By Chris Mah - Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

May 8, 2017

Ever since I was a volunteer in high school – and after I became a scientist – one of the questions about sea stars and their relatives I am asked most frequently is: "How do they eat?"

There's something about the weirdness of these animals, with their five-part symmetry and downward facing mouths, that defies the "common wisdom" of simply looking at a species and immediately being able to identify the mouth, or any other structure, that is more easily recognized on a bilaterally symmetrical animal such as a fish or a cat.

I study sea stars – also called starfish or asteroids – but I am also familiar with their closely related cousins in the class Ophiuroidea – also known as brittle stars, serpent, and basket stars.

Sea stars occupy an important role in marine ecology, from the familiar intertidal species, such as Asterias (Common Atlantic stars) and Pisaster (e.g., Ochre stars) to deep-sea species. Sea stars can exert a significant influence on other species within these ecosystems, similar to the manner in which wolves affect forests.

Brittle stars, distant relatives of sea stars, often occur in huge abundance. Although their ecological roles are more poorly understood, they are a successful group that are found in a multitude of marine settings, from hiding in rocky reefs to carpeting the deep-sea bottom – or to living on jellyfish!

Over the past week, I've been part of the shoreside science team providing identification and biological assistance to the research team on the current NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer expedition. We have seen some fairly exciting feeding observations in both sea stars AND brittle stars!

A highlight of Dive 05 at Jarvis Island was observing a group of ophiuroids capture and eat a squid (Abralia sp.) that was swimming by. Our science team was shocked to see this behavior from a brittlestar. This interaction helps us understand a little bit more about bentho-pelagic coupling in this region. Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (mp4, 1.8 MB).

On Saturday, we were delighted to watch a VERY rare occurrence. We watched a brittle star, in the family Ophiotrichidae, CAPTURE and FEED upon MOVING prey – a small squid in the genus Abralia!

MOST ophiuroids have been observed either scavenging or feeding by some other passive means, such as filter feeding, usually by holding their arms up into the water current.

In fact, it was BECAUSE we expect them to filter feed that we were SO surprised when we saw one GRAB and attack this squid!! This was immediately followed by SEVERAL other individual brittle stars joining in the attack on the squid once it was subdued!

This was VERY unexpected! As it turns out, this behavior has been recorded BEFORE in both deep-sea and shallow-water brittle stars! However, it is not seen very often. It does appear to be quite brutal when it does happen, though.

Following the capture by an arm loop, the animals jumped onto the prey and subdued it. Read one account here . And here's a post including multiple links to deep and shallow brittle star feeding

The attack during the current Okeanos expedition is the first time this behavior has been reported since 1998! An AMAZING occurrence!

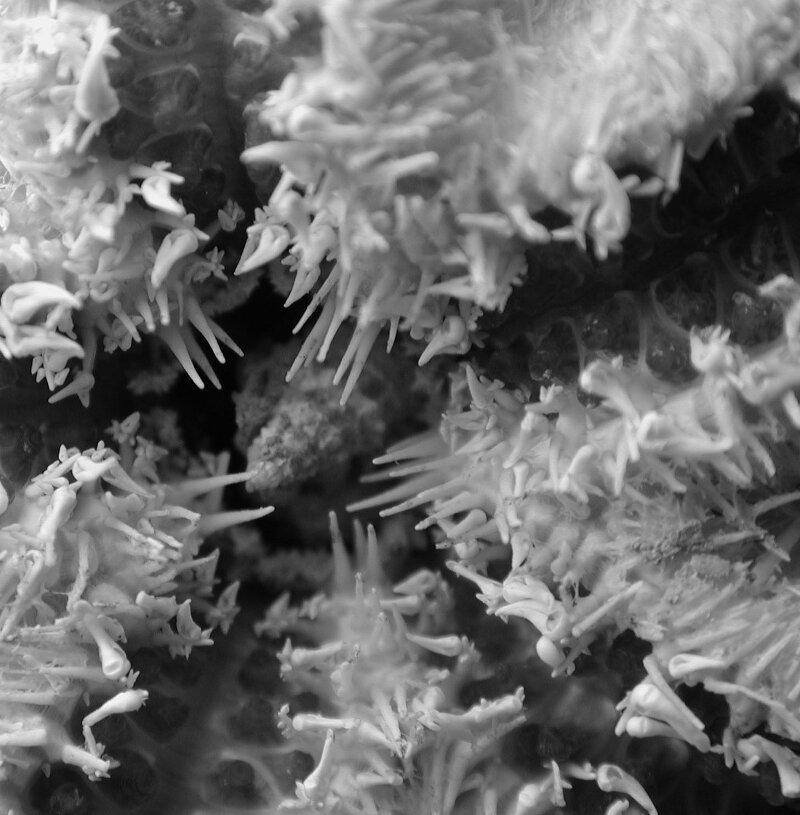

A goniasterid in the genus Circeaster feeding on a primnoid coral. This observation was made on Dive 07 of the expedition at the seamount dubbed "Whaley." Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

A seastar in the family Goniasteridae, genus Hippasteria, with an arm menacing this tiny little octocoral off to the side at "Whaley Seamount." Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 2.2 MB).

Perhaps a bit more predictable, in terms of feeding behavior, was our observation of this goniasterid, in the genus Circeaster, feeding on a primnoid coral.

This gorgeous shot shows the stomach of the goniasterid extended out onto the coral, and feeding on the polyps and tissue of the prey; you can also see the tube feet gripping the coral skeleton.

Based on an observation by the biology co-lead, Scott France, these sea stars can sometimes remain on deep-sea corals for over a YEAR!

Zoroaster on "Whaley" seamount, partially buried in the sediment. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

I performed a study of the gut contents based on specimens of these animals in the National Museum of Natural History several years ago. Based on this research, they seemed to be feeding mostly on sediment and tiny animals in the sediment, especially snails and other mollusks. Image courtesy of Chris Mah. Download larger version (jpg, 383 KB).

Zoroasterids are a group of deep-sea asteroids that occur all over the world. Many of them get quite big (up to two feet across) and are often bristling with sharp spines. Fossils of zoroasterid-like sea stars can be found from the Jurassic period, 155-160 million years ago!

If you look at this animal in the sediment, it is partially buried with its disk and arms; sediment is pushed aside and the body set into a depression in the sediment. It is likely that this animal is feeding, perhaps using tube feet, spines, or even little claws (called pedicellariae) to help feed!

A very common feeding mode in brittle stars turns out to be a highly unusual feeding mode in sea stars!

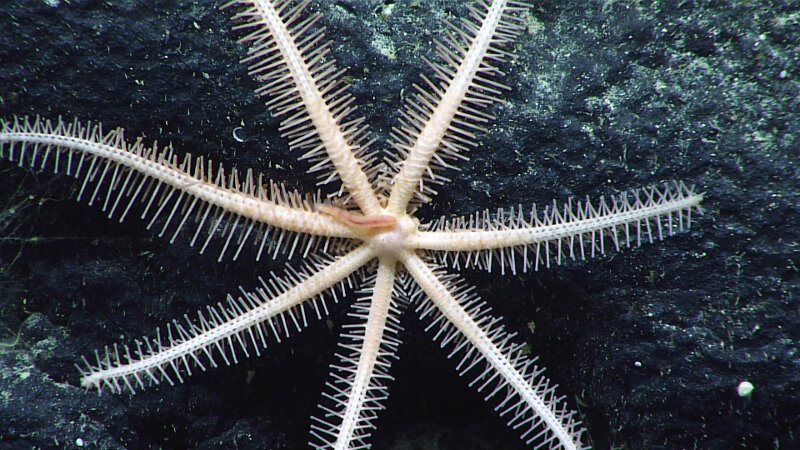

These sea stars have extremely elongated spines along their arms, as seen in this one individual from "Kahalewai" Seamount. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Brisingids are sea stars – proper sea stars – BUT they do something that is VERY odd. They practice an interesting combination of filter feeding AND predation!

These spines are COVERED in tiny claws which act as sort of a "starfish velcro." When the arms are passively extended into the water, they CAPTURE and snag small crustaceans and other food, such as amphipods. As they get caught, prey animals are unable to escape. Food is then moved via the tube feet down to the mouth.

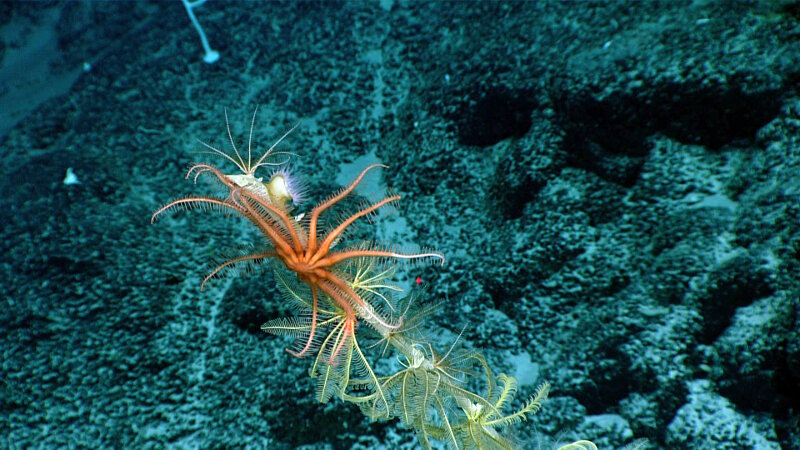

Brisingid at "Kahalewai" seamount, Dive 04 of the Mountains in the Deep expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Brisingid sea stars are so heavily adapted to this life mode that their skeletons are modified for it. The disk, for example, is composed of individual pieces that are fused together for support. The arms "imitate" the shape of other filter feeding echinoderms such as crinoids and brittle stars.

Because brisingids and feather stars (crinoids) often take advantage of similar habitats (i.e., water currents), you often encounter them at the same place.

Brittle stars (aka ophiuroids) are similar to brittle stars.

Sponges process water current to feed and often have sharp and unpleasant structural elements, which make them ideal perches since predators avoid them.

Hundreds of brittle stars occupy a very yellow glass sponge. These animals are perched in areas where water flow is the most conducive to capturing food via water currents with their tube feet and spines. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 404 KB).

On "Kahalewai" Seamount, hundreds of brittle stars occupy a yellow glass sponge. They are perching in areas where water flow is most conducive to capturing prey with their tube feet and spines. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

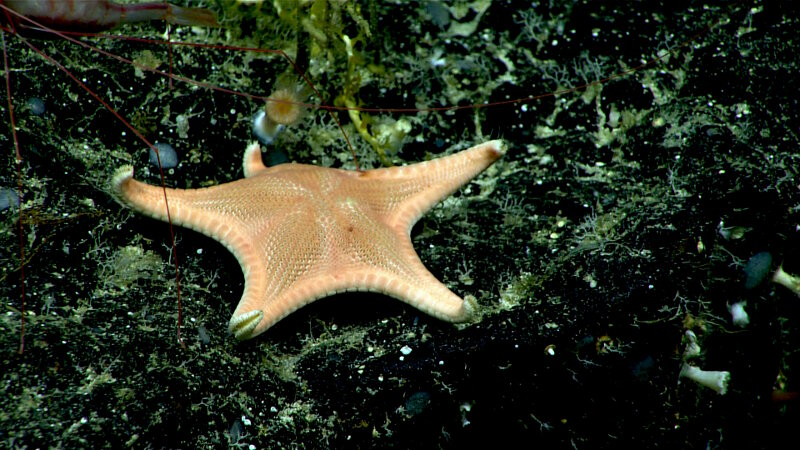

A goniasterid sea star, possibly Mediaster sp., at 875 meters (2,870 feet) on "Whaley" Seamount. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Mountains in the Deep: Exploring the Central Pacific Basin. Download larger version (jpg, 1.9 MB).

This is kind of a "catch-all" term for many sea stars that display a great deal of flexibility in their feeding habits. This might include anything from encrusting animals (e.g., hydroids), to feeding on a large, dead food carcass (e.g, fish, sponges, etc.), or even predation on small animals such as corals or sponges.

Deep-sea sea stars and brittle stars have evolved a dazzling array of feeding behaviors, ranging from surprisingly agile predation to filter feeding to more conventional scavenging. That – in conjunction with their unusual body forms, evolutionary solutions to survival, and their important ecological roles – make these star-shaped echinoderms, as Invertebrate Zoologist Libbie Hymans once said, a "noble group especially designed to puzzle the zoologist."