by Amanda Demopoulos, Benthic Research Ecologist, U.S. Geological Survey

A species of rockling (Family Lotidae) nestles within beds of chemosynthetic mussels (Bathymodiolus). Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download image (jpg, 114 KB).

Submarine canyons are found throughout the world, representing complex seafloor features that link the upper continental shelf to the abyssal plain. They punctuate the margin by incising the shelf, creating scenic seascapes reminiscent of their terrestrial counterparts.

Canyons encompass dynamic areas, containing steep slopes that can be highly unstable, with variable current regimes, and serve as deposit centers for sediment and organic matter. There are at least 660 known submarine canyons worldwide, although few have been mapped extensively using modern methods, let alone explored and investigated via remotely operated vehicles (ROV).

Numerous major and minor canyons exist along the continental margin off the U.S. East Coast, but few have been visually explored to any major extent. Scientific investigations of these canyons require an interdisciplinary approach, including geologists, physical oceanographers, biologists, ecologists and modelers to fully comprehend the canyon environment.

A bythitid meanders through a cluster of corals, including red Paragorgia, white Lophelia pertusa, and basket stars. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download image (jpg, 90 KB).

Submarine canyons are geologically and morphologically diverse environments. They are formed from various erosional processes, including rivers, biological activities (e.g., reworking of sediments by fish and invertebrates), tidal currents, and internal waves, all of which may influence canyon development and morphology. The U.S. northeast continental margin contains approximately 40 shelf-breaching canyons, so named due to their relationship to the shelf edge.

During the Pleistocene epoch (~ 2.6 million – 11,700 years ago) when there were periods of low sea level stands, rivers created incisions in the shelf, supplying large volumes of sediment that was transported through canyons, forming deep-sea fans along the adjacent slope and abyssal plain. Canyon slope environments are centers of active sediment deposition, primarily composed of fine sediments derived from the upper shelf or from the resupsension of material off the seafloor. Hard substrates, such as canyon walls, ridges, rocks, and boulders, are rugged features that are indicative of the complex flow and sediment transport environment found within canyons.

Within the U.S. northeast Atlantic margin, Hudson Canyon represents one of the most well-studied examples of a shelf-breaching canyon. It has very steep slopes, a deeply incised valley, and its channel extends over 200 miles from the shelf to the deep continental rise, representing a dynamic feature on the seafloor.

Google Earth image of Hudson Canyon. Image courtesy of Google Earth. Download image (jpg, 54 KB).

Often considered biological hotspots, submarine canyon ecosystems are influenced by the hydrodynamic regime (turbidity currents, tidal flows, and internal waves) and topographic complexity (steep walls, rock outcrops, and sediment waves). Diverse habitats, including cliff walls, rocks, boulders, deep-sea corals, chemosynthetic ecosystems, and soft sediments, host various invertebrate and fish species.

The flow environment, food supply, and tectonic nature all interact to allow for discrete communities of organisms to thrive in the heterogeneous environments found within canyons. For example, steep canyon walls allow for swift moving currents to transfer and resuspend sediment, providing food for suspension feeders, including deep-sea corals.

Submarine canyons off the U.S. East Coast are home to deep-sea scleractinians, or stony corals, including reef-building Lophelia pertusa, as well as Solenosmilia variabilis, and cup corals, such as Desmophyllum. Various octocorals, including Primnoa resedaeformis, Paragorgia arborea and Paramuricea grandis, and Antipatharians or black corals, such as Bathypathes sp., also have been observed within the region, attached to canyon hard substrates.

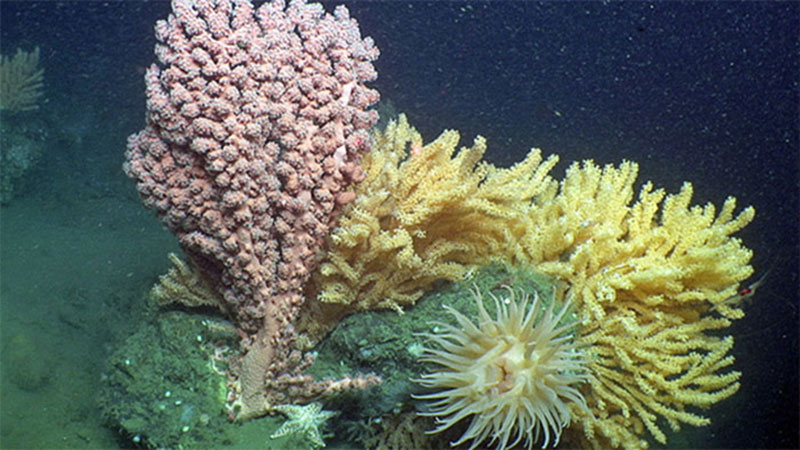

Other animals associated with U.S. Atlantic canyons include several species of fish, anemones, sponges, and sea stars. Soft sediments found within the canyon axis and mouth of the canyon are often dominated by surface deposit feeders, including holothurians, or sea cucumbers, that provide important ecosystem functions by consuming large volumes of organic-rich sediments and consequently cycling organic matter on the seafloor.

Often multiple species of invertebrates are found co-occurring on rock ledges and canyon walls. Here a brisingid sea star, an octopus, bivalves, and several individuals of the cup coral, Desmophyllum, are found in close proximity to one another. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download image (jpg, 114 KB).

Understanding the interactions among the flow environment, sediment supply, habitat complexity, and faunal associations remain rich areas of research; thus every dive within the canyons will likely yield new information on the geology and ecology of these complex and relatively unknown seafloor environments.

Recent geological and biological research conducted by scientists from NOAA, BOEM, USGS, and academic institutions has helped guide this community-driven mission on the Okeanos Explorer. Given the variety of canyons found along the U.S. Atlantic margin, and the diversity of habitats and geology within, exploration of these environments will yield critical information regarding the habitat associations of deep-sea corals, sponges, fish, and other organisms, and this information will be used to help develop conservation and management plans for these communities.

Bubblegum coral (Paragorgia), several colonies of Primnoa, an anemone, and sea star all inhabiting a boulder within the canyon. Image courtesy of Deepwater Canyons 2013 - Pathways to the Abyss, NOAA-OER/BOEM/USGS. Download image (jpg, 107 KB).