By Eric Mittelstaedt, Ph.D., Assistant Professor - Department of Geological Sciences, University of Idaho

September 16, 2017

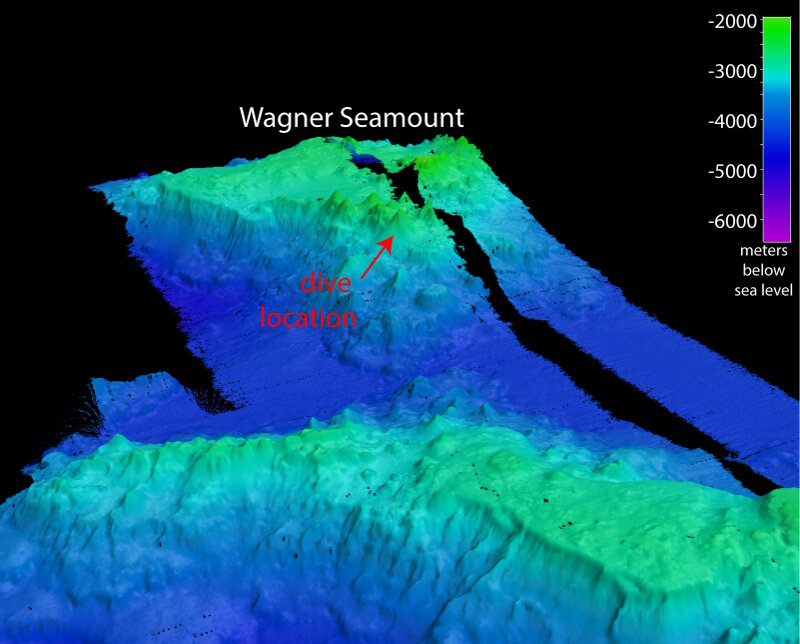

Map of Wagner Seamount showing the location of our remotely operated vehicle dive. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Deep-Sea Symphony: Exploring the Musicians Seamounts. Download larger version (jpg, 961 KB).

My name is Eric Mittelstaedt. I am a geophysicist from the University of Idaho who specializes in studying the ocean floor to find out what it can tell us about plate tectonics and the evolution of the Earth’s surface. During the Deep-Sea Symphony expedition, my goal was to collect rock samples and to use new maps of the seamounts of the Musicians seamount chain to improve our understanding of the origin of volcanoes on the seafloor.

During my first dive (indeed, my first experience as a participating scientist with NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer!), we were diving on a small volcano called Wagner Seamount and found something that geologically was unexpected; easily the best part about going into the field – you always find something unexpected!

Generally, lava erupts onto the seafloor in the form of “pillow lavas.” Pillow lavas have a shape much like their name, they are bulbous and round. They take this shape because their surface cools very rapidly when it comes into contact with seawater, creating a crust that is then blown up like a balloon by more lava as it pushes out from the seafloor into the inflated crust.

On my first dive at the Musicians, however, we did not see a single pillow lava! The frozen lavas we observed on the seafloor were smooth and looked like they had flowed across the seafloor like a pancake, a form generally known as a sheet flow. Sheet flows happen on the seafloor when lava moves rapidly relative to the amount of time it takes to cool and form an exterior crust. Rapid lava flows tend to occur in one of two situations:

Smooth lava flows like these tend to indicate rapid movement of lava as it erupts either due to erupting on a steep slope or the expulsion of lots of lava from a volcano in a short period of time. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Deep-Sea Symphony: Exploring the Musicians Seamounts. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

In the case of this volcano, it seems like the lava morphology might have been primarily a function of the eruption rate because sheet flows were present even at the summit, where the slope of the seafloor was shallow. From this observation, we know that it was likely a very active volcano at the time of the eruption of these lavas! Just by observing the form of the lavas, we learned that this volcano erupted lavas quickly, an observation I plan to compare to other volcanoes along the Musicians chain to help us learn about how the chain of seamounts may have formed.

We had to sample this lava to help us learn more about this very rapidly erupting volcanic feature on Wagner Seamount. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Deep-Sea Symphony: Exploring the Musicians Seamounts. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

Participating in this expedition to the Musicians Seamounts was quite a departure from my normal field experience! Commonly, when I am part of a ship-based expedition, I must travel to the ship and remain at sea for several weeks. Although rewarding, such a mission is time consuming and can be difficult to arrange during the school year when I have classes to teach.

Being able to participate for a focused period was a real treat and allowed me to collect data that will help further my research, while still being able to teach and remain close to home. This type of situation is where the telepresence capabilities of the Okeanos Explorer really shine; it brings researchers together from all over the world to simultaneously explore the seafloor in a way not possible even 15 years ago.