180.

Feather stars are sometimes incorrectly called unstalked crinoids. Larvae do develop a stalk after they settle out of the plankton, but they shed it when still very small. A single remaining uppermost stalk segment, the centrodorsal, bears hook-like cirri for clinging to the seafloor or other invertebrates, such as corals and sponges. The long prehensile cirri of this feather star are characteristic of family Thalassometridae, and this is also likely a new species. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download larger version (jpg, 895 KB).

Crinoid skeletal remains are among the most abundant and important of fossils. They arose during the early Paleozoic Era and were so abundant that their fossils produced vast limestone deposits in many places around the world, including the American Midwest. More than 5,000 fossil species have been described. Crinoids have declined in diversity since their peak some 300 million years ago, but over 650 living species are known, and they are still enormously abundant in many marine habitats, from shallow coral reefs to the floors of oceanic trenches. Nevertheless, they remain the least understood of living echinoderms.

We use the informal names "sea lily" for those species that retain a stalk as adults and "feather star" for those crinoids that lose the stalk as small juveniles. However, these are not strict taxonomic groupings. It turns out that the stalk has been repeatedly lost and retained in adults several times. However, in modern seas, although feather stars occur from just below the tide line in some places to great depths, sea lilies no longer occur in shallow water; the shallowest species, Metacrinus rotundus, can be found at a depth of 100 meters off Japan.

All crinoids are suspension feeders. The fine, threadlike tube feet lining the side branches of the arms flick drifting food particles into a groove, from where cilia carry the food to the central mouth. This member of Hyocrinidae, the first record of this family from the tropical western Atlantic, is likely a species new to science. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico 2017. Download larger version (jpg, 991 KB).

All crinoids are suspension feeders, subsisting on the smorgasbord of small plankton and detritus that drifts past their outstretched arms. Small fingerlike tube feet (the same structures that line the undersides of sea star arms but without the sucker tips) line the pinnules and flick passing food particles into a groove, where microscopic hairs (cilia) carry the food particles to the central mouth, conveyor-belt style.

Most sea lilies array their arms in a bowl or dish with the arm tips flexed back into the current and the top of the stalk bent so that the central mouth faces away from the current. They use their unique echinoderm ligamentary tissue to lock the arms in place, which does not require expending energy. If the current gets too strong, or the crinoid is disturbed or attacked (some sea urchins and sea stars feed on crinoids), the ligaments go flaccid and muscles on the grooved side collapse the arms together for protection.

Although some crinoids are permanently attached to hard substrates by a holdfast at the bottom of the stalk (much like a sea fan or black coral), or anchor in sediment via rootlike structures, the feather stars and some of the sea lilies have hooklike cirri that can release their hold on the seafloor. These species can use their arms to crawl, and some feather stars can swim.

This expedition has already found a wealth of crinoids, including representatives of seven families. Some have appeared in unexpected abundance, and we have found at least two new species. One of these new species represents the first record of its family from the tropical western Atlantic Ocean. As we are only half-way through the trip, more surprises may await.