by Peter Etnoyer, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science

August 5, 2013

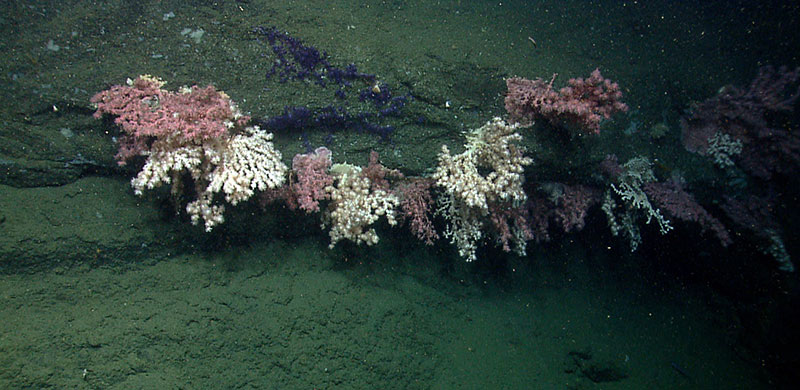

Abundance and diversity of corals are just some of ecosystem characteristics that can be gleaned from the live Okeanos Explorer feeds. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Working with a telepresence-enabled ship like NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer is a bit like 'drinking from the firehose' when it comes to digital information. The ship and crew battle wind and waves, but here on ‘the beach’ we battle with overloaded networks and overheated computers. We deal with big data in real time. The steady stream of high-resolution images, water chemistry, and navigation from the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) require high bandwidth (4 mb/sec) and push the limits of our technology.

NOAA works to capture this information partly because it helps to accomplish the goals laid out in the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Reauthorization Act of 2006 (MRSA). MRSA provides NOAA with science and management authorities related to deep-sea corals. It also authorizes regional fishery management councils to designate zones that protect deep-sea corals from damage by fishing gear. Observations made during the 2013 Northeast US Canyon Expedition will help U.S. East Coast fishery managers to determine whether and where protection zones for deep-sea corals and in the canyons are necessary.

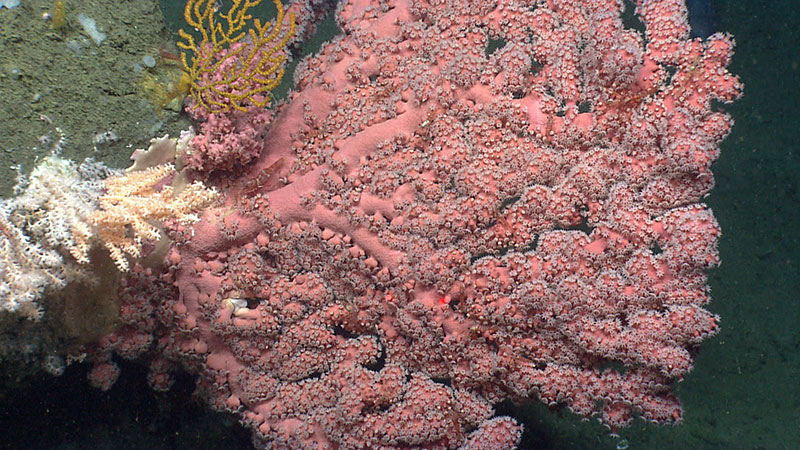

A colony with bright color and full branches with many extended polyps would be considered healthy or in good condition. The red lasers (red dots in the photo) are 10 centimeters apart and are used for scale and age estimates. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

NOAA’s Deep-Sea Coral Research and Technology Program works with partners to report the location of deep-sea corals observed during missions like this to fishery management councils. If you’ve been following along, it's probably clear that the location of corals is just one small piece of information that can be gleaned from the live image stream. Thanks to participating scientists in chat rooms and on-call, we can identify organisms like ‘Paragorgia’ or bubblegum corals, and ‘Paramuricea’ or sea fans. We can also count corals to quantify how many and what types we see. This is how we measure abundance and diversity.

Another piece of information available from the live image stream is the size of coral colonies. Colonies are scaled by the red lasers on the ROV set to 10 centimeters distance. Image processing software lets researchers use this scale to extrapolate other measures like colony height, width, area, and thickness. These measures are important because large corals are hundreds of years old and vulnerable to disturbance. Things grow slowly in the deep sea, so disturbed colonies and communities may take a long time to recover or reproduce.

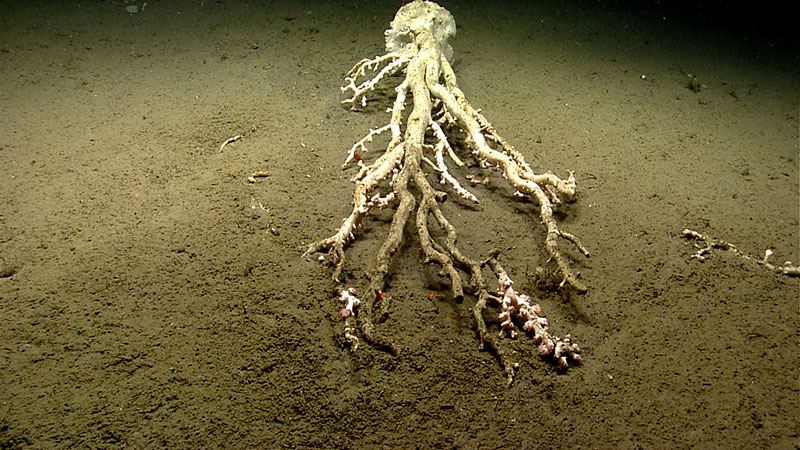

A large toppled Paragorgia or bubblegum coral colony was observed in Hydrographer Canyon. The red lasers (red dots in the photo) are 10 centimeters apart and are used for scale and age estimates. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

Health and condition of corals is another quality that can be measured in images. A colony with bright color and full branches with many extended polyps would be considered good condition. A toppled or discolored colony with bare branches would be considered injured. Toppling can occur naturally, due to landslides, or by human impacts from fishing gear like trawls, crab pots, and longlines. Scientists and managers strive to be careful about assigning cause of injury by looking for clear evidence of these different types of interactions.

It truly takes a village to acquire and interpret all this information and then make it publicly available. Ship’s crew, ROV pilots, scientists, IT experts, and managers are all necessary to make it happen. At the heart of it, telepresence is people powered, yet it is also a major technological advance helping all of us to work together towards shared goals of exploration and management – a known and healthy ocean.

Longlines, such as the one seen here, can cause injury to coral. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).