By Bruce C. Mundy - NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center

May 5, 2017

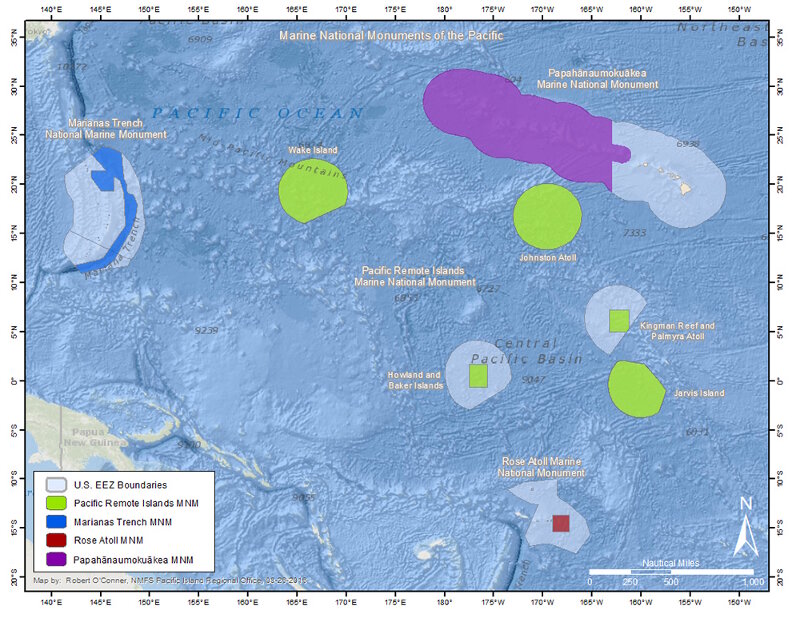

Pacific marine national monuments, along with U.S. Pacific Islands and associated Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). Image courtesy of NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service. Download larger version (jpg, 663 KB).

This NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer survey from American Samoa through the Line Islands is of particular interest for me. Several years ago, I was a member of the first exploration by manned submersibles of Jarvis Island, Palmyra Atoll, and Kingman Reef, the U.S. possessions in that region. Other explorers on those dives in 2005 were Frank Parrish of the NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center (where I also work), Jim Maragos of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Barbara Moore of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research.

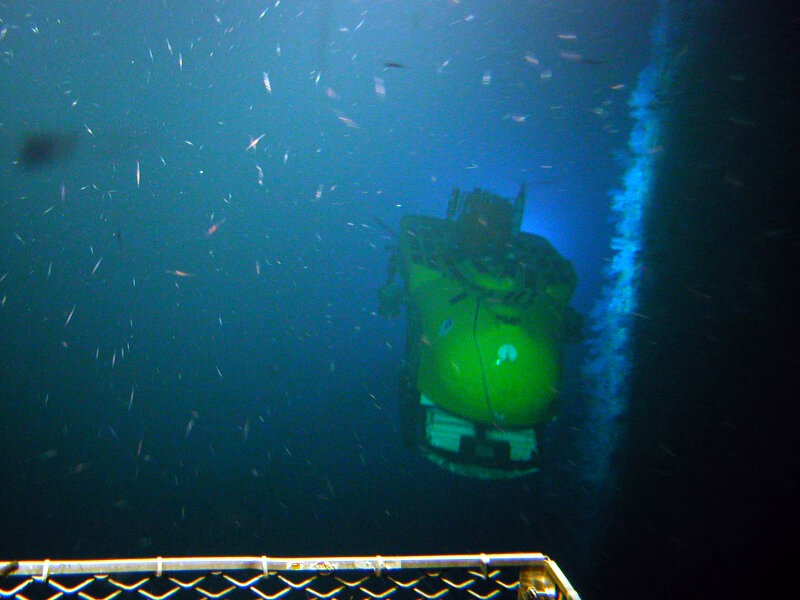

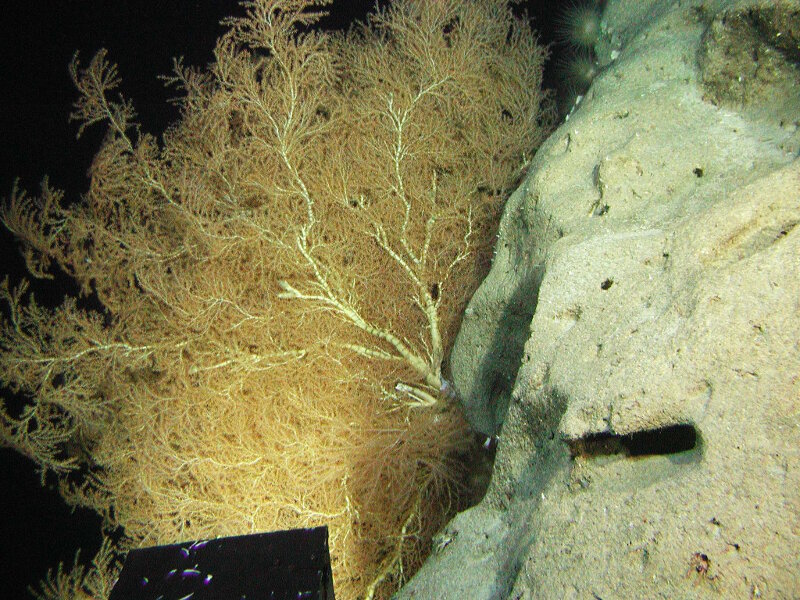

The slopes of Jarvis Island, Palmyra Atoll, and Kingman Reef were first surveyed in 2005 by the University of Hawaiʻi and NOAA's Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory's Pisces IV and V submersibles. Here, one of the Pisces submersibles rests in a notch between two pinnacles, next to a large gold coral fan. The terrain on the slopes of these islands was extremely rugged, posing challenges for the submersible pilots. We expect to see similar topography during NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer surveys at these islands. Photograph by Terry Kerby or Max Cremer, courtesy of the Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

During five dives, we looked mostly between 250 and 750 meters (820 - 2,460 feet). However, on one dive, we went down to 1,000 meters (3,280 feet). Some of the things we saw had never been found in the central Pacific before. Those new things make me very curious about what we will see in even deeper water during this expedition.

In 2005, we explored using the University of Hawaiʻi and NOAA's Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory's Pisces IV and V submersibles. Terry Kerby and Max Cremer expertly piloted the submersibles during the dives.

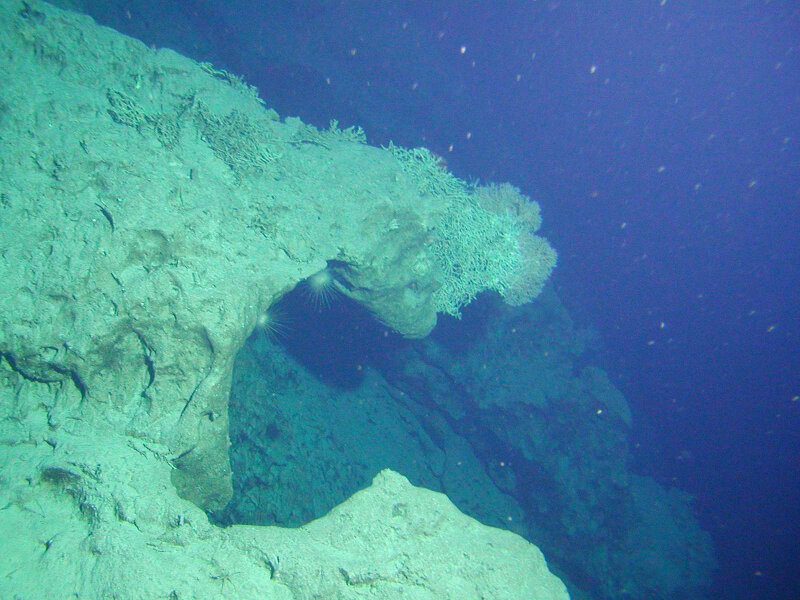

We found very intimidating underwater terrain at the sites we explored. Jarvis Island had sheer cliffs with strong currents that swept past ridges extending outward. Large numbers of small plankton and micronektonic fishes and crustaceans swam or floated past in the water at those locations. Most of the other sites in our five dives had dramatic box canyons alternating with ridges and rock domes. Some sites had overhanging ledges and strange rock formations that resembled the fang-like stalactites of caves.

A Pisces submersible moves along the sheer cliff-face at Jarvis Island, as photographed by the other Pisces submersible. Extraordinarily abundant plankton and micronekton swarmed off of ridges of the cliff where strong currents swept by. Dense lines of deepwater coral fans, to the right of the submersible, also occurred at these ridges. Photograph by Terry Kerby or Max Cremer, courtesy of the Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

The submerged, eroded, ancient reef of these islands had an intimidating topography at many sites – with overhanging ledges, box canyons, ridges, huge domes. Photograph by Terry Kerby or Max Cremer, courtesy of the Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 901 KB).

I was used to seeing certain types of fishes in the Hawaiian Islands, where I had done my previous deep-sea submersible exploration work. What I saw in the Line Islands was very different. Deepwater corals were more abundant at the current-swept ridges of the Line Islands than in the Hawaiian Islands. Those included precious gold corals, which are used in making jewelry, and large bamboo coral fans. However, I am not a coral biologist and knew little about the corals we saw. We also observed large numbers of sea urchins and other invertebrates on our Line Islands dives that looked very different than what we were used to seeing in Hawaiʻi.

Large coral fans, like this bamboo coral were abundant on current-swept ridges in deep waters of the Line Islands. Their high densities were probably due to the high productivity of the waters near the sea surface in this region caused by upwelling of nutrient-rich waters, creating the rain of food from the surface that is carried in the deeper currents of the region. Photograph by Terry Kerby or Max Cremer, courtesy of the Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 2.2 MB).

I am a fish biologist, so I knew more about unusual observations of those animals during our dives. We expected to see the dominant deepwater fishes, such as snappers (Lutjanidae) and groupers (Epinephelidae), which are targets of important commercial fisheries in Hawaiʻi. However, we saw only a few of those in the Line Islands, and fewer species than in Hawaiʻi, which surprised me.

Thousands of small deepwater scorpionfish (Setarches guentheri) were seen resting on sediments of low-gradient slopes or the tops of rock domes in the U.S. Line Islands. This abundance of scorpionfish was not found in the Hawaiian Islands. When we first approached these areas and saw the small, dark spots on the slopes, we thought they were holes. To our surprise, a closer look showed them to be small fish. Photograph by Terry Kerby or Max Cremer, courtesy of the Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 802 KB).

We saw many deepwater cardinalfishes (Epigonidae), just as we did in Hawaiʻi’, but slopefishes (Symphysanodontidae), which are highly abundant in Hawaiʼi, were not seen at all in the Line Islands. Instead, we saw thousands of small scorpionfish resting on the lower-gradient slopes and rock domes. These appeared to be juvenile deepwater scorpionfish (Setarches guentheri), a species thought to rest on the bottom during the day and move into the water at night to feed on plankton. That observation was very different from anything seen during dives in the Hawaiian Islands.

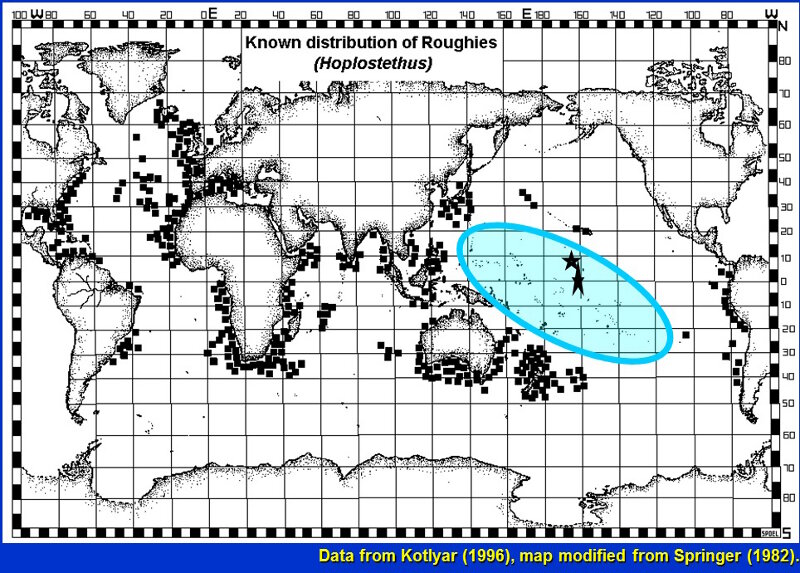

This map shows the distribution of roughies as known in 1996 with small squares. The blue oval shows the vast area of the central Pacific where roughies were unknown. The two stars show the areas of our observations of roughies; the elongate star also includes a site where a pelagic larva had been collected but reported by a different scientific name. Image courtesy of the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service. Download larger version (jpg, 397 KB).

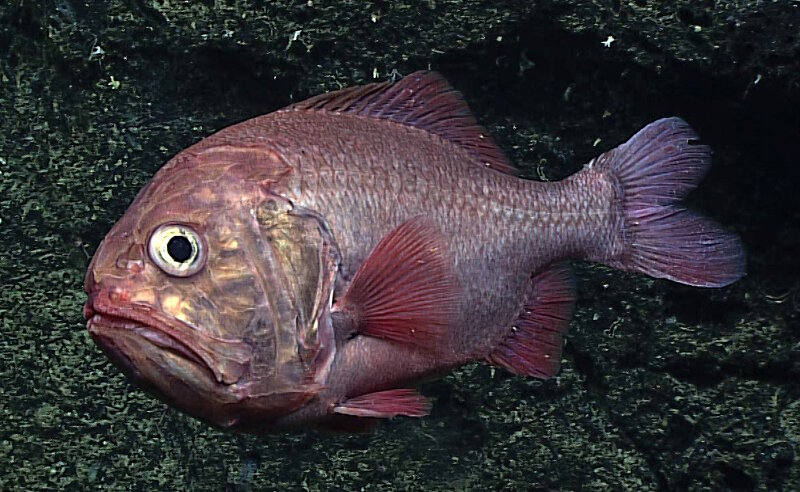

Since the 2005 exploration in the Line Islands, roughies have been seen at seamounts near Johnston Atoll, the Mariana Islands, American Samoa, Tokelau, and the Phoenix Islands during NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer expeditions. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Discovering the Deep: Exploring Remote Pacific MPAs. Download larger version (jpg, 727 KB).

The other striking thing that we found were types of fishes never before recorded from the central Pacific Islands. Roughies (Hoplostethus species), related to the once commercially fished orange roughy, were the eighth most abundant type of fish we saw. Yet, roughies were not reported from the region before, with the exception of one larva that had been described as a different genus in a different family. Roughies have since been found to be abundant at depths between 300 to 700 meters (1,000 - 2,300 feet) at almost all central Pacific locations explored by NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer.

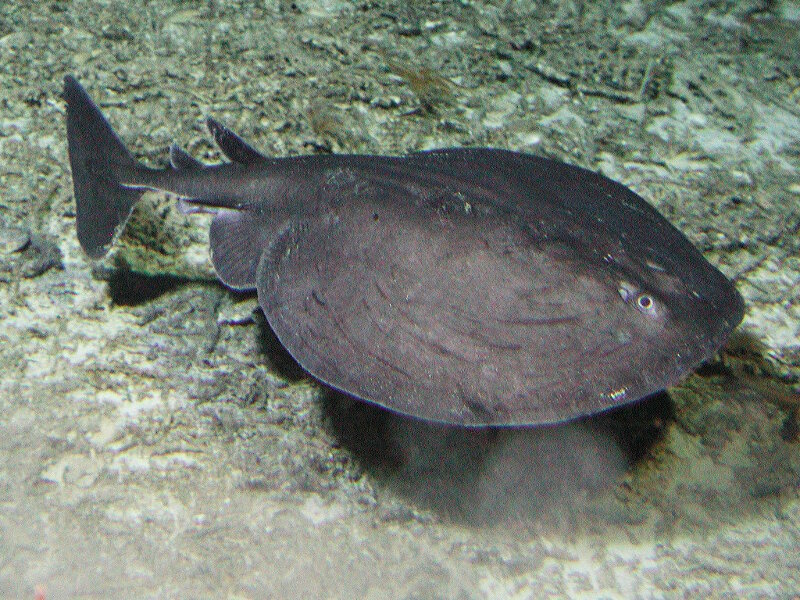

Torpedo ray seen during submersible surveys in 2005 at the U.S. Line Islands. This fish has not been seen again since. Photograph by Terry Kerby or Max Cremer, courtesy of the Hawaiʻi Undersea Research Laboratory. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

Other newly discovered fish species for the central Pacific included a torpedo ray (Torpedo species) at Jarvis Island and oreo dories (Neocyttus species), which are very similar to a species described from the Seychelle Islands in the western Indian Ocean. The oreo dories were seen in abundance again during the NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer expedition at seamounts in the Tokelau and Phoenix Islands areas. Their family, Oreosomatidae, had never been found in the tropical Pacific before.

One of the biggest mysteries is an unidentified green eel with a black stripe that resembles a species, Myroconger seychellensis, also described from the western Indian Ocean. If the identification of that eel is correct, that is another fish family previously unknown from the central Pacific. Again, this type of eel was seen during remotely operated vehicle (ROV) exploration with NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer at other central Pacific areas in the past couple of years.

The oreo dory, first seen during 2005 exploration in the Line Islands, and seen again during NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer ROV surveys at other central Pacific locations. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Discovering the Deep: Exploring Remote Pacific MPAs. Download larger version (jpg, 565 KB).

Striped eel, first seen in 2005 and later seen during a 2017 Okeanos Explorer dive within the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, now known as Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Discovering the Deep: Exploring Remote Pacific MPAs. Download larger version (jpg, 785 KB).

All of these discoveries, along with the more recent ones from ROV exploration with NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer across the tropical Pacific, make me wonder what new things we will find in this expedition. I am eager to go back to the Line Islands, by telepresence from the Okeanos Explorer, to see what new discoveries wait for us there. With an Internet connection, you can join the expedition to find out, too!