By Jill McDermott, Chemical Oceanography PhD student - MIT-WHOI Joint Program

August 14, 2011

A white galatheid squat lobster perches upon fractured pillow basalt lava. Generally speaking, galatheids are scavengers found worldwide, but they can be found in high abundance near hydrothermal vents, where food is plentiful. The red laser dots are 10cm apart. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

As the final moments of a dive tick away, the anticipation builds here “on the beach” in the Rhode Island Exploration Command Center—our ROV pilots are on the trail of hydrothermally altered volcanic rocks on Mount Dent. The rocks’ yellow-orange color is in sharp contrast to the dark gray of the surrounding basaltic seafloor lava, and we occasionally spot a bright white squat lobster. This may not sound like a nail biter, as lavas and squat lobsters are found throughout the oceans, but an increasing density in the ‘biological gradient,’ like Hansel and Gretel’s breadcrumbs, may lead us to an active hydrothermal vent and a chemosynthetic ecosystem. I see the magic words “shimmering water!” in our instant messenger log and suddenly it’s right there in the center of the screen, a hot clear plume jetting from seafloor, teeming with squirming shrimp and fluttering bacterial mats.

This rock may be basalt or peridotite, which are both iron-rich rocks. Interaction with a hydrothermal fluid produces yellow-orange iron oxide, also known as rust. There is no shimmering hot water visible now, so the activity must have occurred sometime in the past. This is still a useful scientific observation, since it tells us about the history of the area we are exploring. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

The shimmer effect at this newly discovered hydrothermal vent results from a density contrast between seawater and vent fluid. This density difference is primarily due to a difference in their relative temperatures. This vent does not contain anhydrite (CaSO4), which would be expected to precipitate as a white cloud of mineral ‘smoke’ at 150°C. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 1.7 MB).

Travelling the 2,750 kilometers (more than 1,700 miles) separating us in less than five seconds, the video feed from the ROV Little Hercules opens up the audience to include the University of Rhode Island (URI) shore-based science team, as well as thousands of viewers across the world (hi Mom!). The incredible video footage is just one facet of the exploration process. There are many iterative steps leading up to this discovery.

The "CTD rosette" includes conductivity (salinity), temperature, and depth sensors and a ring of gray Niskin water bottles. The whole array is lowered over the side of the ship on a wire, and the bottles are opened at various depths by sending an electronic signal down the wire. Here Dr. Cameron McIntyre is taking a sample of water from the water column to test for methane. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 1.2 MB).

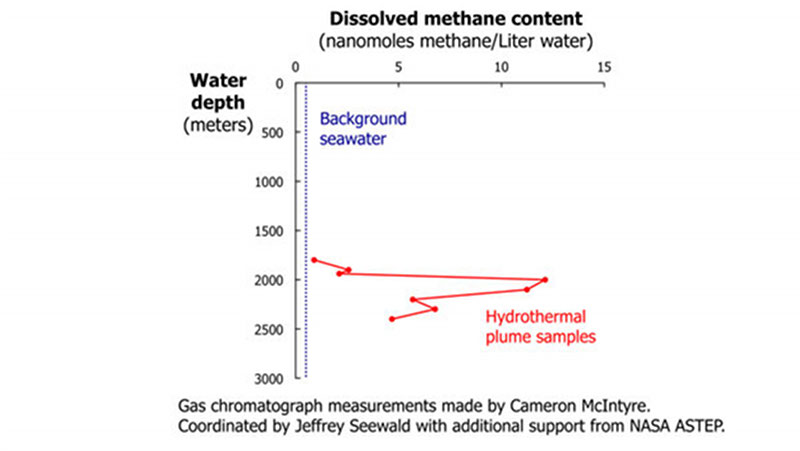

The hydrothermal vents on the seafloor near Von Damm are venting clear hot fluids, and we suspect that they are rich in methane. As this graph from a CTD cast shows, even a mile away laterally from the seafloor vent field, there is a peak in the methane content well above that of regular background water. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, MCR Expedition 2011. Download larger version (jpg, 8.7 MB).

For me, the hunt for vents on Mount Dent began two years ago, collecting water column samples onboard the Cape Hatteras at 10km intervals across the 110km length of the Mid-Cayman Rise. Along with other members of the Seewald lab group from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, I measured the dissolved methane content of the seawater as we searched for reduced water with low oxygen content—a telltale sign of hydrothermal activity on the seafloor. Elevated microbial cell counts and helium-3, a gas left over from the accretion of Earth and an indicator of interaction of hot seawater with deeper crustal and mantle rocks, coincided with the depths at which methane was high, and we sailed home with the certainty that a vent was close.

Dr. Karen Von Damm makes adjustments to the sampling basket on the DSV Alvin, in preparation for a dive following a 2005-2006 eruption on the East Pacific Rise spreading center. Dr. Von Damm is remembered for her seminal research on the processes controlling hydrothermal fluid chemistry, along with her commitment to teaching and advising young scientists. Image courtesy of Jill McDermott. Download larger version (jpg, 13.2 MB).

Several months later, a British-led team collected the first imagery of the vent field on Mount Dent and provided an excellent target for the first dive of this expedition. During this cruise, our night operations have continued to collect methane data and high-resolution multibeam bathymetry to reveal huge faults and smaller volcanic cones in new detail. Here at URI, Drs. Barbara Johns and Michael Cheadle, geologists from the University of Wyoming, lead the analysis of the new map every morning. We line up the faults and volcanic domes in the bathymetry with the bright spots on the backscatter map, to identify places where rocks might be outcropping from the thick sediment draped over the seafloor. Indeed, where there are faults and lavas there may still be fractures and heat, the two key ingredients to sustaining the elusive methane-rich hydrothermal vents.

The new vent field is named ‘Von Damm,’ in memory of Dr. Karen Von Damm, a pioneering deep sea hydrothermal chemist, with whom I did my master’s research. The clear vent fluids here, coupled with the high methane and possibly new biological species, are a unique find, unlike any place I have seen before. As we spiral out exploring for hundreds of meters across this massive hydrothermal field, discovering a new vent even on our last dive within the spreading center, I’m delighted to be working with this team. I can’t help but imagine how thrilled Karen would be.