by Jamie Austin, University of Texas at Austin, John A. and Katherine G. Jackson School of Geosciences, Institute for Geophysics

August 11, 2013

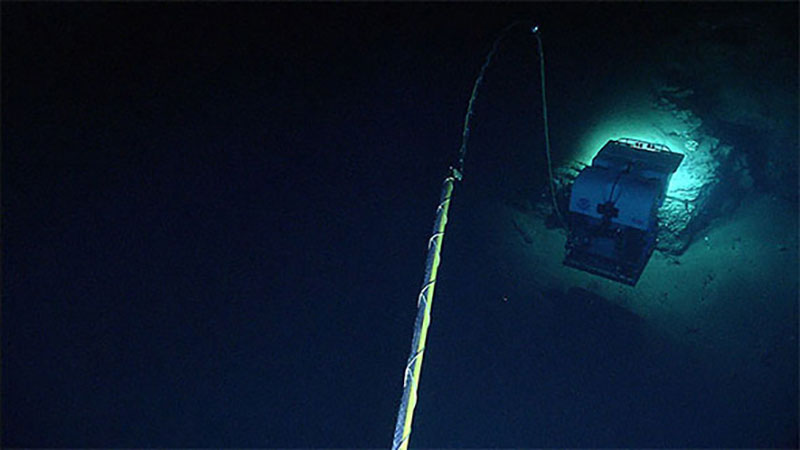

A view of the Deep Discoverer remotely operated vehicle (ROV) from the Seirios camera sled in Heezen Canyon, shows just how “up close and personal” the ROV can get to rock outcrops and associated biology. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download image (jpg, 38.6 KB).

Submarine canyons, undersea "sinuous valleys" indenting the continental slope off the central and northeastern United States, are one of the East Coast continental margin's most prominent features. Some of these canyons are tens of millions of years old, kept open by periodic erosional forces generated by many processes. The processes that keep the canyons open include:

A scalloped portion of the wall in Heezen Canyon. The near-horizontal cracks are breaks between bedding (depositional layers), while the near-vertical cracks are fractures or joints that form when the buried rocks depressurize as they reach the seafloor through erosion. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download image (jpg, 113 KB).

An example of how, in Heezen Canyon, biology (in this case a hake) uses fractures in the rocks as suitable habitat. Fractures can provide critters with opportunities to hide from predators or to get away from erosive downslope currents that continually shape canyon walls. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download image (jpg, 129 KB).

The primary goal of the Okeanos Explorer expedition that we are currently engaged in is to understand biological colonization and its relationships to the complex topography of these canyons. Many of these canyons have never been studied in detail, and those that have been visited have not been looked at in detail by remotely operated vehicles (ROV), supported by the kinds of detailed seafloor maps which the NOAA Okeanos ship can create before we dive.

I am presently joining the expedition from the Inner Space Center at the University of Rhode Island. I served as the science lead aboard the ship for an expedition to the Gulf of Mexico in April of 2012. I guarantee that sitting here right now, with headphones on, communicating in real time with the shipboard science party, and looking at the huge screens in the Inner Space Center that are broadcasting the ROV imagery in real time, is every bit as exciting as being on the ship.

A boulder encrusted with biology – anemones and corals. Note the variety of rock sizes in the depression or moat around the boulder; these rocks may be dropstones, which reached the seafloor thousands of years ago as icebergs (products of the last continental ice sheet) floating at the surface melted and released them. The depression around the boulder is caused by currents sweeping along the seafloor and provides habitat for a variety of organisms such as fish, crabs, and shrimp. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition 2013. Download image (jpg, 76.0 KB).