By Christopher Kelley, Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory – University of Hawaii

Scott France, University of Louisiana at Lafayette

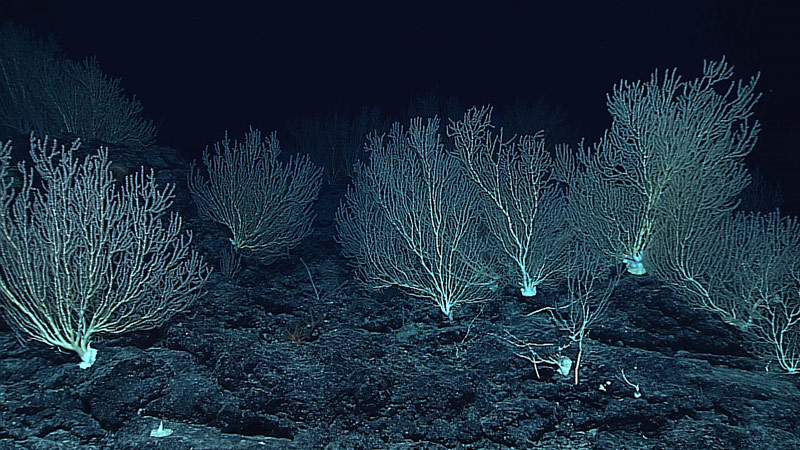

Large bamboo coral colonies on a guyot ridge. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

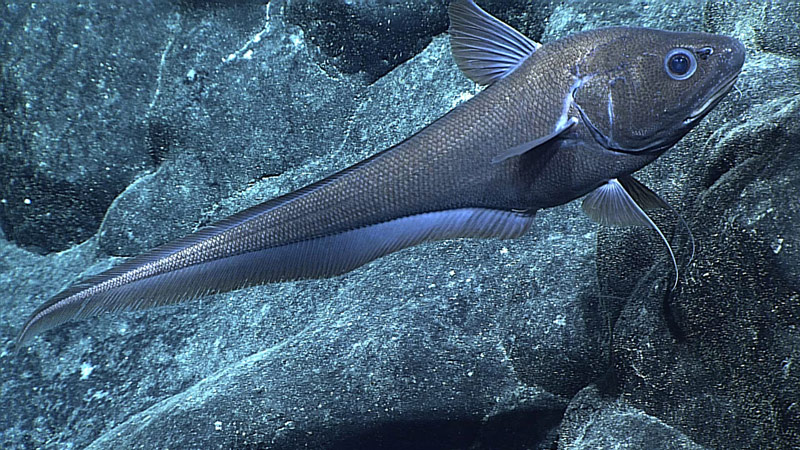

A rat-tail fish that typically prefers calmer waters. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

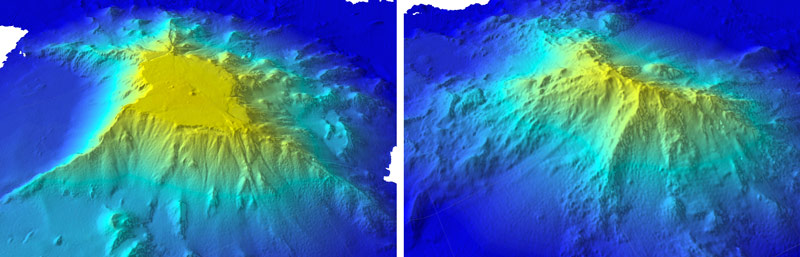

Seamounts are volcanic in origin, and if during their geological life, they never reach the surface, they retain their conical shape, some having craters on top and others without. But seamounts that erupt and grow to reach the surface have their conical tops flattened as a result of both erosion and coral reef growth. When these flat-topped seamounts eventually sink back down to deep water, they are called guyots.

Of all of the seamounts in the Pacific, guyots have the most varied geology and therefore the most varied habitats for animals to live. The base and flanks of a guyot are similar to those found on a conical seamount. Both are made of volcanic rock emerging from the flat, sediment-covered, abyssal seafloor. Like conical seamounts, the base and flanks of a guyot have ridges that may accommodate high-current dwelling filter-feeding corals and sponges, and canyons formed by flank failures that accommodate calmer-water fishes and invertebrates.

The top or summit of a guyot is where it differs significantly from a conical seamount. On a conical seamount, the volcanic rock emerging from the bottom simply continues until it forms a peak or until it falls away into a summit crater created when the underlying magma chamber collapsed. In contrast, guyot summits have a cap of carbonate rock laid down by shallow-water coral and bivalve reefs when the seamount was at the surface many millions of years ago.

Flat-top guyot (left) shown in comparison to a conical seamount (right). Image courtesy of the Schmidt Ocean Institute. Download larger version (jpg, 706 KB).

Reef growth was not continuous back then but rather occurred in pulses, resulting in the formation of terraces that form steps circling the highest part of the summit. These terraces provide short but sharp drop-offs where we believe accelerated currents can support lush communities of corals and sponges. Some types of deepwater fishes may also like to swim along these terrace edges since this can be where small planktonic prey animals living in the water column tend to congregate.

The relatively flat terrain on the uppermost terrace allows sediment to accumulate over time, sometimes to many meters in depth. This thick covering hosts a different suite of animals than are found on the steeper, hard flanks of the guyot: sediment-dwelling shrimps, isopods, crabs, sea stars, brittle stars, sea cucumbers, sea pens, worms of various kinds, and even a few species of sponges. Fishes, including some species of rattails and cusk eels that feed on these animals, can also be found on the summits.

A sediment-dwelling sea cucumber. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

A sediment-dwelling shrimp. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

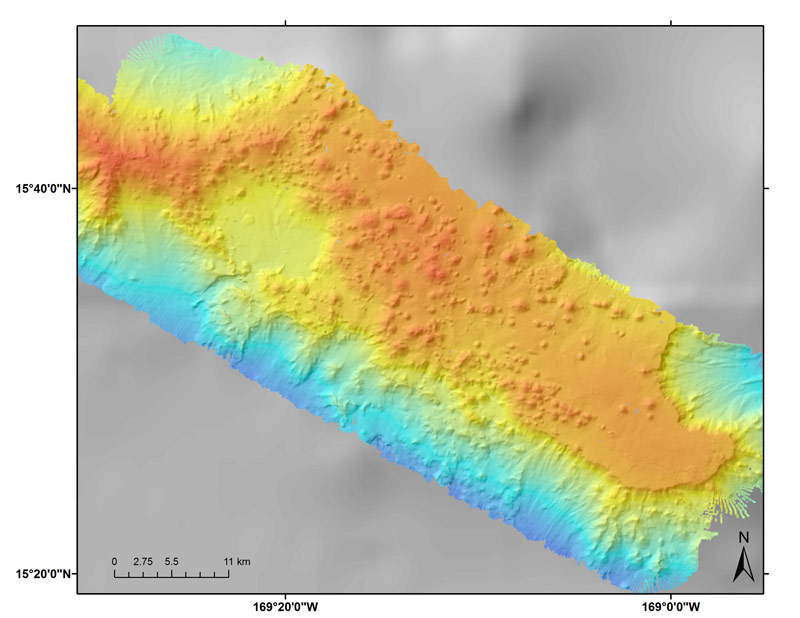

Furthermore, some guyots experience rejuvenated volcanism that creates small cones and craters rising 200-300 meters above the carbonate and thick sediment layers on their summits. These cones function as miniature seamounts that provide elevated meso-scale habitats for corals and sponges that would otherwise not occur on the summits.

Sediment-covered guyot summits – with their terraces and, in some cases, emergent cones – provide a mixture of habitats that are not found on conical seamounts and thus may enhance the diversity of deep-sea animals living on them. Guyots are therefore potentially important to the overall ecology of the deep sea. However, very little is known about guyot communities, so an important objective of this cruise is to learn more about them. Unfortunately, the flat tops that make these seamounts unique also make them the easiest type of seamount to trawl for fish or mine for minerals. We need to quickly learn more about them and the communities they host if we want to have any chance at all of minimizing the impacts of human activities in the deep sea.

Partially mapped guyot showing cones on the summit that resulted from rejuvenated volcanism. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).