By Jim Holden, Associate Professor - University of Massachusetts - Amherst

July 20, 2011

The ROV traverses the height of a 10+ meter tall extinct sulfide chimney, covered with smaller chimlets and scavenging galatheid crabs. Video courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, Galapágos Rift Expedition 2011. Download (mp4, 37.7 MB).

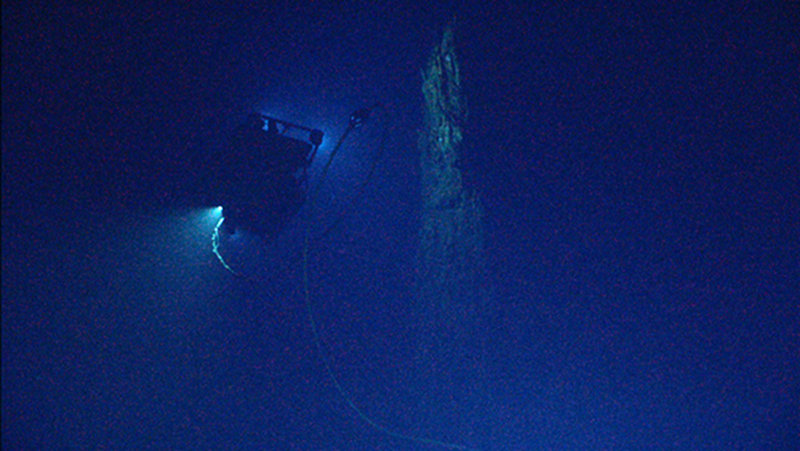

During our third ROV dive on the Galápagos Rift, while searching for active hydrothermal vents, we experienced a strong signal in Seirios’ sonar. As we approached the object in near darkness, the form of a towering hydrothermal sulfide spire appeared, then another, and then another, all lined up west-to-east within the graben (an oblong geologic depression) that we had been following. The spires were up to 23 m (76 ft) tall. However, rather than billowing jets of superheated black fluid and adornment with lush vent animals, these giants laid dormant with only rocky remnants of past black smoker chimneys and scars in the rock where colonies of tubeworms once lived. It was like discovering a once bustling city in the jungle, like Machu Picchu in Peru, that was now ghostly dormant. It must have been a very impressive and vibrant sight at the peak of its activity.

Figure 1. Silhouette of Little Hercules as it approaches extinct hydrothermal sulfide spire along the Galápagos Rift. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 2.3 MB).

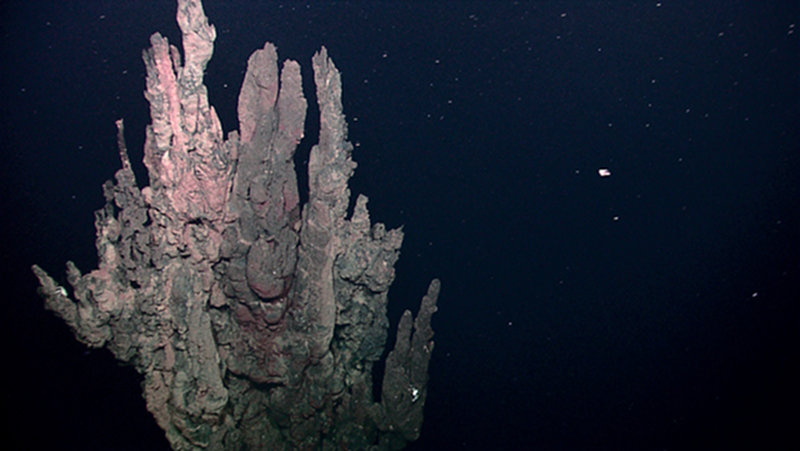

Despite their inactivity, these towering spires tell us a lot about volcanic and hydrothermal activity along the Galápagos Rift. Hydrothermal sulfide chimneys form after hot, metal-laden fluids rise from deep within the Earth’s crust and come into contact with cold, oxygenated seawater. The minerals in the hydrothermal fluids precipitate out forming the characteristic ‘black smokers’ seen at hydrothermal vents around the world. They also form mineral deposits on the seafloor with steep temperature gradients ranging from more than 300°C (570°F) in their interior to 2°C (36°F) on their outer surfaces. Microbes called ‘hyperthermophiles’ that can live up to 122°C (252°F) colonize the inner pores of these deposits, and other microbes and animals colonize the outer surfaces. The microbes are nourished by the mixture of reduced chemicals from the Earth’s crust and oxygen from the seawater that in turn serve as food for the animals. At the Galápagos Rift, these animals include the famous giant tubeworms and clams.

Figure 2. Inactive sulfide chimneys along the pinnacle of one tall extinct sulfide spire. It is likely that these once had billows of superheated hydrothermal fluid emanating from them. They form when minerals in the hot fluid precipitate out upon contact with seawater. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

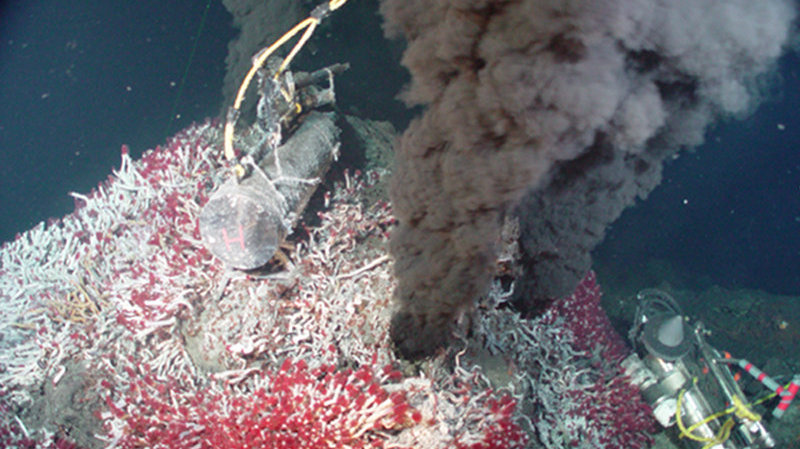

Figure 3. Tubeworms and black smokers from the Juan de Fuca Ridge in the northeastern Pacific Ocean gives a sense of what the Galápagos Rift sulfides might have once looked like. The tubeworms along the Juan de Fuca Ridge are a smaller relative of the ones found on the Galápagos Rift. Image courtesy of NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 3.5 MB).

Hydrothermal spires this tall take several years, even decades, to form suggesting that there was once a large heat source below the surface that took a long time to cool and led to the formation of these structures. Scientists have yet to discover high temperature hydrothermal vents along the eastern half of the Galápagos Rift, but hydrothermal chimneys such as these tell us that there are periods when high temperature venting occurs here. In time though, the seawater that circulates through the crust and interacts with the hot rocks formed by an eruption cools the rock to the point that the high temperature venting ceases. This boom-and-bust cycle is the nature of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Some vents appear to last centuries, maybe even millennia, while others may only last for a year. The vent microbes and animals, nomads of the deep sea, have found ways to move from vent to vent as old hydrothermal systems die off and new ones form. Such is the life of a hydrothermal vent.