By Jason Chaytor, Amanda Demopoulos, Uri Ten Brink, and Andrea Quattrini - U.S. Geological Survey

Mike Cheadle - University of Wyoming

April 16, 2015

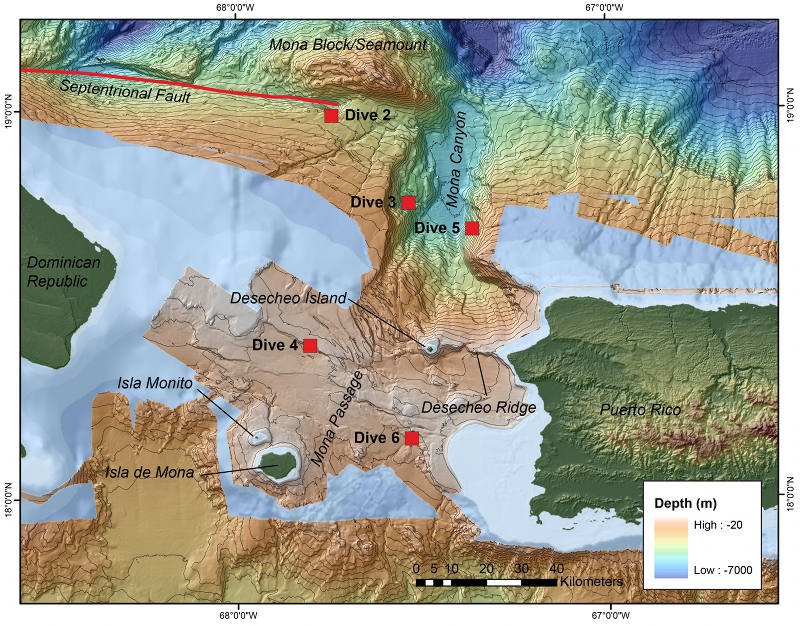

Overview of Okeanos dives the Mona Passage region. The long red line highlights the area of the Septentrional Fault. Image courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey. Download larger version (jpg, 4.1 MB).

The Mona Passage region encompasses the area between Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, from the Puerto Rico Trench to the Muertos Trough. It includes Mona Canyon, Mona Seamount/Block, and the Mona Passage.

The complex seafloor morphology of the region is the result of a mix of oceanographic and tectonic forces that are actively forming and reshaping the landscape. However, the seafloor features remain largely unseen by human eyes. The degree to which this complex topography and the associated oceanographic environment influence the biodiversity and community ecology of this region is unknown.

Eastern Hispaniola (the Dominican Republic), Mona Passage region, the Island of Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands form the eastern end of the Great Antilles at the boundary between the converging Caribbean and North American tectonic plates. This remnant of an intra-oceanic arc formed in the Cretaceous-early Paleogene period (approximately 50 to 120 million years ago). The North American and Caribbean plates continue to interact, leading to the formation of the major geologic features in the Mona Passage region that were visited in Dives 2 through 6 of Océano Profundo 2015: the Septentrional Fault, Mona Canyon, and the floor of Mona Passage.

Dives conducted along the east and west walls of Mona Canyon, which is believed to be a major geologic rift separating different parts of the original volcanic island arc, provided a window into the region’s geologic past by traversing up exposures of rocks that recorded the long and dynamic history.

On the east wall of the canyon, outcrops of breccia and conglomerate resemble rocks found along Desecheo Ridge during remotely operated vehicle (ROV) dives in 2013. These outcrops are most likely related to the volcanic construction of the region.

Outcrops of breccia and conglomerate along the east wall of Mona Canyon. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Overall, the angular blocks were relatively devoid of sessile fauna. Benthic organisms found attached to the rocks included arborescent forams; several species of sponges, including demospongiae and hexactinellids; black corals, including whip and branched morphologies; and soft corals. A few unknown bamboo corals were observed, with their large polyps oriented upwards, helping trap food particles fluxing through the water column.

This sea star, Laetmaster spectabilis, has not been recorded since it was initially described 130 years ago. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Holothurians were observed on the sedimented slope and on the lightly sediment-draped rocks along the canyon wall. A few fish (cusk eels) and crustaceans (shrimp, galatheid squat lobsters) were also observed. Asteroid seastars included brisingids found on the tops and sides of the rocks. Additionally, a six-rayed seastar (Laetmaster spectabilis) was imaged that had not been recorded, collected, or observed since the type specimen was collected 130 years ago.

Climbing the west wall of the canyon from approximately 3,800 meters, the ROVs encountered the younger carbonate platform sequence of rocks (limestone and other sedimentary rocks), present at a deeper depth than expected, possibly due to the action of a large, ancient submarine landslide.

During our dive along the west wall of Mona Canyon, we encountered a younger carbonate platform sequence of rocks. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 2.6 MB).

The sedimented slope that was present at the start of the dive was a trap for plant and macroalgal detritus and various pieces of trash. The slope was populated by holothurians and their biogenic traces were evident on the soft sediment surface. Sea pens (Umbellula) were found rooted within the soft sediments, while other corals encountered were directly attached to the rocks. These corals included antipatharians (Stichopathes, Bathypathes, or Schizopathes) and bamboo corals with large polyps, similar to the bamboo corals observed on the east wall. Sponges, including carnivorous forms, were found on the rocks located upslope, some with associated polychaetes. The rocks also were populated by anemones and sponges. Seastars observed included brisingids and a pterasterid. Predatory tunicates housing commensal polychaetes were also found attached to rocks.

Invertebrates swimming within the water column close to the sea floor included black ctenophores (cydippids), holothurians, and cirrate octopods (Cirrothauma murrahi).

Fishes observed included macrourids (cf. Coryphaenoides, some with visible gnathiid ectoparasites), Ophidiidae cusk eels, lizardfish (Bathysaurus sp.), Halosaurs (Aldrovandia sp.), and tripod fish (Bathypterois sp.).

Wood falls represented an alternative habitat from the rocks, housing associated gastropods, serpulid polychaetes, and limpets.

The Septentrional Fault, which extends from east of Hispaniola to Mona Seamount/Block, is a major strike slip fault (a type of fault where two pieces of theEarth’s crust slide past each other) that could potentially be the source of a large earthquake. A curious feature of the Septentrional Fault is that it appears to end in an approximately 1,000-meter deep hole just west of Mona Canyon (unusual because faults do not typically terminate in this way).

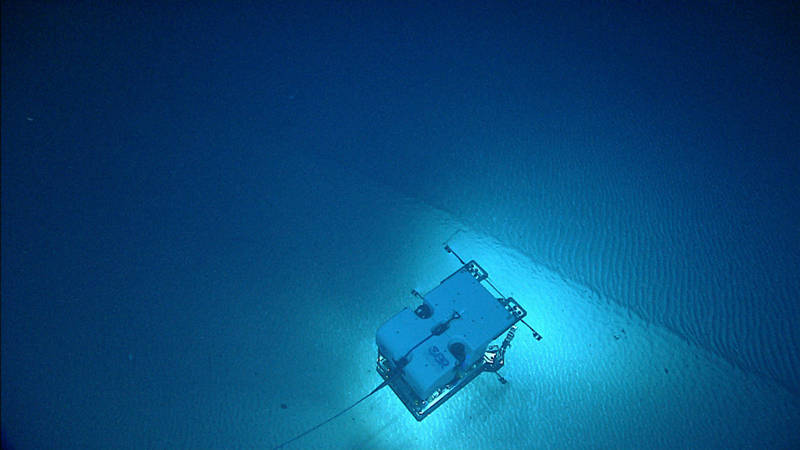

ROV Deep Discoverer imaging a series of rippled bedforms. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

Dive 2 of the expedition went into this hole with the goal of looking for evidence of movement along the fault (deformation of the rocks/sediment) and clues to the origin of the hole. While we didn’t find any deformation features related to the fault during this dive, we came across sediment waves and ripple fields that stand as a testament to the strength of ocean currents even at water depths over 3,000 meters. We also saw rock types we believe are related to the region’s early volcanic construction.

Concentrated within the ripples was a combination of detritus (Sargassum and sea grass) and pteropod tests. Periodically, trash was found on the seafloor, including plastic cups and sheet metal.

There was a distinct lack of holothurians, possibly because the high flow environment inhibits the deposition of organic material, thus limiting the food available to these deposit feeders. Fishes observed included rattails (Coryphaenoides spp.) and Bathysaurus mollis. The large boulders were practically devoid of attached, sessile megafauna, where the few animals observed included hormathiidae anemones, slime sea star (Hymenaster, 3,637 meters), brisingid seastars, and crinoids. Bamboo plant detritus represented a diverse habitat, populated by brisingid sea stars, limpets, and possibly bivalves.

White Munidopsis squat lobsters were found mid-way through the dive crawling on boulders. Other crustaceans included a hermit crab with an anemone house; similar hermits have been observed in other deep-sea regions. Carnivorous sponges (Cladorhizidae) were observed as well as other species of demospongiae and hexactinellidae. One bamboo coral colony was encountered, with its large polyps oriented upward into the water column above.

Overall, the diversity and density of megafauna within this area were low.

Large carbonate block encountered during Dive 6. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

Mona Passage is an almost entirely submerged section of the island arc and carbonate platform, with water depths generally between 100-700 meters, but as deep at 1,000 meters. The morphology of the seafloor in this region is composed of a mix of erosional, karst, depositional, and fault features, overprinted on the original layered fabric of the carbonate platform which is exposed almost everywhere across the passage.

The flat-topped islands located centrally within the passage, Isla de Mona and the smaller Isla Monito, are emergent outcroppings of the carbonate platform, while Isla Desecheo is composed of island arc volcanics, similar to those rocks seen on dive 2 and 5.

Dives at ‘Pichincho’ (Dive 3) and the ‘Platform’ (Dive 6) traversed seafloor showing evidence of extensive erosion by the strong bottom currents that pass through the passage and karst morphologies (features of the rocks that result from dissolution by surface or ground water that occurs when the rocks are exposed above sea level). The pits and depressions created by erosion were filled with calcareous material, including dead corals and shells. In addition, we saw some large blocks of the carbonate rock that had become detached from the exposed cliffs, illustrating that the seafloor in this tectonically active region is quite unstable.

Large boulders contained various types of attached sponges, asteroids, ophiuroids, and a very large nemertean was observed crawling along the rock surface. Other habitats included sponges that housed barnacles and zoanthids, Holopus (barnacle crinoids), and shrimp.

Evidence of past erosion that ROV Deep Discoverer encountered during Dive 3. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Cusk eels were documented interacting with sponge habitats, and other fish were associated with the rock outcrops and sediment drape, including beardfish (Polymixia nobilis), greeneyes (Chlorophthalmus agassizi), deepwater cardinalfish (Epigonus spp.), scorpionfishes, slope bass (Synphysanodon cf. berryi), and sharktooth moray eel (Gymnothorax maderensis). Incredible imagery of a Chaunax pictus “walking” along the seafloor was captured and an unknown, new species of labridae, was also observed.

Corals included solitary cup corals (Javania sp. and at least one other species), small primnoid and plexaurid octocorals, stylasterid hydrocorals, black corals (whip type with ophiuroid associates), an unknown chrysogorgiidae with a chirostylid squat lobster, and gold coral. At around 300 meters, different types of corals were observed, including colonial scleractinians attached to the wall and oriented downward, and the tops of the ledges were populated by various sponges and sea fans (octocorals), squat lobsters, and hermit crabs.

As ROV Deep Discoverer approached, this sea toad (Chaunax sp.) “walked” away. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Several species of asteroids were observed, including one feeding on a sponge. Notably, several sponges had large holes in the tissue, possible a consequence of the asteroid predation.

While there was abundant substrate for corals, very few were observed, both in terms of abundance and diversity, which may be a consequence of high water temperatures and/or food supply. Fresh failure areas of the rock were relatively devoid of fauna, whereas older, heavily eroded crusts were populated by mostly sponges.

During our dive on Pichincho, we encountered a diversity of sponges and a few barnacle crinoids, seen here in the middle of the picture. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 702 KB).

This sharktooth moray eel was spotted during Dive 03 in the Mona Passage. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

The dive on the east side of the Mona Passage was conducted at a similar depth range as Pichincho (Dive 3), and contrasted in several important ways in terms of the ecology and biodiversity of fishes and invertebrates.

Overall, there was a higher diversity of corals, sponges, and fishes observed during this dive compared with other dives in Mona Passage. At least 35 putative species of fishes were documented, including spike fish (new for the expedition), greeneyes (Chlorophthalmus agassizi), scorpion fishes, beard fish (Polymixia, spp.), two to three shark species (e.g., Scyliorhinus spp.), Gephyroberyx darwinii (Darwin’s slimehead), cusk eels, and sea robins (Peristedion spp.). A slender dory (Parazen pacificus) was imaged puffing up the sediment, possibly trying to feed. Other examples of predatory interactions included an urchin eating coral tissue. Toward the end of the dive, the queen snapper (Etelis oculatus), the target fish species for the dive, was observed.

Throughout the dive, several coral species were observed, including black corals (branched and unbranched forms), soft corals, colonial and solitary scleractinians, primnoid and chrysogorgiid octocorals, and hydrocorals (stylasterids). However, along the top of the platform, many of the coral colonies were small (less than 10-centimeter tall colonies). Coral associates observed included crustaceans (crabs, chirostylid squat lobsters) and large basket stars (Gorgonocephalidae).

A shrimp associate with a very serrated rostrum inhabiting a glass sponge. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.9 MB).

A brittle star associate with a lace coral demonstrates symbiosis in the deep sea. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

On the sediment surface, a new species of squat lobster for the expedition, genus Agononida sp., was observed. Several yellow terebellid polychaetes were present on the sediment surface, with their tentacles undulating in the water column. Other notable observations included a few large slit shell gastropods on the soft sediment substrate, a large nemertean crawling along the rock surface and interesting tunicates, including predatory forms and flower shaped forms found attached to the rocks. Other cnidarians documented on the dive included colonial zoanthiids attached to coiled stalks and fans, and a few anemones not observed on previous dives.

Near the top of the scarp there were several pits/depressions that contained mostly dead coral rubble. An ophiuroid was seen crawling onto the rostrum of an armored sea robin (Peristedion sp.). Additionally, several sponge species were found encrusting the rock substrate, including Corallistidae and Astrophorids. Several types of echinoderms were encountered, including sea stars (e.g., brisingids, Tamaria passiflora); crinoids (e.g., Holopus sp.); urchins (e.g., Cidaris spp.); and holothurians (at least two species), some of which had amphipod associates.

Brittle stars may perch on corals to feed on food particles in the water column. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 948 KB).

Steep temperature and dissolved oxygen gradients were noted during the dive, including a large decrease in dissolved oxygen near the approach to the top of the ridge.

A rarely observed spike fish imaged during our dive at Platform. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploring Puerto Rico’s Seamounts, Trenches, and Troughs. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

While there were only a few dives conducted within this region, this exploration and one carried out in 2013 by the E/V Nautilus are producing major insights into the interactions between seafloor morphology, substrate type, and the associated benthic communities. In addition, several hypotheses have been developed regarding the connectivity, diversity, and overall ecology of this region as a result of these direct observations.

Data collected during the dives will help the ongoing analysis of geologic hazards (earthquakes, landslides, and tsunamis) originating in the waters of the Northeast Caribbean as well as aiding the fisheries management community in developing a more complete understanding of fish habitats in the region.