By Bruce Mundy - NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center

September 12, 2017

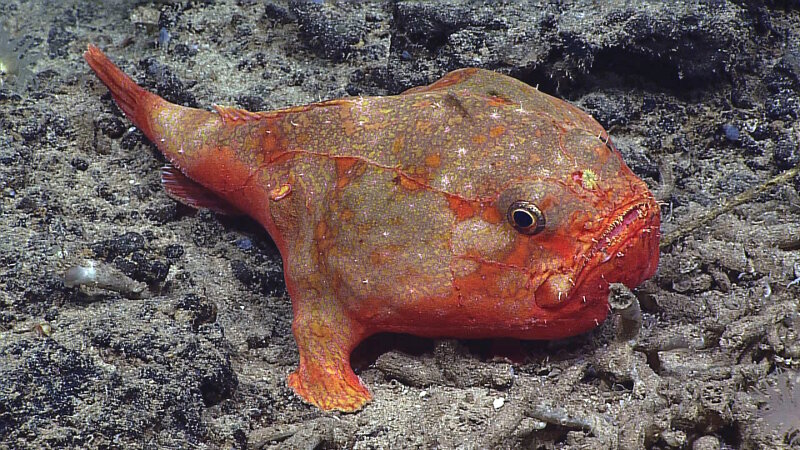

This sea toad or coffinfish (Chaunacops species) was seen at a depth of about 3,148 meters (1.96 miles), during a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dive at a seamount ridge, dubbed “Beach Ridge,” in the Musicians Seamount group northeast of Oʼahu, Hawaiian Islands. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Deep-Sea Symphony: Exploring the Musicians Seamounts. Download larger version (jpg, 680 KB).

On September 8, 2017, this bright-red sea toad or coffinfish (Chaunacops species) was seen at a depth of 3,148 meters (about 1.96 miles) during a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dive at a seamount ridge, dubbed “Beach Ridge,” in the Musicians Seamount group northeast of Oʼahu, Hawaiian Islands. Its identity is a mystery.

Sea toads, or coffinfish (Chaunacidae), are among the more unusual fish occasionally observed during the Okeanos Explorer’s ROV expeditions in the central Pacific. They are deepwater relatives of the frogfish seen by attentive divers in tropical waters and of the goosefish or monkfish of the North Atlantic Ocean.

This Commerson’s frogfish (Antennarius commersoni), photographed at SCUBA-diving depths off Oʼahu, has its lure folded back along its head so that it cannot be seen. Image courtesy of Bruce C. Mundy, NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center. Download larger version (jpg, 3.9 MB).

All of these fishes and others in their order (Lophiiformes) have a distinctive luring apparatus on their heads and an unusual position for their gill openings. The lure is a modified ray of the dorsal fin (the fin on the back) that is displaced much further forward than in most fishes. The several lophiiform families have different sizes, positions and shapes for this lure. The gill openings of lophiiforms are placed behind the pectoral fins (the paired fins behind the head) instead of the usual position in front of those fins and have smaller openings than in most fishes. Some lophiiforms can rapidly expel water through their narrow gill openings to create a jet propulsion that allows rapid swimming and escape for these normally sedentary fish.

Frogfishes (Antennariidae) are shallow-water masters of camouflage related to sea toads. They are popular subjects for underwater photographers because of their unusual shapes and colors, and because they rarely move. They have a lure on their snouts, often on a long stalk, that they use to attract small animals that they eat.

Sea toads are characterized by having a small lure on a short stalk, placed in a depression on the head between their eyes. The lure is rounded with numerous, small filaments that make it look like a tiny mop. Frogfishes and goosefishes living in shallow, sunlit depths wave their long-stalked lures to attract small animals that are their prey.

Sea toads live at depths where there is little or no sunlight to let their lures be seen. How do sea toads use their lure to attract prey? We do not know the answer, but we can guess.

A Chaunax umbrinus photographed during an Okeanos Explorer ROV dive on the southwest coast of Niʼihau, Hawaiʼi, between 312-538 meters (1024-1765 feet). Chaunax species differ from Chaunacops species by having smaller, more numerous sensory pits on the head and body and usually by having much smaller prickles on the body, among other characteristics. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Hohonu Moana 2015: Exploring Deep Waters off Hawai’i. Download larger version (jpg, 1.9 MB).

Open-water (pelagic) anglerfishes that live in the deep ocean have lures on long stalks that produce light (bioluminescence). These anglerfishes certainly use their lures as lighted bait to attract food. Sea toads have been described in some publications as having bioluminescent lures, but there is no evidence for that and it is probably unjustified extrapolation from what is known about the bathypelagic anglerfishes.

There is evidence that the batfishes (Ogcocephalidae), close relatives of sea toads that live in the same habitats, have glands in their lures that produce odors which attract prey. It seems likely that sea toads are similar to the batfishes in how they use their lures. However, we no almost nothing about the biology of sea toads other than where they live, so the way that their lures function remains a mystery for now.

There are two genera in the Chaunacidae family. Chaunax has 25 described species that live in the upper bathyal regions of the oceans between 300 and 6,500 feet, below the depths reached by most SCUBA divers. Chaunacops has four described species that are usually found deeper than Chaunax species, although the depth ranges of two genera overlap. There are likely undescribed species in both genera that have yet to be discovered.

A Chaunacops coloratus photographed during an ROV Deep Discoverer dive at about 2,239 meters (7,346 feet) on a flat-topped seamount (guyot) west of Wake Atoll on August 6, 2016. This individual sat in a characteristic posture for the species on sediment next to a rock. Image courtesy NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Deepwater Wonders of Wake. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

The Chaunacops species that we have most often seen during the central Pacific Okeanos Explorer ROV expeditions is C. coloratus. Most individuals are pink or pinkish-red, with prominent prickles on the head and body, and short cirri. They are usually, but not always, seen in a characteristic posture with one pectoral fin braced like a hand against a rock and the other placed down on sand or sediment.

The bright-red Chaunacops observed on September 8 looked different from the C. coloratus seen in other Okeanos Explorer Pacific expeditions by having a brighter color, larger cirri, and smaller or no prickles on its back. We do not know if these differences were caused by variation among individuals of the same species, by variation among different sizes or maturation stages of the same species, or by differences between species. If the differences were due to variation between species, we may have found a second, undescribed species of Chaunacops in the Hawaiian Islands.

This bright-red Chaunacops observed during the Deep-Sea Symphony expedition differed from those usually seen by having a brighter color, larger cirri, and smaller or no prickles on its back. Image courtesy NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Deep-Sea Symphony: Exploring the Musicians Seamounts. Download larger version (jpg, 349 KB).

However, this illustrates an important point about explorations of deep-sea biology – we cannot verify what species we see without collecting specimens that can be examined in detail. Video records alone do not allow for accurate species identifications in most cases, and they certainly do not allow for the identification and description of new species.

Although the ROV Deep Discoverer can use its mechanical arm to collect specimens of non-swimming organisms like corals and sponges that are thought to be new species, it cannot collect organisms that swim. Thus, the observation of the bright red Chaunacops gives us another deep-sea mystery whose solution will have to await further exploration with tools that allow specimens to be collected.