By Amanda N. Netburn, NOAA Cooperative Institute for Ocean Exploration, Research, and Technology (Florida Atlantic University)

May 9, 2017

On May 6, after finishing exploration of the seafloor within the Jarvis Unit of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, now known as Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument, we conducted a series of midwater transects from 1,400 to 300 meters (~4,595 to 985 feet). Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (mp4, 24.9 MB)..

The water column is one of the most underexplored environments on the planet. As a follower of NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer expeditions, you may have seen streaks of particles, as well as transparent and small creatures, that we pass on the way down and back up from every dive. The majority of our dives are focused on surveying the seafloor to understand the habitat and life there. However, if we slow down and take a closer look, we find that there is abundant life throughout the full water column.

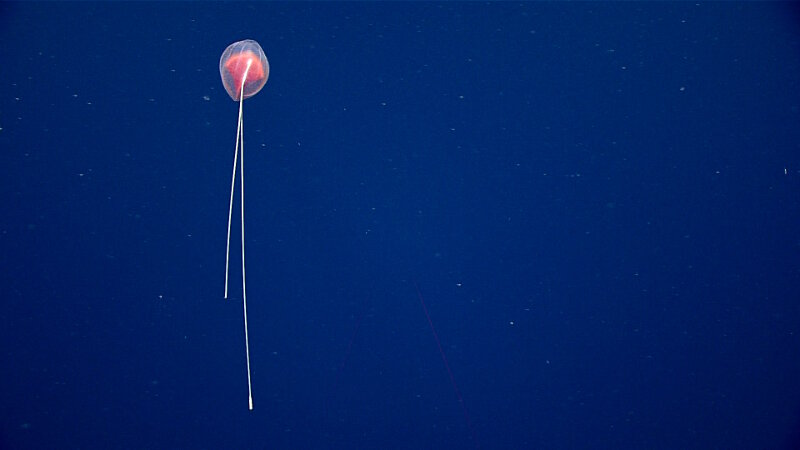

It seems that this jellyfish can really pack a punch – the thick bright ends of its tentacles are where the nematocysts (stinging cells) are especially dense. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 466 KB).

Long tentacles, like on this anthomedusa jellyfish, are used to sting and capture small prey items. Many animals in the deep pelagic have one or more long tentacles to help capture food or particles drifting by. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 771 KB).

The distribution of fauna in the water column can feel sparse compared to the seafloor. Yet, if you took all that water away, the biomass you would be left with would be many times greater than that of the seafloor fauna. From the surface to the seafloor, the water column is the largest habitat on the planet for multicellular animals. This is because seafloor and land-based animals are limited in space to mostly two-dimensional habitats; but midwater animals have the full volume of the water column available to them and can move freely about in all three dimensions.

And move about, they do! If you take a peek at any single spot in the water in one moment in time, minutes later you will find something different in that same space. This is because even weak currents will move poor swimmers like zooplankton ("drifting animals") around in the ocean. For the swimmers (e.g., fish, sharks, whales, etc.), it is because they are almost always moving.

Another anthomedusa jellyfish. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 514 KB).

Narcomedusa with tentacles extended. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 964 KB).

Migrations are common in the open ocean. Tunas, sharks, and some marine mammals can migrate thousands of miles, moving freely between countries' boundaries. Many smaller animals migrate every single night in the greatest migration on the planet. These animals live in deeper layers of the water, typically 200-1,000 meterse (or 655-3,280 feet), hiding in the darkness of the deep open ocean and swimming up to the surface at night to feed.

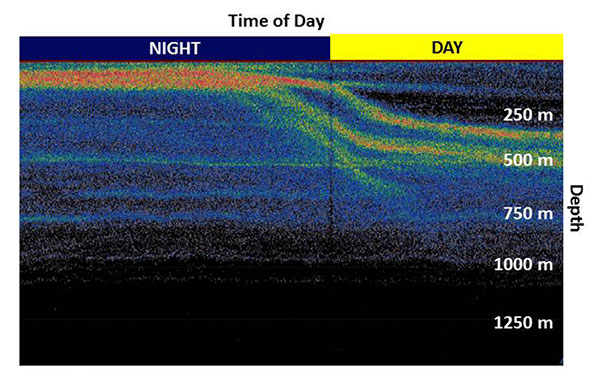

An echogram, showing acoustic backscatter. The horizontal axis is time, with the most recent recording on the righthand side of the plot. Note the layer of highest backscatter (reds and yellows) moved from the surface to over 300 m depth in the morning. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download image (jpg, 71 KB).

This daily migration can be observed using active acoustics. By regularly transmitting sound beams through the water column, we can see where animals are distributed because they reflect some of the sound back to the ship. Through this migration, these animals move massive quantities of energy from the surface to the deep ocean in what is known as the "carbon pump." Algae near the surface incorporate carbon dioxide into organic matter through photosynthesis and are eaten by small zooplankton, which in turn are eaten by larger animals. When they swim down in the morning, they move all that organic matter to the deep sea, where eventually it sinks as marine snow to the seafloor.

The water column is one of the most underexplored environments on the planet. You are quite unlikely to have seen many of the creatures that live there. Many of the animals that live in the water column have ways to produce light; this is called bioluminescence. This capability exists for three different reasons: (1) lures to attract prey (e.g., anglerfish); (2) decoys to throw off predators (e.g., a squid releasing glowing ink); and (3) for intra-species identification (to find a mate).

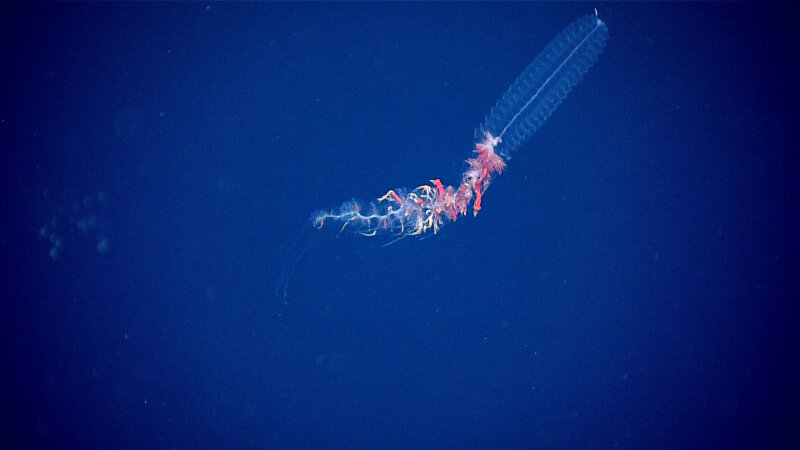

A physonect siphonophore. Siphonophores are colonial relatives of jellyfish. At the top of this colony, you can see a small pneumatophore, a gas-filled float, that helps the animal stay upright. Below this are the swimming bells, individuals that help propel the colony through the water. The final section contains both reproductive and feeding individuals. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

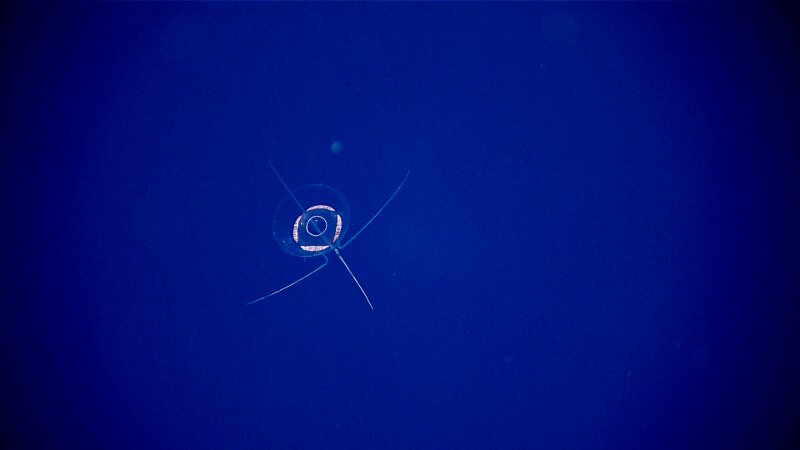

A cydippid ctenophore (comb jelly). Ctenophores come in a surprising number of different shapes, but all have in common eight rows of ctenes (or combs) that are rows of ciliated cells. As these ctenes beat, they can sometimes cause beautiful rainbow-like refractions that many people mistake for bioluminescence. This ctenophore has two long tentacles that help it to capture prey. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 893 KB).

Scientists are still developing best methods for detecting bioluminescence and understanding its role in the ocean. Many midwater animals are gelatinous – they have high water content and are transparent. Gelatinous animals fall apart when collected in nets, the traditional way of surveying for water column animals. Because of this, current knowledge is sparse about behavior, feeding, reproduction, and physiology for many of the most abundant fauna in the ocean.

In summary, we know very little about the water column, despite the huge biomass that lives there and its importance to the global carbon and other biogeochemical cycles. The exploration we conduct on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer during this expedition is providing a first glimpse into the water column at some of the most remote and unexplored places on the planet.

We were very excited to see this doliolid in the water column. Doliolids are a type of tunicate, related to salps and sea squirts. The "tail" trailing behind it is actually a series of clones – doliolids can reproduce through both sexual and asexual reproduction. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 946 KB).