by Martha Nizinski, NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Systematics Laboratory/Smithsonian Institution

Orange brisingid sea stars (Freyella sp.) are common on sedimented rock at 1,703 meters in southwestern Tom's Canyon. Image courtesy of Nizinski et al. NOAA/NMFS/NEFSC, WHOI 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 7.9 MB).

The 2012 Atlantic Canyons Undersea Mapping Expeditions (ACUMEN) field efforts finished with a deep-sea coral survey cruise aboard NOAA Fisheries Survey Vessel Henry B. Bigelow.

After first spending a few extra days at the dock due to ship mechanical problems, we set sail on July 6, 2012, from Newport, Rhode Island, en route to our first priority area for sampling, Toms Canyon complex. Our team, consisting of biological oceanographers, taxonomists, modelers, physical scientists, and a teacher at sea, brought a variety of skills, knowledge, and perspectives that helped us reach our specific objectives.

Our overall goal was to survey and ground-truth known or suspected deep-sea coral habitats associated with deepwater canyons off the coast of the northeastern U.S. In particular, we wanted to survey canyon areas using a towed camera system to characterize benthic (bottom) habitats and identify areas where corals are present; ground-truth areas predicted to be coral hotspots based on data provided from a habitat suitability model; ground-truth newly collected multibeam data; and ground-truth historical coral records.

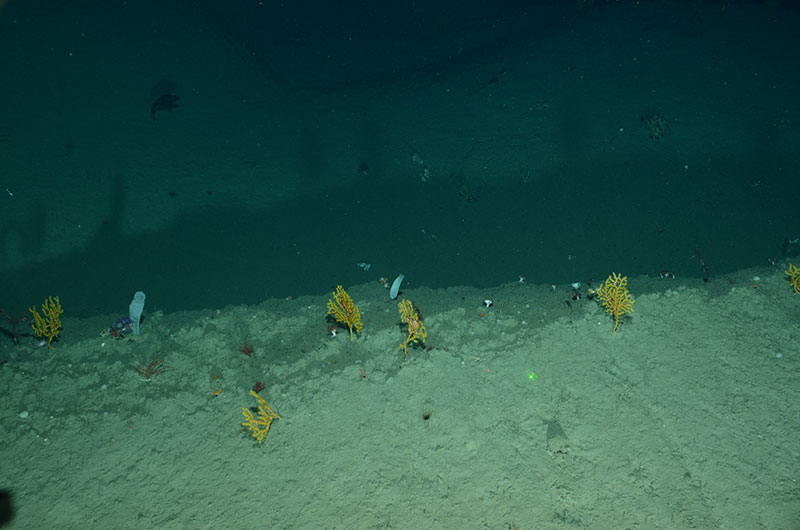

Several small red corals (Anthomastus sp.), yellow corals (Paramuricea sp.) with brittle star associates, and two white vase sponges are just a few of the organisms captured in this image taken at 1,419 meters in Veatch Canyon. Image courtesy of Nizinski et al. NOAA/NMFS/NEFSC, WHOI 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 7.1 MB).

We used a variety of tools to guide our sampling during this expedition. First, high-quality multibeam data, hot off recent ACUMEN expeditions by NOAA Ships Okeanos Explorer and Ferdinand Hassler, helped us locate interesting bottom features that appeared to be likely coral habitat. We then consulted results from our recently developed habitat suitability model. This model uses various physical and biological data to predict where corals are likely to occur based on conditions found in locations where corals were previously reported. We also plotted historical records – some collected over 100 years ago – to help guide our sampling.

Next, we compared areas identified by our habitat suitability model as potential coral hotspots to the multibeam data. Areas where potential hard bottom and potential coral hotspots overlapped were selected as our primary sampling targets.

A field of yellow Paramuricea sp. corals and a sea star observed at 1,679 meters in Gilbert Canyon. Image courtesy of Nizinski et al. NOAA/NMFS/NEFSC, WHOI 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 8.6 MB).

Now was the moment of truth. Would we find corals in these areas?

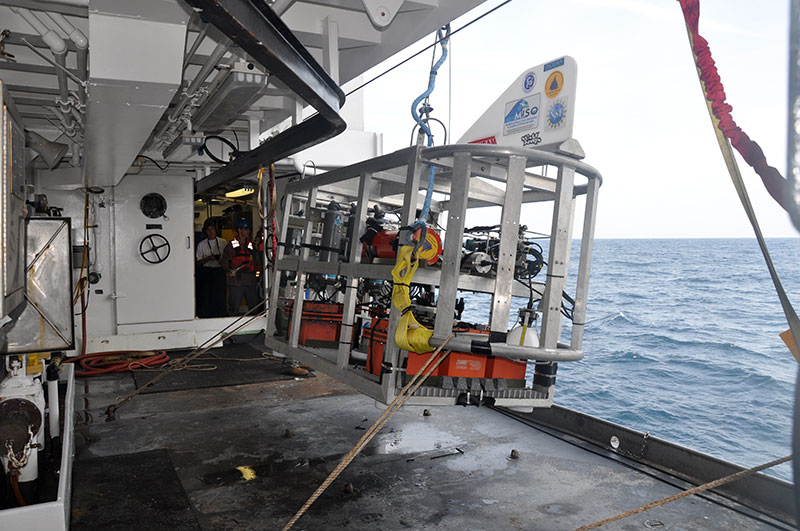

The crew prepares TowCam for deployment. Image courtesy of T. Heyl 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 7.6 MB).

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s TowCam, our “eye in the sea,” lifts off the deck during deployment on the first dive of the cruise. Image courtesy of T. Heyl 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 6.2 MB).

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s towed camera system (TowCam)was our eye in the sea during the Bigelow cruise. Careful coordination between the ship and TowCam pilots was necessary to ensure that the camera followed the course we set for the survey and did not hit any obstructions during surveys. Constant communication between TowCam operations in the dry lab and the bridge made sure that everyone was on the same page in guiding the camera through the water, about three meters from the bottom. This type of coordination during the dive was necessary to ensure we had a successful survey and that we were able to collect the best data possible.

TowCam provided us with high-resolution images of the bottom, in real time, that allowed us to determine whether corals were present as well as to assess and characterize habitats within the canyons. On a typical dive, TowCam was in the water for seven to eight hours, taking pictures every five seconds. That’s a lot of pictures!

Our days revolved around TowCam operations. Since this was our primary sampling gear, we wanted to maximize the amount of time the camera was in the water. So, we maintained a steady stream of TowCam operations throughout the cruise. Approximately four hours were needed between deployments to charge batteries (both camera and crew!), download photos, and perform any camera maintenance that was needed.

In total, we conducted 18 TowCam surveys, which provided approximately 107 hours of bottom time and over 38,000 photographs.

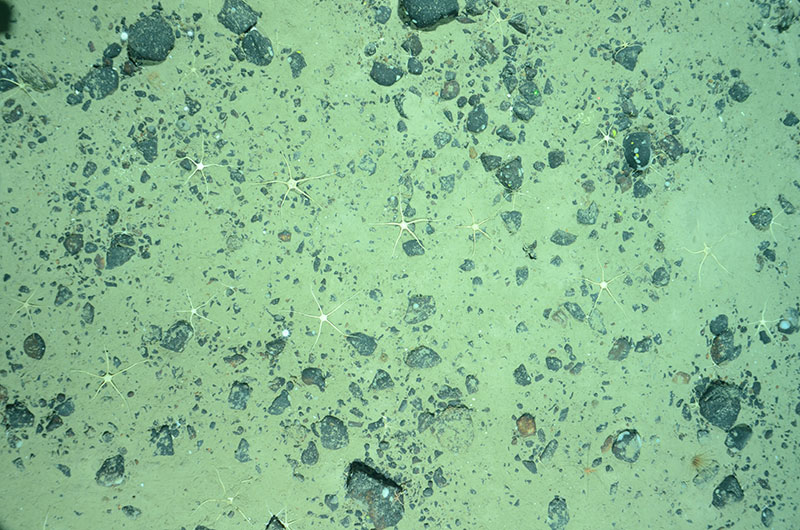

Many brittle stars scattered over pebbled sediment at 1,965 meters in Gilbert Canyon. Image courtesy of Nizinski et al. NOAA/NMFS/NEFSC, WHOI 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 7.8 MB).

We targeted three main areas: Toms Canyon complex (with tows in Toms, Middle Toms, and Henderickson Canyons), Veatch Canyon, and Gilbert Canyon.

Our first tow, the shake down tow, was conducted in a fairly flat, soft bottom area so everyone could get used to TowCam operations, especially deployment and recovery of the system. Also, in this area, there was less likelihood that the camera could be damaged during the tow if something went wrong. But even in this area, where our expectations were low, we were able to get a feel for what was in store for us over the next 12 days. Here, we were fortunate to observe some animals of interest that prefer soft sediments.

Our fourth tow in Henderickson Canyon provided images of bubblegum coral! We were off to a great start. We made six dives total in this area and were successful in finding a variety of gorgonians, sea pens, and sponges.

Next stop was Veatch Canyon, where we made four dives. Here, we found paramuricid corals in high abundances as well as an abundance of a solitary hard coral (most likely Desmophyllum dianthus) and a variety of sponges living on the steep canyon walls.

Our final destination was Gilbert Canyon, where little was known about this particular canyon and which the model had predicted to be a coral hotspot. Within minutes of TowCam reaching the bottom, we knew that the model prediction was correct. Coral diversity and abundance was high. Not only did we find coral species similar to what we had observed in the other canyons we surveyed, but we also observed black corals. Black corals were not previously recorded from this area. The remaining seven dives in this area continued to produce fantastic data and images of corals and sponges.

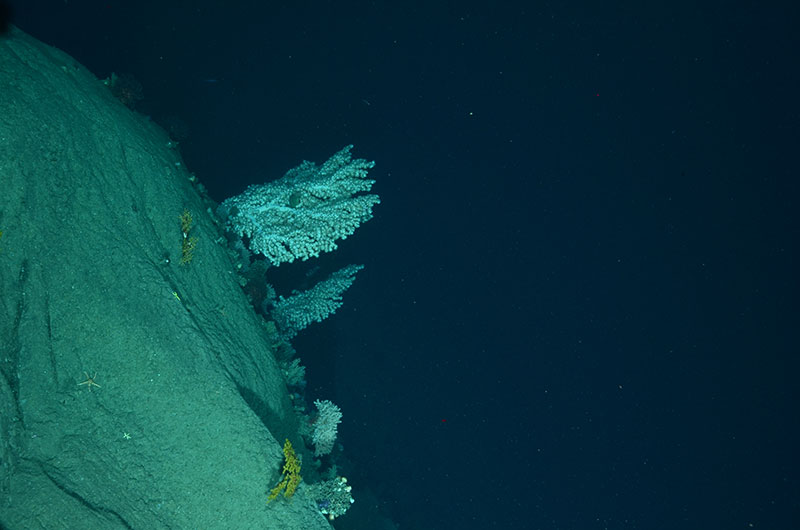

Large bubblegum corals (top center image) and smaller octocorals, yellow Paramuricea sp., observed at 1,221 meters in Gilbert Canyon. Image courtesy of Nizinski et al. NOAA/NMFS/NEFSC, WHOI 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 7.0 MB).

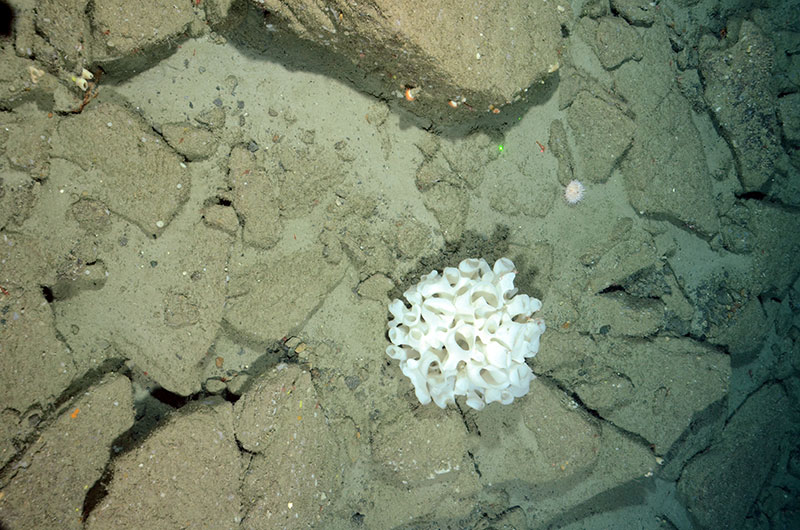

A white sponge approximately, 60 centimeters in length, is hosting two shrimp. Multiple smaller sponges, anemones, and urchins were also observed at this rock, cobble, and sedimented habitat at 820 meters depth in Gilbert Canyon. Image courtesy of Nizinski et al. NOAA/NMFS/NEFSC, WHOI 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 10.0 MB).

This mission was a huge success. In the relatively few days we were at sea, our knowledge of deep-sea coral diversity and distribution in the Northeast region has increased exponentially. We qualitatively validated our deep-sea coral habitat suitability model; the model correctly predicted suitable coral habitat and identified hotspot of coral abundance and diversity like Gilbert Canyon. Deep-sea coral habitat was matched to high-resolution bathymetry maps through ground-truthing of bottom topography. Antipatharians (black corals) were discovered in Gilbert Canyon.

To effectively manage and conserve marine habitats and the species that live within them, we must first understand the distribution and extent of habitats and we need to have a good working knowledge of the diversity and composition of the species assemblages that occur within these habitats. Data collected on this cruise will guide future sampling missions as well as provide information to fishery management councils as they develop recommendations to conserve deepwater coral habitats off the northeastern United States.

Photographs will be processed and analyzed over the next several months and we will begin to analyze these data and evaluate our findings. This was an extremely productive field season, but much more work still needs to be done. Believe it or not we are already preparing for next year’s research activities!

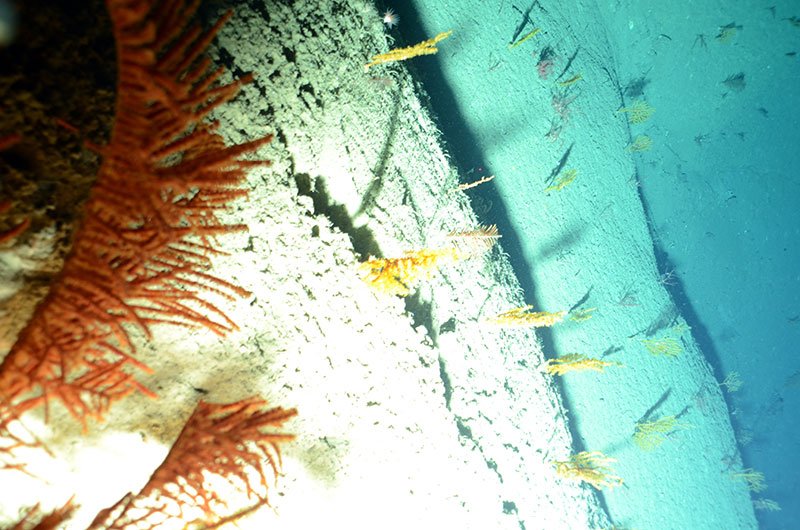

A close up of black coral (Bathypathes sp.), multiple yellow (Paramuricea sp.), and red (top right of image; Swiftia sp.) corals as TowCam came very close to this scarp at 1,679 meters in Gilbert Canyon. Image courtesy of Nizinski et al. NOAA/NMFS/NEFSC, WHOI 2012. Download larger version (jpg, 7.3 MB).