By Tom Weber and

Larry Mayer - University of New Hampshire, Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping

What Little Herc was looking at: a plume of methane bubbles rising from the seabed. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download image (jpg, 45 KB).

The northern Gulf of Mexico is well known to contain a large number of naturally occurring gas seeps, the presence of which have been inferred from seismic data, satellite remote sensing of oil slicks, and single beam echo sounder data. On a recent cruise with the Okeanos Explorer, we evaluated how well the deepwater multibeam echosounder (MBES) would work for mapping gas seeps in the deep ocean.

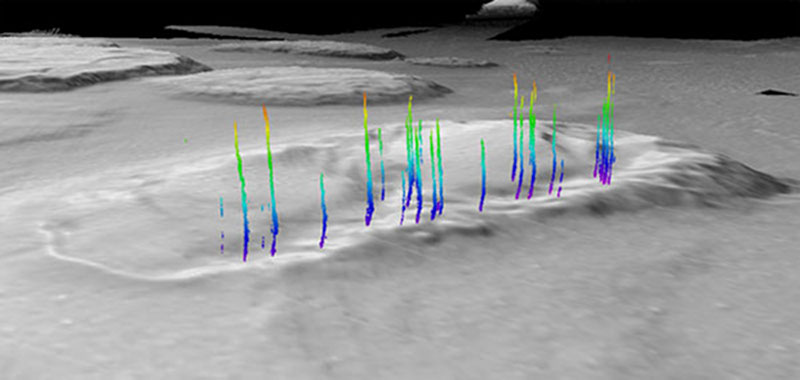

Acoustic observations of seeps (color coded by depth) rising from the western edge of the Biloxi Dome in the northern Gulf of Mexico. These data are extracted from the 30 kHz MBES on the Okeanos Explorer. Processed data courtesy of Tom Weber, UNH-CCOM. Download image (jpg, 41 KB).

It turned out that the system worked extremely well for finding gas rising through the water column in this environment – during our 2011 cruise we made hundreds of observations of natural gas seeps, pinpointing their source on the seafloor to within about 25 meters.

As excited as we were to be able to map seeps and examine their morphology (how high we see them rise in the water column, their relative acoustic strength, whether they are ‘bent over’ in the current) with the 30 kHz MBES on the Okeanos Explorer in 2011, we have more questions now than ever before.

Many of our questions seem simple – but become very difficult to answer when working a mile below the ocean surface. For example, we wonder if the seeps we observe look like a narrow plume bubbling out from one isolated spot on the seafloor, or are the bubbles slowly percolating out from a wider region (the footprint of our multibeam in these depths of the waters is a few tens of meters across). We also wonder what size bubbles we are actually seeing, at what rate they are exiting the seafloor, and whether we can use our acoustic observations of the plume morphology to help determine when oil may be leaking from the seafloor in addition to gas (note that the acoustic systems we are using are very sensitive to gas bubbles, but not very sensitive to oil when no gas is present). We have also observed bubble plumes rising through the water column where we did not expect them to be and simply want to know more about why these bubbles are showing up where they are. Eventually we would hope to use the types of measurements we are making to get a better handle on the overall flux of gas from seeps into the Gulf of Mexico.

During Leg II of this cruise, the expedition team was able to locate an active seep that was located only a few meters from a seep we had previously imaged in 2011, giving us an early indication of the types of things we might find during Leg III. Using both the estimate seep position from 2011 and the scanning sonars on the remotely operated vehicle (ROV), Little Hercules’s pilots successfully navigated to a seep bubbling up through a mussel bed from an isolated spot on the seafloor, and were even able to identify a hydrate formation on the underside of one of the mussels. Later on in the dive, they found a second seep site that looked very different than the first: bubbles at the second site were slowly rising from a much wider (several meters) region of the seabed. As we continue this type of exploration during Leg III we’ll be looking at several more seeps like these, working hard to understand what we are seeing in the MBES data and how best to exploit the unique observational abilities of the Okeanos Explorer.

Little Herc investigating a seep rising from a mussel bed on the southern edge of the Pascagoula Dome in the northern Gulf of Mexico during Leg II of the expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download image (jpg, 18 KB).

A hydrate ‘beard’ on the underside of a mussel at the methane bubble seep site. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download image (jpg, 66 KB).