By Steve Gittings, NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

April 18, 2014

A king crab, a white anemone, and stoloniferous corals perch on ship hardware above the surrounding mud. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

On April 17, we spent a wonderful day ashore at the Texas A&M Galveston Exploration Command Center, watching hi-def video sent by remotely operated vehicle (ROV) operators who did amazing work while bouncing around in less-than-perfect conditions on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer over Monterrey Shipwrecks A and C.

Thanks to telepresence technology, anyone with Internet could follow the exploration. Here, Oliver and Edwin Tartt watch the mission over breakfast while their family is on vacation in South Carolina. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB). Video highlights from Dive 05.

We scanned the contents of much of Wreck C to see what’s growing on the priceless and fascinating artifacts while archaeologists interpreted the scene, trying to identify everything they could. As biologists, our objective was to compare the growth on three wrecks that we’ll be visiting this week and to compare it to life on natural habitats in the Gulf of Mexico.

It was evident from the start that animals prefer certain types of surfaces over others. Mats of flowery soft corals and small, branching hydroids covered old pieces of iron hardware from the ship, as well as the ballast stones used to stabilize the ship and keep it upright while under sail. Large orange flytrap and white anemones have found their way to anchors and other hard structures sticking up off the bottom. Earthenware or other materials with rough surfaces hosted similar species along with solitary hard corals and polychaete tubeworms.

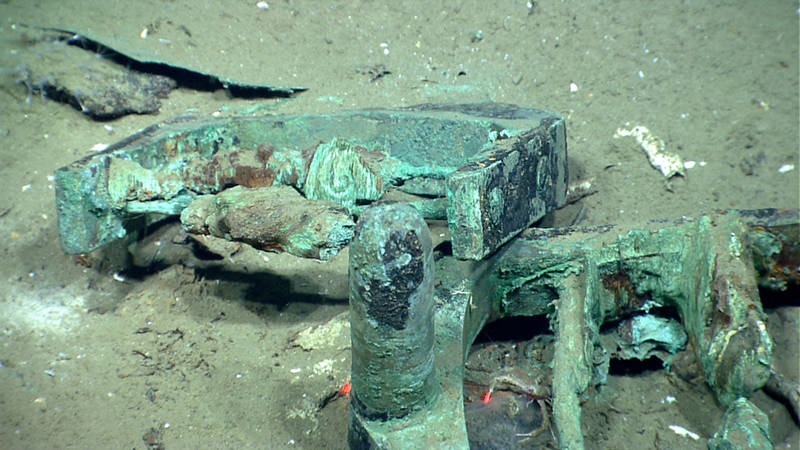

Copper and brass has stayed free of marine growth for nearly 200 years! Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

Glass bottles and smooth ceramic containers were much less populated, perhaps due to their smooth texture, or in the case of the ceramics, perhaps because of lead in the glaze used on their outer surfaces. Anything containing copper, including the sheathing on the hull or brass instruments and fittings, had almost no growth, showing why copper was used to protect hulls from wood-boring shipworms and from barnacles and other growth that would slow a ship down.

In the sand, the remains of shipworms told the story of masts, decks, bulkheads, and a hull eaten to oblivion. Without a food source, the animals, which are actually bivalves, simply died, leaving only the calcified remains of their shells. Taking their place, tucked away in the many crevices created by the wreck, were squat lobsters and other small invertebrates. Around the wreck site scampered a few king crabs, golden crabs, and deep-sea red crabs. Several fish hid beneath artifacts, likely confused by the bright lights in the otherwise pitch black darkness at 4,000 feet.

The tubes of shipworms litter areas once covered with wood. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Exploration of the Gulf of Mexico 2014. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

As a biologist, the dive was an insight into the role of ships even after they sever their ties with the human race. Ships give life to civilizations. When they sink, lives are lost in horrible ways, as we were so tragically reminded in South Korea just the day before our dive. On the seabed, ships serve a new role in giving rise to other forms of life while they themselves slowly revert to the basic elements of their construction. As with so many things, Nature seems to have her way with the marvels of human ingenuity.