By Mike Vecchione, NOAA/NMFS National Systematics Laboratory - National Museum of Natural History

April 21, 2012

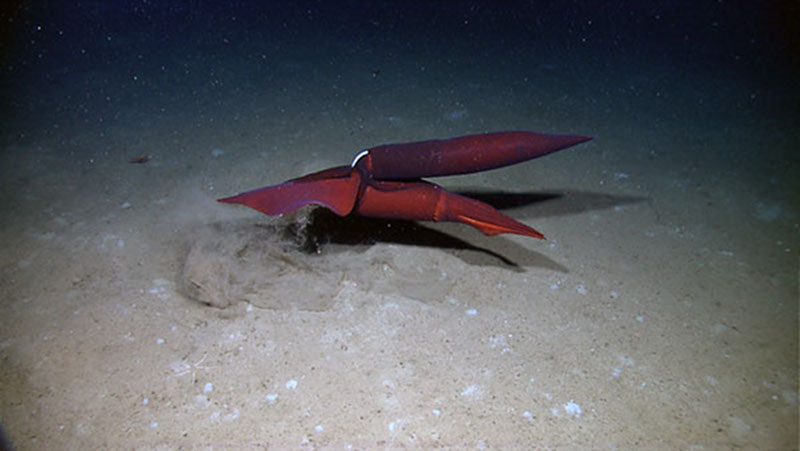

Many deep-sea animals are red. The only light found in the depths of the ocean is blue. Blue light does not reflect off of red animals, and makes them much more difficult to see unless you have a remotely operated vehicle with bright white lights. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.0 MB).

A famous quote attributed to Louis Pasteur translates as, “In the field of observation chance only favors the prepared mind.”

As I mentioned in a mission log prepared during Leg 2 of this Okeanos Explorer cruise, a population of sperm whales permanently resides in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Presumably, this part of the Gulf is a good place for the whales to find food, so I have been looking for the big squids that these whales dive deep to catch.

Video footage captured by the Little Hercules ROV and camera platform during the April 21 ROV dive from NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer during the Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. The dive was conducted in Green Canyon lease block 470 and operations were concentrated around the top of a topographic high – perhaps the crest of a surfacing salt dome. A predominantly extinct brine pool and many small drainage channels were observed during the dive, presumably the remnants of old brine flow features. Small amounts of brine were also observed, including drainage channels filled with brine feeding a small pool. Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download (mp4, 208.7 MB).

Unexpectedly, on the first dive of Leg 3, we found some mysterious furrows in the bottom sediment. In the Mediterranean, similar furrows have been interpreted as feeding marks of deep-diving toothed whales. Although we don’t know that to be the case here, it seems possible to me.

Impressions, called furrows, were found on the seafloor. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Why would a squid-eating whale take a bite out of the bottom? A possible answer came later in that same dive. Little Hercules happened upon a large squid that was just inches above the bottom of the seafloor. If a whale wanted to eat this squid, the whale would probably hit the bottom, possibly leaving a furrow with its narrow bottom jaw, similar to what we had seen.

This squid sighting was not an isolated observation. Nearby on the next dive, the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) came across an even more interesting site for someone like me, who studies deep-sea cephalopods (squids, octopods, and their relatives). When first seen dimly in the distance, it was difficult to interpret what we were seeing. As the ROV approached, the apparition resolved into a pair of large squid, similar to the one from the previous day. One squid was holding onto the other.

Two squids attempt to mate in the Gulf of Mexico. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

What you see is the male squid upside down on top of the female, holding her just behind the fin. The white structure is the end of the male reproductive tract, which he is using to implant sperm packages on the female. Even for a squid biologist, this is still a little confusing because where he is placing his spermatophores is nowhere near where her eggs come out. Answering why this is so will be a subject for future research. So what are these squid? Unfortunately, I can’t be absolutely certain because not all of the characteristics necessary for identification are visible. However, by eliminating all other large squid species known from this area, I am pretty sure that they are a species of scaled squid, Pholidoteuthis adami (see http://tolweb.org/Pholidoteuthis_adami/19853). Every time I have seen this species from a submersible, it has been very close to the bottom at depths between 200 and 1,000 meters. Very little is known about the behavior of deep-sea cephalopods, so every chance observation like this is important. In addition to these observations, on this cruise we collected detailed observations on a pelagic (constantly swimming) octopod called Japetella diaphana and a bottom-living octopod Callistoctopus sp., as well as brief glimpses of squids from the genus Mastigoteuthis and the families Ommastrephidae and Enoploteuthidae.

Video footage of two squids mating captured by the Little Hercules ROV and camera platform during the April 21 ROV dive from NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer during the Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Video courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Gulf of Mexico Expedition 2012. Download (mp4, 118.2 MB).

Because I have trawled quite a lot in the northern Gulf of Mexico, I know there are over 50 species here. Finding six species might not seem like that many, but in other areas where I have both fished to collect specimens and used submersibles for direct observation, a ratio of about 10:1 is normal because the nets have a better ability to sweep.

What the nets cannot do, but submersibles can, is tell us exactly where the animals were and give us a glimpse into what they are doing, like the mating squids we saw close to the bottom. The different tools give us different parts of the picture. That is why it is important to use as many tools as possible to explore the mysteries of the deep sea.