by Martha Nizinski, Zoologist, National Systematics Laboratory, NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center

Practically every deep-sea expedition provides something new, interesting, and important to learn about. This single collection from a suction sampler includes several different types of deep coral. Image courtesy of Art Howard, Life on the Edge, NOAA Ocean Exploration. Download image (jpg, 90 KB).

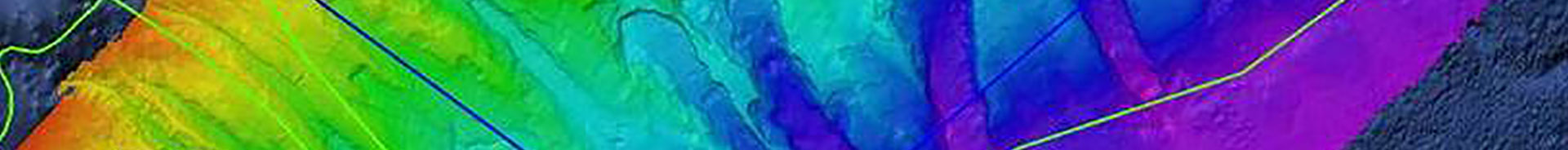

Deepwater canyons are prominent features off the coast of the eastern United States, beginning at the edge of the continental shelf and with some extending down the continental slope to the abyssal plain. Over 70 named canyons of various sizes have been discovered in this region, ranging from large, deeply incised canyons that can be thousands of meters deep to smaller, shallower canyons of less than 1,000 meters. Extent, depth and overall shape of any particular canyon are dependent on the processes that formed the canyon. For example, some canyons are drowned ancient riverbeds, while others are formed by underwater landslides.

The topography, currents and sedimentation in and around submarine canyons can be quite complex. Canyons may have steep-sided walls and exposed ridges, rocky outcrops and/or gentle slopes. Morphology of the seafloor affects the strength and direction of bottom currents and the downslope movement of sediment particles. Soft sediments transported off the continental shelf may settle in these canyons also.

Martha Nizinski examines a deepwater coral specimen collected off the southeastern U.S. Image courtesy of Art Howard, Life on the Edge, NOAA Ocean Exploration. Download image (jpg, 156 KB).

Canyons tend to be biodiversity “hotspots” compared to adjacent habitats and often support higher biomass of organisms than other deep-sea habitats, likely due to the complexity of the habitat. Unlike other deep-sea habitats, diversity within submarine canyons tends to increase with depth. Additionally, the fauna found in canyons is often different from that found in adjacent soft-bottom habitats.

Of particular interest to the Atlantic Canyons Undersea Mapping Expeditions (ACUMEN) project is the occurrence of deep-sea corals in these canyons. Strong water currents and movement of water masses around the canyons sweep away finer sediments and expose the hard surfaces underlying these finer sediments. These exposed surfaces provide ideal habitats for larvae of deep-sea corals to settle and attach to the bottom. Coral larvae may also settle on the steep canyon walls or other hard surfaces such as boulders that may have tumbled into the canyon.

Strong currents also provide a steady food supply to the growing corals. Thus, conditions within submarine canyons seem to favor both development of coral habitats and coral growth once they are established.

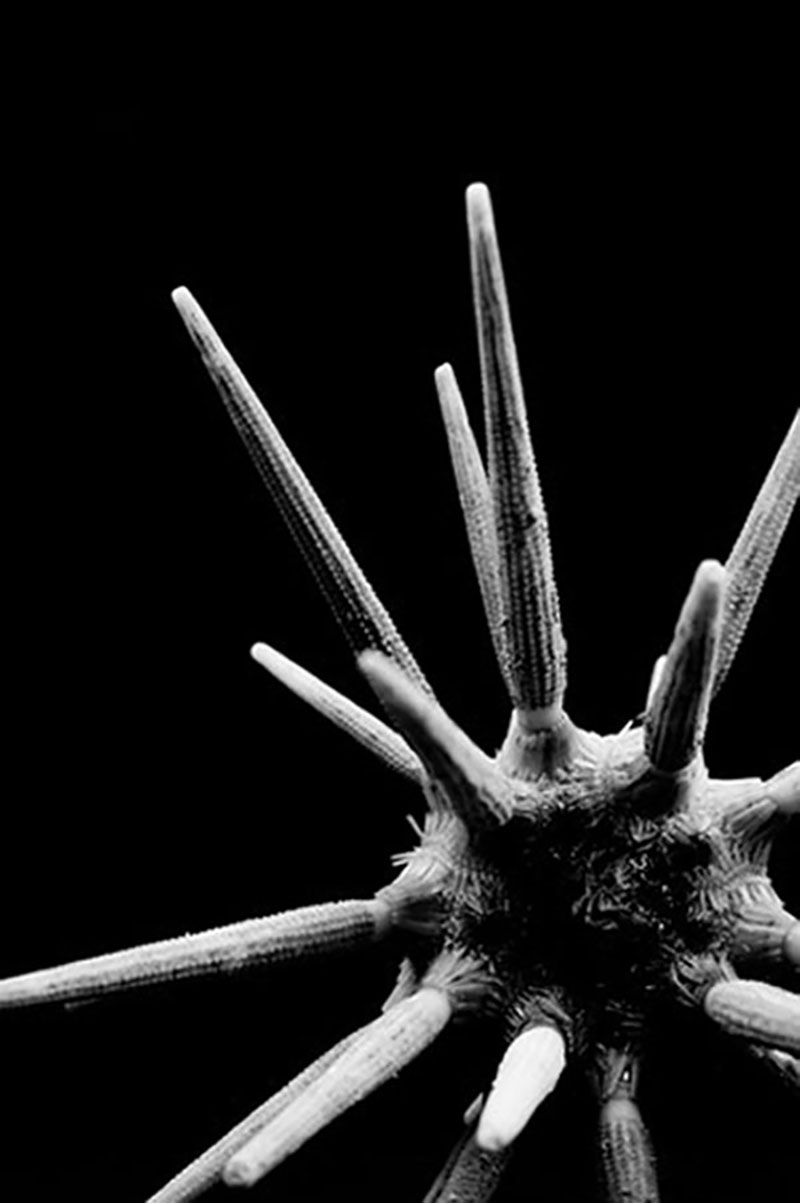

These coral colonies also provide structure and habitat for other organisms. Crabs, shrimps, anemones, brittle stars, fishes, and other corals are some of the animals found in deepwater coral habitats.

Coral colonies provide structure and habitat for other organisms. Urchins are just one of the many animals found in association with deepwater coral. Image courtesy of Art Howard, Life on the Edge, NOAA Ocean Exploration. Download image (jpg, 67 KB).

Commercially and recreationally important fish and crustacean species, associated either with the corals or with the canyon heads, also occur in these habitats, sometimes occurring in much higher abundance there than in other deep-sea habitats. Coral habitats, therefore, may be at risk within canyon areas because they can be damaged during fishing activities conducted in these areas.