by Andrea M. Quattrini, Temple University

July 14, 2013

A Rhinochimera (Harriotta sp.) swims 10 meters above the seafloor. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 974 KB).

Over the past two days, the remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer (ROV D2) explored steep slopes along the west and east walls of Hydrographer Canyon. These represented the first two of many dives in a deepwater submarine canyon for the Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition.

During each dive the science team planned to survey ~ 1,000 meters of the seafloor, but the ROV D2 only managed to survey a portion of the dive tracks. This was not due to technological or operational issues. These abbreviated surveys were due to the scientist’s excitement at discovering what appeared to be recently colonized deep-sea coral habitat and an amazingly high diversity of organisms in this canyon ecosystem. Obviously such exciting discoveries required a great deal of time to document.

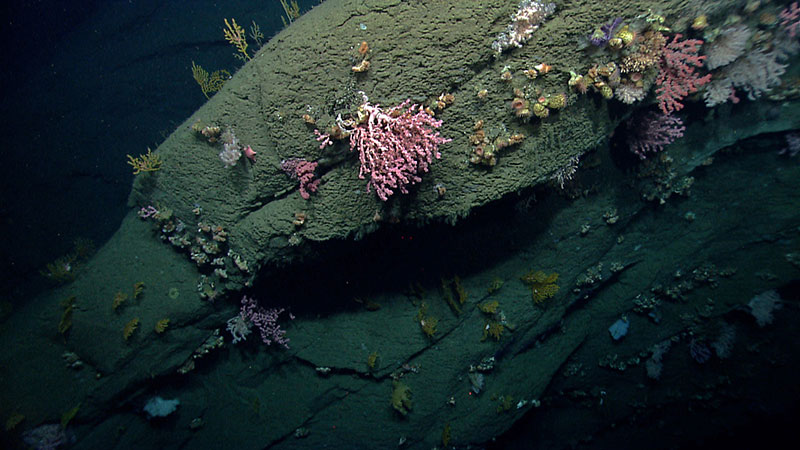

Hydrographer Canyon proved to be a diverse habitat for deep-sea corals. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

As D2 descended to the bottom of the seafloor almost a mile under the surface, scientists began to see for the first time the diversity, type, and number of foundation species (e.g., corals and sponges) in this region of Hydrographer Canyon. Habitat-forming species increase habitat heterogeneity, thereby attracting a diversity of other fauna, including shrimps, squat lobsters, amphipods, and isopods.

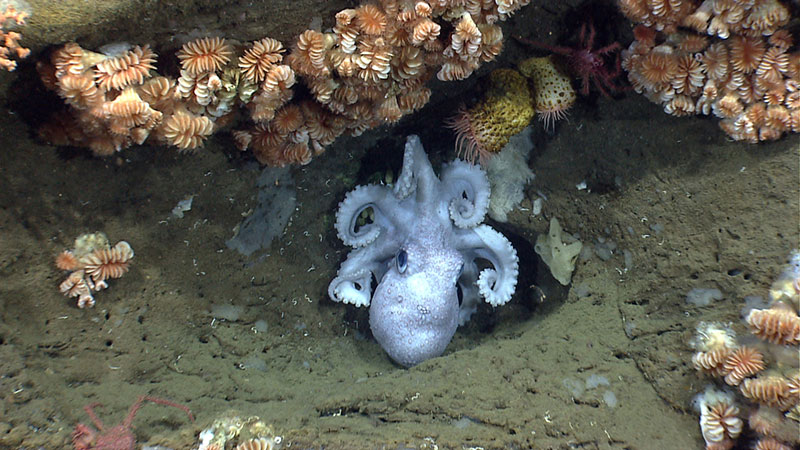

In addition, some species provide a foundation on which other species can inhabit or even lay their eggs. For example, certain species of squat lobsters and brittle stars can be seen living directly on octocorals and black corals, and the same species are rarely (if ever) observed on the surrounding substrate. We observed these common associations throughout Hydrographer canyon, including two noteworthy observations at ~800 meters depth: a catshark eggcase attached to a bamboo coral and cephalopod eggs inside a glass sponge.

An octopus guards her eggs under an overhang in Hydrographer Canyon. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

During the two dives in Hydrographer Canyon, numerous species of sponges (Phylum Porifera) and at least 15 species of corals (Phylum Cnidaria) were observed on the tops, faces, and overhangs of vertical canyon walls. Coral species included stony corals, black corals, and octocorals, some of which have been observed in other regions including the canyons in the U.S. mid-Atlantic region and in the Bay of Biscay.

Interestingly, some of these species were more common along certain habitat features. One of the most abundant corals, the bubblegum coral Paragorgia arborea, was most common along the edges of the canyon walls; both red and white color morphotypes were observed. In contrast, Paramuricea spp. often occurred on the tops of walls and the hard coral Desmophyllum diacanthus were attached to the underside of ledges. Further community differences were evident in the shallower and deeper regions of Hydrographer Canyon.

A coral recruit and a glass sponge along the wall of Hydrographer Canyon. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 791 KB).

Any indication that deep-sea corals have recruited to the seafloor (i.e., really small individuals) is extremely rare. As soon as we reached the seafloor, we noted numerous individuals of many species, including bubblegum coral, Paramuricea sp., and Anthomastus sp., which were less than a few centimeters in length. These habitats included small rocks in the sediment, rock, ledges, and steep canyon walls. A rare observation suggesting that the habitats and conditions in this area were recently made suitable for colonization.

ROV D2 explores steep slopes and cliff faces along the walls of Hydrographer Canyon. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 871 KB).

As scientists continue to explore new areas of the seafloor, new species, new communities, and new relationships between fauna will most certainly be found. Although exploration is key to our mission, the discovery of recruitment and new habitats in unknown areas of the seafloor has additional significant implications. With the use of exploration, we will continue to refine species distributions that will allow us to predict where these fauna may be present in other, perhaps vulnerable, habitats. These insights will allow the management community to effectively design management scenarios to protect and conserve biodiversity and living resources in the deep sea.