By Bruce Mundy - Fishery Biologist, NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center

August 31, 2015

We saw this this goosefish or anglerfish of the genus Sladenia at Swordfish Seamount in the Geologist Seamount group during Dive 05 during Leg 3 of the expedition. Researchers aboard the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory’s submersibles also found Sladenia at the active undersea volcano Loihi, located south of Hawaii Island–an area that thousands of years from now will emerge from the ocean to become the next island of the Hawaiian Archipelago. Scientists previously identified these fish as Sladenia remiger, a species described from Indonesia. However, the recent description of another species, S. zhui, from the western Pacific indicates that the identity of the species in Hawaiian waters needs reevaluation and further study. Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download (mp4, 17 MB)

Volcanoes created all of the seamounts and islands in the central Pacific Ocean. The coral reefs that we see now extend up into the sunlit shallow water, but are established on foundations of ancient, extinct volcanoes. The carbonate rock created by the reefs in the shallows does not extend to the deeper waters of most of the Okeanos Explorer dives. At these depths, we only see the lava flows from ancient, and not so ancient, volcanoes. Recent lava flows– like those explored during Dive 03 of Leg 3 of the Hohonu Moana Expedition – can be found at Hawaiʼi Island. A few of the ancient seamounts are even as old as the age of the dinosaurs (although the dinosaurs were never able to cross the Pacific Ocean to get to these Pacific islands and seamounts).

The fishes that we see on all but the shallowest Okeanos Explorer dives live in the habitats of these extinct volcanic lava flows – they are volcano fish. Some live near active volcanoes as well as on extinct features.

The armored searobin, Scalicus engyceros, was one of the fishes David Starr Jordan reported among the specimens floating offshore of a 1919 lava flow from Mauna Loa. We photographed this individual during the August 29, 2015, Okeanos Explorer remotely operated vehicle dive off Keahole Point, several miles north of the 1919 lava flow on the Kona Coast of Hawaii Island. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 470 KB).

A few of the fish species that we saw in the Hohonu Moana Expedition were originally discovered from specimens found floating at the ocean surface – they lived in deep waters but were killed by lava flowing into the sea from eruptions of Mauna Loa volcano on Hawaiʼi Island. The famous ichthyologist David Starr Jordan, the original president of Stanford University, described that phenomenon for the first time in 1921. Most of the fishes that he reported had been described by others in earlier years, so many of the new names that Jordan coined for the species are no longer used. One that he mentioned, but did not describe as a new species, was later named for the volcano – the longtail slopefish Symphysanodon maunaloae.

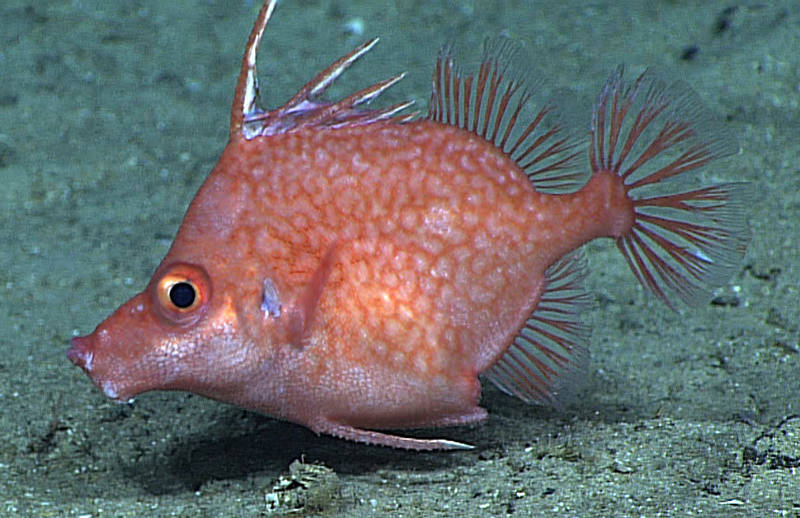

The Hawaiian spikefish, Hollardia goslinei, was first discovered as a specimen that floated to the surface because of lava from the 1950 eruption of Mauna Loa that flowed into the ocean on the Kona Coast of Hawaiʼi Island. Scientists on Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory submersible dives often saw spikefish at 902–1690 feet (275–515 meters) throughout the Hawaiian Islands and at Johnston Atoll. This spikefish, or a very similar species, was also commonly seen in dives in the Line Islands south of Hawaii. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 785 KB).

In June 1950, another lava flow from Mauna Loa killed deep-sea fish, many of which were previously unknown. One of those killed was the strange Hawaiian spikefish, Hollardia goslinei, which has since been found to be very abundant. In fact, the Okeanos Explorer dives found a number of spikefish during the shallowest surveys off Oʼahu and Hawai`i Island.

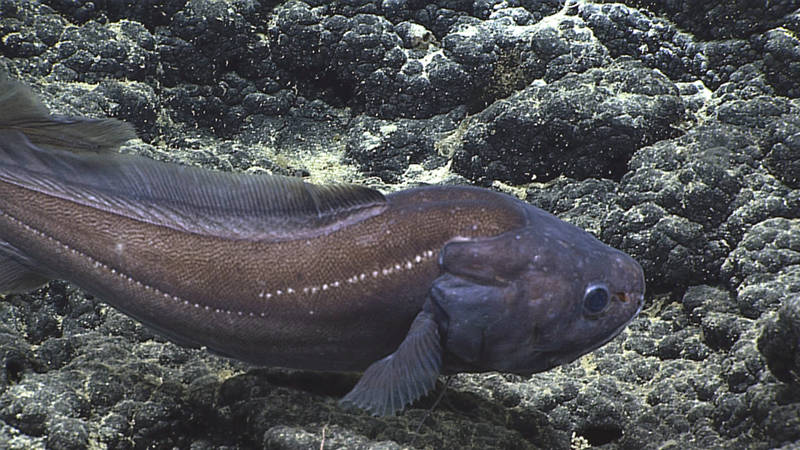

ROV Deep Discoverer filmed this Diplacanthopoma species between (1,096 and 1,380 meters (3,596 and 4,528 feet) on Bank 9, about 50 nautical miles south of Pearl and Hermes Atoll in the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. The two-part lateral-line (white dots on the body), the absence of scales on the head, and the flap above the gill cover are characteristics of the genus. Though this individual had the color of the specimen that Gosline identified as Diplacanthopoma riversandersoni, that identification will need to be reevaluated if Hawaiian specimens of Diplacanthopoma are collected. Ichthyologists need to review and determine the number of species in the genus, as well as their geographic distributions, before we can get accurate identifications. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

For me, some of the most interesting discoveries in the Okeanos Expedition were cusk eels of the genus Diplacanthopoma, for the reasons described below.

Researchers discovered two species of Diplocanthopoma floating offshore of the 1950 Mauna Loa lava flow at Hoʼokena on the Kona coast. Dr. William Gosline the ichthyologist at the University of Hawaiʼi at the time, identified one of the species as Diplacanthopoma riversandersoni, which was first described in 1895 from the Arabian Sea; however, he was unable to name the second species. Diplacanthopoma species are livebearing fish in the family Bythitidae.

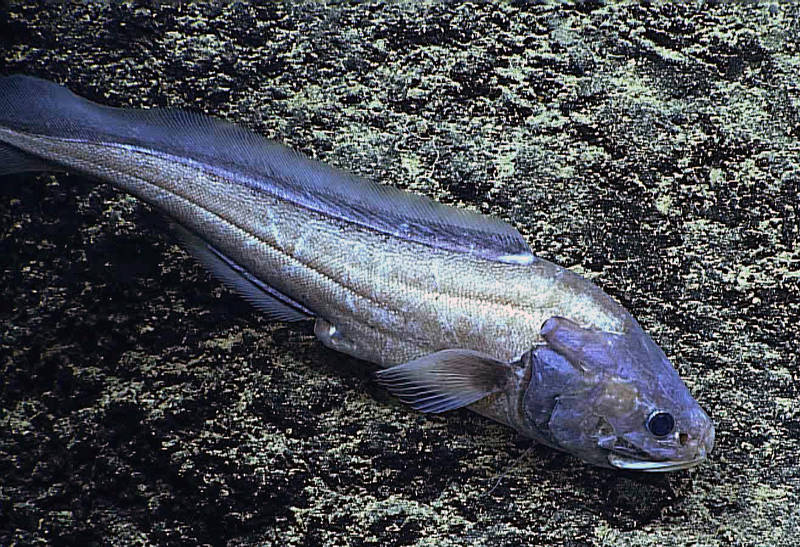

During the Hohonu Moana Expedition, we have observed two types of Diplacanthopoma, but we don’t know yet if those match the species described Gosline described.

The Hawaiian Diplacanthopoma had never before been seen alive, and we knew nothing about their ecology. Now we know something about their habitat, including that they live in very deep water of at least at 1,096-1,380 meters (3,596-4,528 feet). What’s more, we now know that they are found not only off Hawaiʼi Island at the southern end of the Hawaiian Archipelago, but also northwestward almost to the other end of the island chain, as well as at the Geologist Seamounts located west of Hawaiʻi Island.

A second Diplacanthopoma individual with a different color, filmed by ROV Deep Discoverer at Ellis Seamount to the west of Hawaiʼi Island on September 2, 2015. We do not know if this is a second, separate species or a color variant of the same species observed at Bank 9. Gosline did not describe the color of the second, unidentified species that he found off the 1950 Kona Coast lava flow. More research is needed to identify these species. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Diplacanthopoma species in other parts of the world occur to depths of 1,640 meters (5,380 feet); those seen by ROV Deep Discoverer were living at the deep end of the known depth-range for the genus. This fact gives us a puzzle to solve; how did lava flows from the high volcano of Mauna Loa kill fishes living so deep?

Perhaps these species also occur in shallower water, like many of the other species found floating off of the Hawaiʻi Island lava flows. Or perhaps the lava flows and their other effects reach deeper depths than we realize.

In 1920, David Starr Jordan published this description of the early lava flow by Carl Carlsmith:

At the end of September, 1919, a lava flow started in the district of Kau on the island of Hawaii, and flowed to the sea through the land of Alika, which name was given to the flow to distinguish it from others. The lava was of a very fluid variety, and upon reaching the sea it built a tunnel for itself upon the floor of the ocean. The offshore water at this point is very deep, and within a hundred feet or more of the shore reaches a depth of at least 200 fathoms. On visiting the place in a native canoe on the night of October 1, I found that the subterranean tunnel was bursting at various points with heavy detonations and sending up thick clouds of steam. These clouds of steam were noticed by me as far as 2 miles from the point where the flow entered the ocean.1

In 1954, William Gosline and others wrote a similar account, adding:

Whenever a heavy surge of lava hit the sea, a large amount of steam rose from the surface. Between the peaks of the surges, at least during the later stages of the flow, the moving column of lava entered the sea quietly, unexpectedly resembling an escalator disappearing through the floor of a department store. Apparently the failure to cause surface steam at such times was due to the cooling and hardening of the outer layer of the lava column into a water-impervious shell through which the rest of the lava flowed. (Such conduits, now hollow and sometimes extending for distances of more than a mile, are well-known features of the Hawaiian terrestrial landscape.) Since the molten material flowed continuously without ever filling this shell, it can be assumed that the lava was breaking out somewhere below. Such outbreaks presumably produced steam explosions which could be felt even in a skiff anywhere near the flow. However, no steam from these assumed outbreaks ever reached the surface, nor was this to be expected unless they had been very large or very near the surface.2

They quoted others who said that a line of steaming water extended to sea for about half a mile from the place where the lava entered the ocean, which is over very deep water at Hawaiʻi Island. They suggested that the fishes might have been killed by direct effects of the lava, such as overheating or lethal chemicals in the flows. They also suggested that the fish might have been killed by indirect effects, such as being carried upward in vertical currents created by the hot lava or by the underwater volcanic explosions from the lava flow.

One thing is clear, it is better to be a volcano fish on an extinct volcano than on an active one.

1W. A. Gosline, V. E. Brock, H. L. Moore, and Y. Yamaguchi. 1954. Fishes killed by the 1950 eruption of Mauna Loa. I. the origin and nature of the collections. Pacific Science, vol. 8, page 23.

2D. S. Jordan. 1920. Description of deep-sea fishes from the coast of Hawaii, killed by a lava flow from Mauna Loa. Proceedings of the U.S. National Museum, volume 59, number 2392, page 643.