By Diva Amon, Deep Sea Biologist - University of Southampton

August 8, 2011

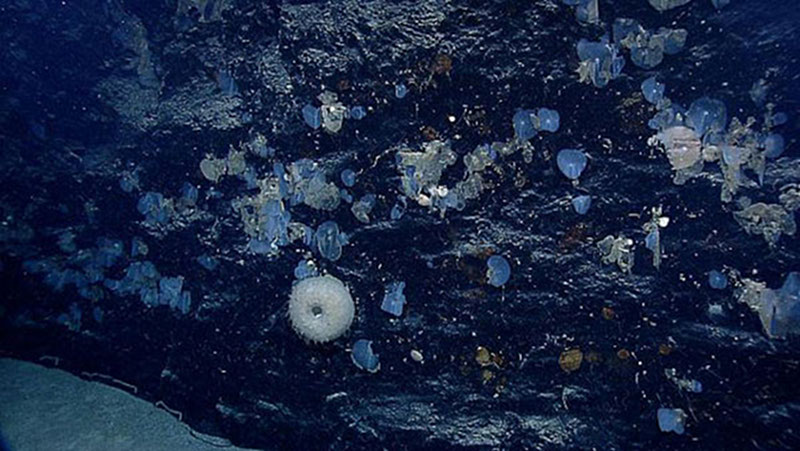

Biological debris that falls from higher in the water column, known as "marine snow" makes up much of the sediment that is deposited on the seafloor. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Mid-Cayman Rise Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 1.6 MB).

During this NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer mission to the Mid-Cayman Rise, we observed biology in three main habitats—sediments, hydrothermal vents and rocky outcrops.

Most of the deep ocean is heavily sedimented and as a result, there are lots of deposit feeders – animals that sift through the sediment looking for food. The sedimented areas in the Mid-Cayman Rise are dominated by large, purple holothurians (Benthodytes sp., Benthothuria sp., and Psychropotes sp.), red shrimp (Sergestes sp.) and tripod fish (Bathypterois sp.). We have also seen various types of rattail fish (family Macrouridae), which are apex predators and scavengers.

A large Gorgonian soft coral juts out horizontally from a rock formation. Each colonial polyp has eight food-catching tentacles, hence the name 'octocoral'. Video courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Mid-Cayman Rise Expedition 2011. Download (mp4, 18.6 MB).

We have also visited some rocky outcrops. This habitat tends to be dominated by gorgonian octocorals such as the bamboo and bubblegum corals (families Isididae and Paragorgiidae), sponges such as the deep-sea siliceous hexactinellids, colonial green stoloniferanand white alcyonian corals, and the occasional anemones and comatulid crinoids. This sedentary fauna is found on rocky areas because they need hard substrata to attach to for stability. They also use the rocky substrata to gain height further up into the water column so that they can have ready access to the current for food. Anemones and comatulid crinoids are also found attached to octocorals as they are then also hoisted away from the seabed, where currents are slowed by the seabed, into more open and freely-flowing water.

A Benthodytes sp. holothurian, or sea cucumber, swimming away from the ROV. Sea cucumbers are commonly found on the deep -sea floor. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Mid-Cayman Rise Expedition 2011. Download image (jpg, 57 KB).

A rocky cliff face with many different types of sponges attached. Sponges are sedentary and attach themselves to rocky areas and filter particles out of the water column. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Mid-Cayman Rise Expedition 2011. Download image (jpg, 104 KB).

By far the most exciting habitat we have seen so far is at the Von Damm hydrothermal vent site. Many of the species seen at this site contain endosymbiotic bacteria that use hydrogen sulphide as an energy source to reduce carbon dioxide and turn it into organic matter—similar to photosynthesis but without sunlight. Fauna found at vents tend to differ between the different areas of the global ocean. This is known as biogeography and scientists are trying to explain these differences by exploring physical, chemical, geological and biological parameters.

The Von Damm vent site is dominated by thousands of shrimp, thought to be of the genus Rimicaris. These shrimp are unique because they have modified appendages inside their carapace, providing a surface for large amounts of chemosynthetic bacteria that use the hydrogen sulphide in the vent fluids as an energy source. The shrimp eat these bacteria as their only known source of nutrition—essentially having a personal farm on their bodies. The shrimp also have a unique ‘dorsal organ’ on the top of their carapace; this is puzzling as the shrimp live in complete darkness in the depths of the ocean. It is speculated that these eyespots may be able to detect thermal radiation given off by the vents and hence help them not to wander too far away from the vent fluid that is essential for their survival.

An abundance of Rimicaris sp. shrimp are clustered around an area of diffuse flow at the Von Damm vent site. These shrimp are about 10 centimeters long and eat chemosynthetic bacteria that are grown on their own bodies. There are also some zoarcid eelpout fish seen among the shrimp. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Mid-Cayman Rise Expedition 2011. Download image (jpg, 126 KB).

A bubble gum coral (Paragorgiidae) with a comatulid crinoid attached. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Mid-Cayman Rise Expedition 2011. Download image (jpg, 79 KB).

Other animals we’ve seen in the immediate vicinity of the Von Damm site include shrimp (an Alvinocaris sp.), white galatheid squat lobsters, white gastropods and zoarcid eelpout fish. Further from the vent site patches of dead Bathymodiolus mussel shells were found, possibly pointing to past areas of diffuse flow.

Before scientific exploration for hydrothermal activity began in the Cayman Rise, there was much speculation about which biogeographic province the fauna would fit into. Some scientists speculated that the fauna were more likely to be similar to the shrimp and mussel aggregations seen at vents along the Mid Atlantic Ridge, which were in close proximity. Other scientists hypothesized that the Cayman vents may have been colonized by vent fauna from the Pacific biogeographic province prior to the closing of the Panama Isthmus around 3.5 million years ago. Based on our initial exploration on the RRS James Cook in April 2010 and further observations during this mission, the Von Damm fauna seems to fit quite well into the Atlantic hydrothermal biogeographic province dominated by shrimp, rather than into the Pacific province, which is dominated by large tubeworms. We are now one step closer to completing the ‘global jigsaw puzzle’ of life at hydrothermal vents.