Charles Messing - Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography, Nova Southeastern University

February 18, 2017

Although no crinoid has a brain, the nervous system, which includes central nerve rings and branches to each arm and pinnule, is organized enough so that this featherstar can coordinate the operation of hundreds of little muscle bundles and swim surprisingly fast, and then parachute to safety. Wait for it... Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 American Samoa. Download largest version (mp4, 8.2 MB).

This large stalked crinoid, or sea lily (either Metacrinus or Saracrinus), flexes its feathery arms back into the current. It can release the grasp of its hooks along its stalk, lie down, and crawl with its arms. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 American Samoa. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Sea lilies and feather stars, properly called crinoids (which means lily-like), are among the strangest of creatures that scientists will encounter during the expedition. Although they appear plant-like in many respects, they in fact are animals, complete with a digestive system and a nervous system. Their closest relatives are the sea stars, sea urchins, brittle stars, and sea cucumbers. Together, these animals form the major branch of the animal kingdom called the echinoderms (“spiny-skin”). Echinoderms have a basic five-sided symmetry, calcareous skeleton, and unique internal canal system and ligamentary tissue.

Although crinoids are the least understood of living echinoderms, their skeletal remains are among the most abundant and important of fossils. They arose during the early Paleozoic Era and were so abundant in many places that their skeletal remains produced vast limestone deposits in many places around the world, including the American Midwest. More than 5,000 fossil species have been described to date.

Crinoids have declined in diversity since their peak some 300 million years ago, but they are still enormously abundant in many marine habitats, from shallow coral reefs to the floors of oceanic trenches.

Porphyrocrinus sea lilies attach to hard substrates via a holdfast and have arms that terminate in slender filaments. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 American Samoa. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

We use the informal name “sea lily” for those species that retain a stalk as adults and “feather stars” for those that lose the stalk as small juveniles. However, these are not strict taxonomic groupings. It turns out that the stalk has been repeatedly lost and retained in adults several times. However, in modern seas, although feather stars occur from just below the tide line in some places to great depths, sea lilies no longer occur in shallow water; the shallowest species, Metacrinus rotundus, can be found at a depth of 100 meters off Japan.

All crinoids are suspension feeders, subsisting on the smorgasbord of small plankton and detritus that drifts past their outstretched arms. The fine side branches, or pinnules, that give their arms their feathery appearance are lined with small fingerlike tube feet (the same structures that line the undersides of sea star arms, but without the sucker tips) that flick passing food particles into a groove, where microscopic hairs (cilia) carry them down to the central mouth, conveyor-belt style.

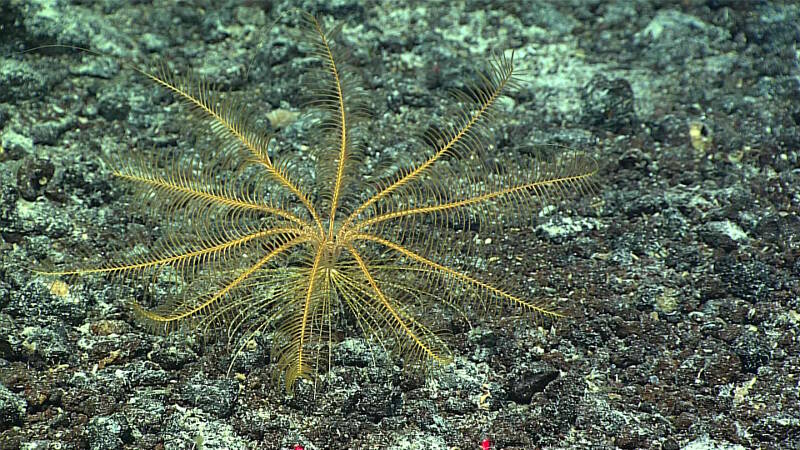

This unusual featherstar, probably Paratelecrinus, also has terminal arm filaments, which may betray a close relationship, discovered via DNA sequencing, with stalked Porphyrocrinus. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2017 American Samoa. Download larger version (jpg, 1.8 MB).

Most of the sea lilies that will probably be observed during this expedition array their arms in a bowl or dish with the arm tips flexed back into the current and the top of the stalk bent so that the central mouth faces away from the current. They use their unique echinoderm ligamentary tissue to lock the arms in place, which does not require expending energy. If the current gets too strong, or the crinoid is disturbed or attacked (some sea urchins feed on crinoids), the ligaments go flaccid, and muscles on the grooved side collapse the arms together for protection.

Although some crinoids are permanently attached to hard substrates by a holdfast at the bottom of the stalk (much like a sea fan or black coral), or anchor in sediment via rootlike structures, the feather stars and some of the sea lilies that have hook-like cirri can release their hold on the seafloor. These species can use their arms to crawl, and some feather stars can even swim.

Scientists have described several hundred crinoid species, but we are always finding more. I won’t be surprised if we find at least one new species during this expedition.