By Jack B. Irion, Regional Preservation Officer - Bureau of Ocean Energy Management

Photograph of the remains of the ships’ steering gear from the wreck of a wooden hulled sailing ship in over 7,000 feet of water. Image courtesy of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. Download image (jpg, 146 KB).

NOAA’s Okeanos Explorer is cruising in the wake of 500 years of ships of discovery in the Gulf of Mexico. Beginning with Spanish conquistadors searching for gold and glory and continuing with oil and gas survey ships hunting for petroleum reserves miles below the surface, the rich resources of the Gulf has been a prize fought over from the throne rooms of Europe to the boardrooms of Houston and London. Unlike those early mariners sailing under the flags of Spain or France, the Okeanos Explorer is purely on a mission of science and knowledge; one that seeks to better understand the diversity of the undersea environment and improve our ability to serve as its stewards and protectors.

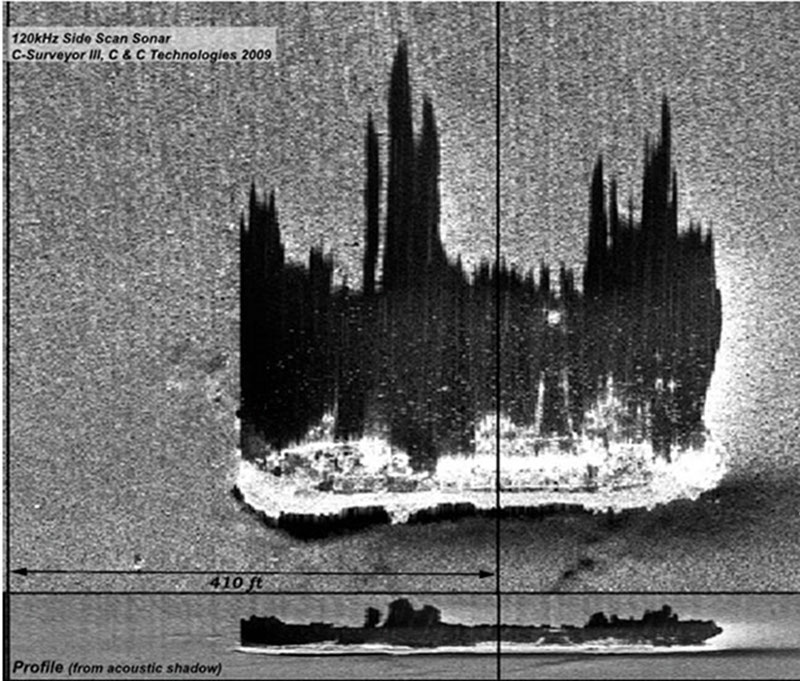

Sidescan sonar image of the wreck of Gulf Oil, an oil tanker sunk by a German U-boat during World War II. Image courtesy of C&C Technologies. Download image (jpg, 56 KB).

Gulf Shipwrecks

One means of protecting the future is by understanding the past. Clues to understanding the rich maritime heritage of the Gulf lie entombed in thousands of shipwrecks resting on the ocean floor throughout the Gulf. Shipwrecks are like time capsules preserving a single moment in time. From them, we can learn what life was like for people making their living from the sea hundreds of years ago. We estimate that over 4,000 shipwrecks rest on the floor of the Gulf of Mexico from its nearshore shallows to its deepest abyss. During this cruise, Okeanos Explorer’s cameras will explore, for the first time, a handful of these shipwrecks thousands of feet beneath the water’s surface.

One of the fortunate by-products of intense exploration for oil and gas resources in the Gulf is that many areas of the seafloor are imaged using remote sensing instruments like sidescan sonar. Sonar paints a picture of the seafloor using reflected sound waves. The shipwrecks that Okeanos Explorer will be exploring were first discovered as sonar targets and reported to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the federal agency charged with overseeing the oil industry and with protecting the Gulf’s natural and cultural resources.

Over 600 shipwrecks and possible shipwrecks have been discovered in the northern Gulf of Mexico, mostly through oil industry sonar surveys in water depths up to 9,800 feet (2,316 meters), and 28 of these ships have been confirmed visually as historic vessels, either by divers or by remotely operated vehicles such as Okeanos Explorer’s Little Hercules. We hope to add to that list during this cruise.

Cannon recovered by archaeologists from an early 19th century shipwreck in 4,000 feet of water the Gulf of Mexico. Image courtesy of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. Download larger version (jpg, 3.3 MB).

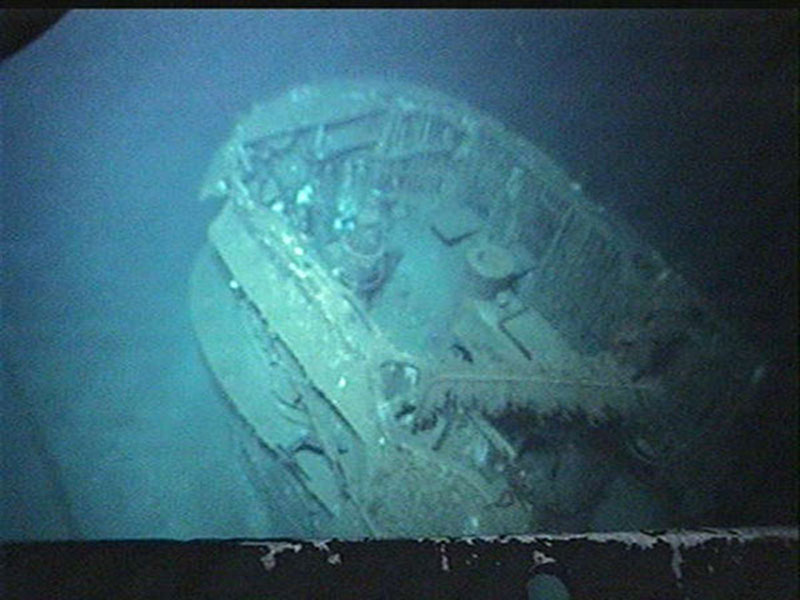

Previous discoveries include several late 19th- to early 20th-century wooden sailing vessels, one of which is thought to be a War of 1812 Privateer. There are also several ships sunk in deep water off the mouth of the Mississippi River by German U-boats during World War II, as well as the only German U-boat sunk in the Gulf by Allied forces, the U-166. Many of these wrecks were not previously known to exist in these areas from historic records.

Recent research on historic shipping routes suggests the historic Spanish trade route leaving from Veracruz, Mexico, for Havana, Cuba, crossed some of the deepest parts of the Gulf of Mexico over 100 miles offshore, which therefore increases the probability that a historic shipwreck could be located in this area. One early Spanish shipwreck is believed to have been discovered in water over a mile deep pending further investigation.

Archaeological Cruise Objectives The archaeological objectives for the present cruise are to investigate, for the first time, several targets found by sonar on oil industry surveys that we strongly feel are historic shipwrecks. Sonar pictures can sometimes be deceiving since using sonar is a bit like trying to figure out what something is by only looking at the shadow it casts. The only way to know for sure is to look at it with you own eyes, or in this case, through the lens of a camera.

View inside the conning tower of the German U-boat U-166. Image courtesy of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. Download image (jpg, 80 KB).

Sometimes something on the sonar can look for all the world like a shipwreck, but turns out to be a natural rock outcrop. Other times something that looks like a pile of junk could actually be a 300-year old shipwreck!

Our mission with Okeanos Explorer will be to try to figure out from the clues we find on the seafloor if the site really is a shipwreck, how old it may be, what it was doing before it sunk, and where it came from. In that sense, archaeologists are a bit like crime scene investigators trying to recreate what happened from what remains. When the crime scene is a shipwreck in water so deep sunlight never reaches it, and the event may have happened over 100 years ago, the case is really, really cold!