By Dr. Christopher Mah - Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

August 15, 2015

The goniasterid sea star, Calliaster pedicellaris, feeding on a bamboo coral. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 213 KB).

My name is Dr. Christopher Mah. I am a research collaborator in the Invertebrate Zoology Department at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. I am one of the world’s experts in the biodiversity and evolution of sea stars (also called starfishes or asteroids).

Since 2012, I have been one of the shore-based experts assisting the scientists aboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer, providing identifications (i.e., species names) and expertise in the biology of species encountered during the expedition.

A brisingid asteroid, probably in the genus Hymenodiscus. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 302 KB).

Probably one of the most exciting aspects of these expeditions is being able to observe very poorly known, or sometimes new, species alive and in their own habitat! Before the advent of submersibles, most species were collected via trawl net and as a consequence, specimens of animals were often badly damaged during collection and documented out of context. What did they eat? How did they live? Are they predators? Scavengers? Many deep-sea animals have unusual body shapes with bizarre structures, which are VERY different from their shallow-water representatives and so, until they are seen alive, we have no idea how they live.

Brisingid sea stars for example, are filter feeding sea stars, which hold their arms up into the water in order to feed on tiny crustaceans in the water currents. Prior to submersible observations of this species in the mid 1970s, it was thought that they dragged their arms along the bottom to feed on detritus or other prey!

Okeanos Explorer has made exciting new discoveries of predation by sea stars on sponges and deep-sea corals in the Hawaiian region. At the time of writing this weblog, I can count at least three new discoveries of predation on sponges and just as many observations of predation on Hawaiian corals.

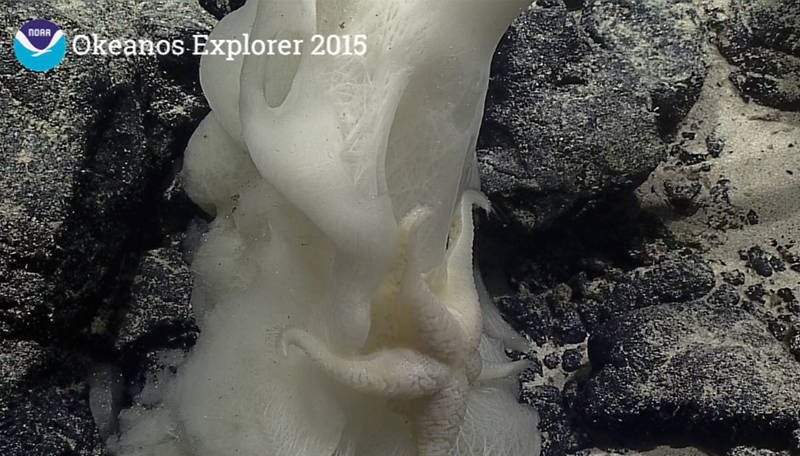

The rarely encountered sea star Pythonaster sp. (Myxasteridae). A first record for Hawaii and possibly a new species, observed feeding on a glass sponge. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 340 KB).

One observation of the sea star Pythonaster sp. was also exciting because it was a very rarely encountered species that was poorly known to scientists, with fewer than 10 specimens known in museums worldwide! From one observation we discovered a new record of this species in the Hawaiian Islands, and with that same observation, we now know more about its biology than has been known since its initial discovery in 1885.

Understanding predation in these ecosystems is important. Many sea stars in shallow habitats are argued to be "keystone species.” These are species which can significantly affect the structure of the ecological community by feeding on specific types of prey. Sometimes the species or even the size of the prey that the seastars feed upon is important to maintaining a healthy ecosystem.

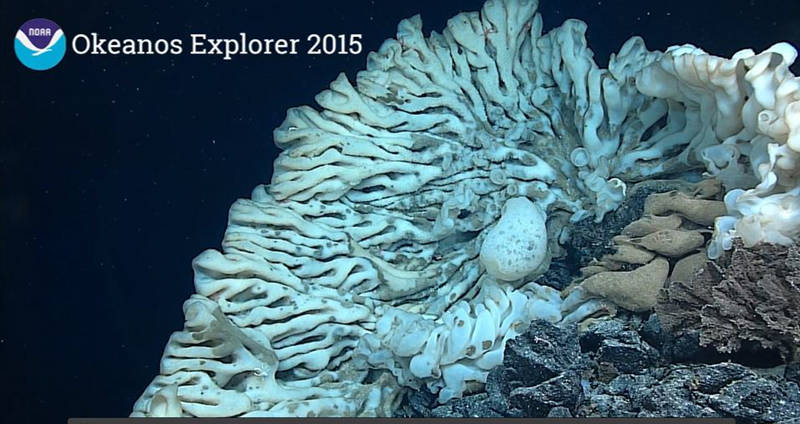

Observations such as these are doubly important towards understanding the role of sponges as ecosystem engineers. During the discovery of the giant 3.5-meter long (11 feet!) glass sponge the other day, we observed numerous brittle stars, squat lobsters, and one sea star, which was feeding on it. These sponges form habitats for other organisms in a manner similar to the way shallow-reef corals do for shallow-water fishes, invertebrates, and other tropical organisms.

Possibly the largest sponge ever recorded, seen August 12, 2015. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, 2015 Hohonu Moana. Download larger version (jpg, 283 KB).