By Michael Ford - NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service,

and Miriam Goldstein - Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego

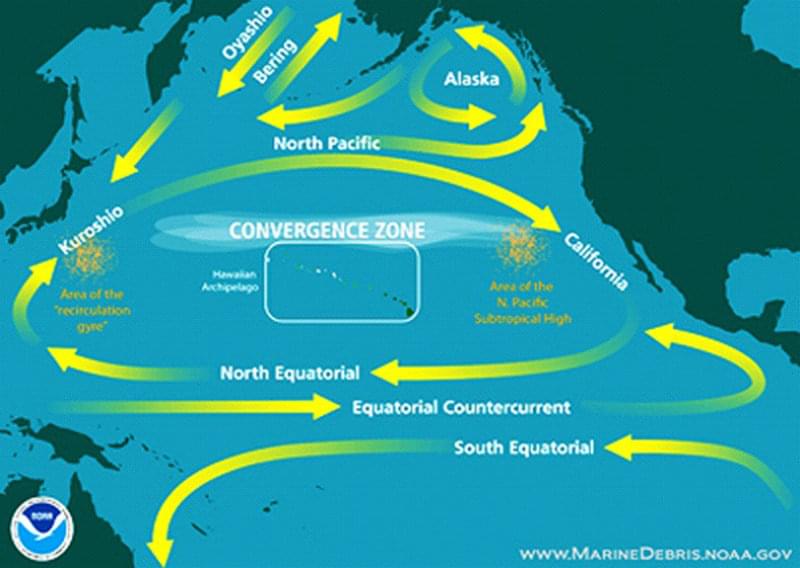

Map of the North Pacific Ocean showing (oversimplified) ocean currents and features. These systems have helped concentrate marine debris, especially large quantities of small bits of plastic, in certain areas.

NOTE: This map is an over-simplification of ocean currents and features in the Pacific Ocean. There are numerous factors that affect the location, size, and strength of all of these features throughout the year, including seasonality and El Nino/La Nina. Depicting that on a static map is very difficult. Image courtesy of NOAA Marine Debris Program. Download larger version (jpg, 127 KB).

The NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer will be passing through the Pacific Ocean “Garbage Patch,” an area in the North Pacific Ocean containing high marine debris concentration. Most of the debris is thought to be small plastic pieces, not always visible to the naked eye. The exact size of this area is hard to pin down because so few oceanographic cruises have crossed this area with an objective to systematically sample plastics – and ocean features are a moving target. The Okeanos Explorer and a team of researchers including scientists from the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service and Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego are collecting small plastic debris and sailing across the breadth of the “Garbage Patch” to get a better handle on the size and composition of this feature. The area thought to contain the most plastic is a thousand miles from land and you can’t see it from space or an aircraft. Therefore, the only way to get there and deploy scientific instrumentation is to use research vessels like the Okeanos Explorer.

Plastic debris was detected in the North Atlantic and the North Pacific in the early 1970s. Since then many organizations have worked on pelagic plastic debris – sampling and regularly visiting these areas of the ocean. However, there is still relatively little data on the location, density, and area of the feature in the Pacific, as well as what impact it might have on marine life. The current mission onboard the Okeanos Explorer will make a substantial contribution to what is known about plastic in the Pacific.

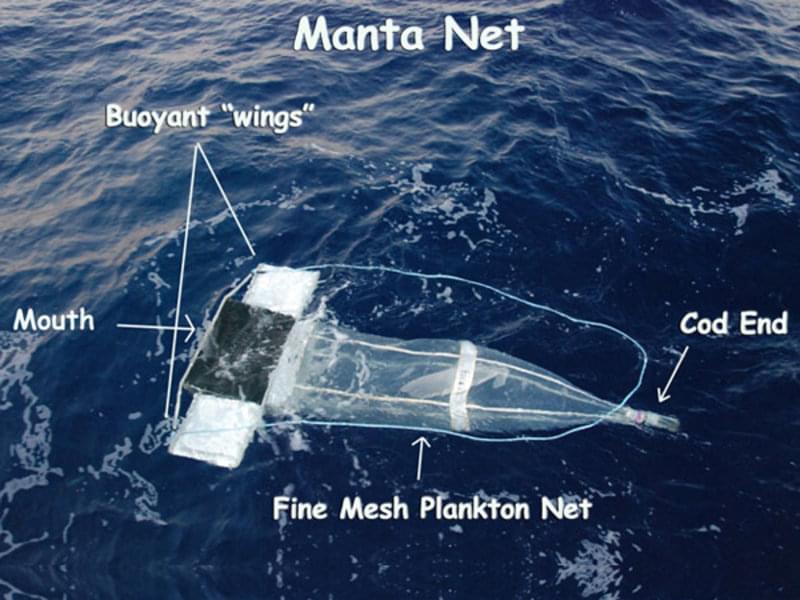

Diagram of a manta net. Seawater enters the mouth and is filtered through a fine, mesh plankton net. Each tow is 15 minutes long, and filters a surface area equivalent to an Olympic-sized swimming pool, concentrating debris and critters at the “cod end” of the net. Image courtesy of NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program. Download larger version (jpg, 133 KB).

Along the trip from Hawaii to the US West Coast, a manta net (a modification of a neuston net) will be towed off the side of the ship. Each tow is 15 minutes long, and filters a surface area equivalent to an Olympic-sized swimming pool. The manta net has buoyant wings on each side so it will glide half above water and half below water to quantitatively collect debris, plastic particles, and plankton larger than 1/100th of an inch (1/3 of a millimeter).

1/100th of an inch seems very small, but actually about half the zooplankton (microscopic animals) and almost all the phytoplankton (microscopic plants) are too small to be caught by the manta. To collect these miniscule animals and particles of plastic, we are sampling the surface of the water and running it through an even smaller filter (less than 1/1000th of an inch, or 20 micrometers). When we get back to shore we will examine these filters for plastic.

Although much of the debris concentrated in the “garbage patch” is composed of small bits of plastic not immediately visible to the naked eye, large items are occasionally observed. On Aug. 11, Scripps Institution of Oceanography SEAPLEX researchers encountered this large ghost net with tangled rope, net, plastic, and various biological organisms. Image courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Download larger version (jpg, 113 KB).

Once in the laboratory back at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and UC San Diego, plastic particles will be sized and counted to provide information on concentration and distribution of sizes along the breadth of the Pacific Ocean “Garbage Patch.” The technique developed in Mark Ohman’s lab at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography uses Zooscan, a specialized type of digital scanner, to take photos of each plastic particle in order to count and measure them. We will also look at the chemical structure of some of the particles to determine the type of plastic of which they are made.

Specialized instruments will have to be used to help quantify the smallest of particles. These may find themselves in the guts of plankton. The degree to which plankton are consuming the plastic particles is an important question and contributes to an understanding of the impact of plastic entering the marine food web, which could include human consumption.

North Pacific Ocean Gyre collections from Scripps Institution of Oceanography scientists aboard the SEAPLEX voyage in August of 2009 revealed small jellyfish (Velella velella) with lots of plastic. Image courtesy of J. Leichter, Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Download image (jpg, 123 KB).

Two lanternfish were collected along with several bits of plastic during the Scripps Institution of Oceanography SEAPLEX voyage. Image courtesy of J. Leichter, Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Download image (jpg, 119 KB).

Plastics and their chemical components are contaminants, but they also contain toxic substances that adhere to their surfaces. To investigate the chemical toxicity of the plastic particles collected on this cruise, some samples along the Pacific Ocean “Garbage Patch” will be immediately frozen for contaminant analysis at the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Northwest Fisheries Science Center in Seattle, WA. There, the particles will be tested for legacy contaminants like PCBs, DDT, and chlorinated pesticides as well as contemporary toxins like BPA, PBPE, and endocrine disruptors. These analyses will provide information about the potential toxicity of the particles present in the Pacific, and ultimately a substance that can contaminate and/or be ingested by fish and other ocean life.