By Scott C. France - University of Louisiana at Lafayette

September 27, 2015

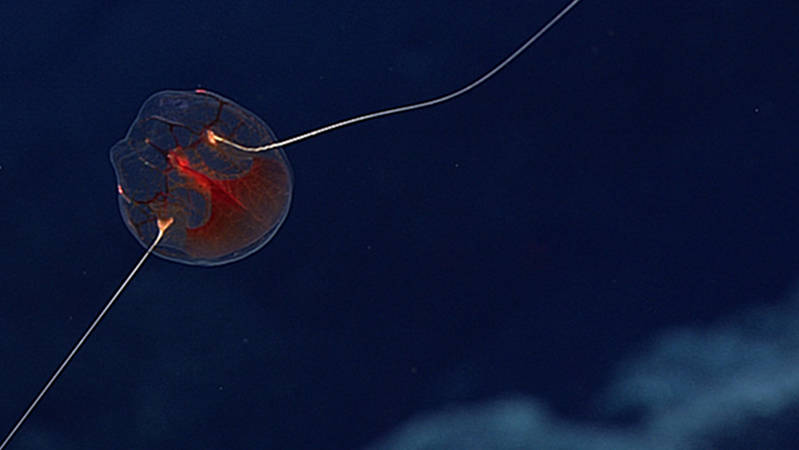

A ctenophore with long tentacles belonging to the Family Aulacoctenidae was documented not far off the bottom at Southernmost Cone. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 1.1 MB).

We may be working in the tropics, but it may come as a real surprise to some that down on the deep-sea floor, the bottom waters we are exploring are near freezing temperatures. As an example, on our dive on Hutchinson Seamount, the surface water temperature was 29.6°C (85.6°F) when we deployed the Deep Discoverer remotely operated vehicle (ROV). When we arrived on bottom at 1,700 meters, the in situ temperature had decreased to a near-freezing 2.6°C (36.7°F).

This sea toad (Chaunocops cf. melanostomus) was spotted during our dive at Southernmost Cone. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Our planet is heated by solar radiation, incoming energy from the sun. In the ocean, this energy is rapidly absorbed or reflected in the upper surface, leaving little energy to penetrate deeper, and so deeper water is not heated (this also explains the lack of light!). There are also physical factors at play: warm water is less dense than cold water, and so cold water will sink while warm water floats above it. Mark Denny refers to “the two-layered ocean,” where the upper layer is warmer and less dense and does not easily mix with the deeper cold water.

Deep-sea corals provide habitat for a variety of organisms. Here a brittle star has taken up residence on an octocoral (pink) that is being overgrown by a zooanthid (yellow). Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

The physical properties of temperature’s affects on density is responsible for one of the major movements of water through the ocean, the so-called “ocean conveyer belt.” This process describes a global-wide circulation from shallow waters near the Earth’s poles, into the deep ocean, and up to the surface again in the North Pacific: essentially an overturning of the global ocean, but one that takes as much as 2,000 years to complete.

Because the Earth is round, the angle of the surface relative to the incoming radiation differs with latitude, so at high latitudes the oceans receive less sunlight – the poles receive only 40 percent of the heat that the equator does. Thus, the surface waters in the Arctic and Antarctic are not warmed much, in fact they are very cold. So cold, in fact, that at times that the surface water freezes to form ice.

Ice is a solid phase of fresh water, so the salts that were in the seawater are “squeezed” out into the unfrozen water. This makes that seawater even saltier, and the higher the salinity (a measure of the salt concentration), the more dense the water! So this very cold, salty water sinks into the deep ocean, and once it gets there, it begins to spread across the ocean floor. In fact, in the deep ocean south of Hawaii, we can detect cold salty water flowing across the seafloor from around Antarctica.

Scott France and Mackenzie Gerringer in the control room onboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 3.2 MB).

Interestingly enough, working in the ROV control room on the Okeanos Explorer during a dive can be downright chilly as well. During one dive, the temperature in the control van dropped at one point to 18.3°C (65°F); perhaps not the abyssal cold experienced by the animals on the seafloor below us, but plenty chilly when sitting for hours at a control station. Just beyond the door, out on the deck, the tropical air temperature was 29.1°C (84.4°F).

The control room is a relatively small space with 47 monitors, multiple racks of electronic equipment accessing 35 computers (plus multiple laptops), and usually seven or eight people working, all generating heat. The chilly interior temperature that is maintained is needed to protect from overheating the many electronics being used to obtain and broadcast the dive imagery.

After a dive we are always rewarded with a step into the warm tropical air. A little shivering is a small price to pay for the thrilling experience of exploring our unknown ocean depths – as illustrated through some of the images below.

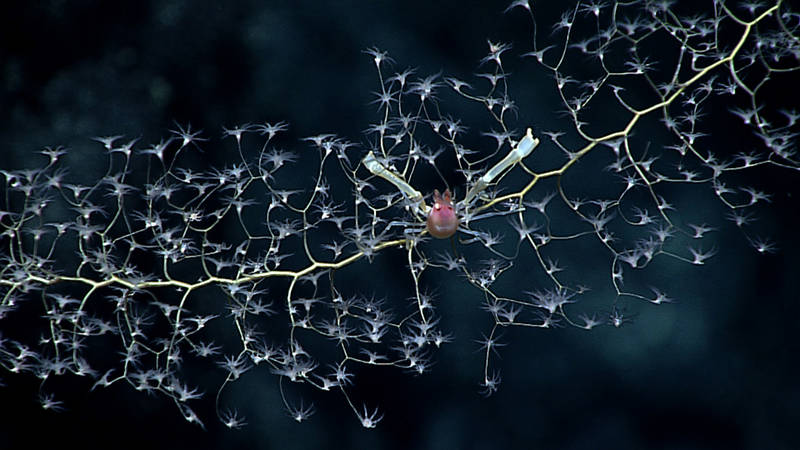

Squat lobsters are common associates on deep sea corals, like this one observed at Guyot Ridge. Oftentimes a crab species will only associate with a certain type of coral. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

A chimera observed at Deep Twin Ridge. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 921 KB).

If you look closely you can see the intestinal track of this sea cucumber. Here it is using its adapted feet to bring food-filled sediment to its mouth. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 908 KB).

An unusual polychaete documented during our dive at Deep Twin Ridge. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 677 KB).

ROV Deep Discoverer (D2) images a stalked sponge. In the background, you can see a number of deep-sea corals and sponges at the edge of D2’s light pool. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 574 KB).