by Meredith Meyers, NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer Student Mapping Intern, McDaniel College

Intern Meredith Myers and marine ecologist Dave Packer viewing canyon data using Fledermaus software in the Okeanos Explorer control room. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download larger version (jpg, 526 KB).

It is often said that we know more about the surface of the moon than we know about the surface of the seafloor. After serving as an intern aboard the Okeanos Explorer during the ship’s second cruise as part of the Atlantic Canyons Undersea Mapping Expeditions project, it is hard to argue with this comparison. It is impossible to grasp the sheer expanse of the oceans until you have spent time on the water, far away from shore.

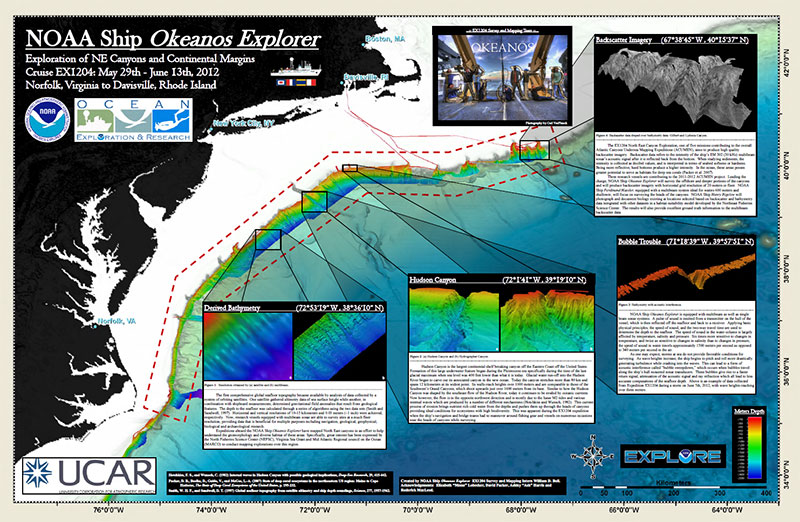

As a recent college graduate with a degree in environmental biology, I pictured this internship as the perfect opportunity to expand my field skills. With a degree in biology and hopes of pursuing marine biology and policy in graduate school, I was eager to acquire experience in the field of oceanography. Through the use of multibeam sonar technology and the accompanying backscatter data, we are able to create images detailing the topography of the seafloor. The priority areas being surveyed for this expedition are deep water canyons that lie along the continental shelf, from the Mid-Atlantic states to as far north as Massachusetts.

This poster shows the locations and provides information about the areas that were mapped during the second Atlantic Canyons Undersea Mapping expedition. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. Download poster (pdf, 1.4 MB).

Ocean exploration holds the key to our ability to better understand and manage issues such as climate change, natural resource use, geological processes, and marine species conservation. Being a biologist, I am interested in how the data we collect during this expedition can be applied to species conservation and the development of marine policy.

Lucky for me, a member of the science team, David Packer, is using the data in order to identify deep-sea coral habitat. He hopes that the identification of prime coral habitat will expedite plans for legislation in order to protect these areas and ensure healthy coral populations in years to come. It is known that deep-sea corals prefer hard substrate and deep depths, so Packer predicts that the deep-water canyons we are surveying would serve as prime habitat. I sat down with Packer in order to better understand his mission for this expedition.

Question 1: As a marine ecologist, which agency do you work for, and what is its purpose?

Answer: I work for NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC). The agency manages the nation’s federal marine fish stocks and their habitats. The Northeast Fisheries Science Center is essentially the northeast and mid-Atlantic’s research arm of the National Marine Fisheries Service – we have six laboratories in the region.

Question 2: How did you obtain your position at NEFSC? Does the job reflect what you studied during your academic career?

Answer: I received my undergraduate degree in zoology from Ohio State University. Before graduate school, I held many part-time jobs with the federal government. For instance, I volunteered and worked for the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management. I also volunteered at the Smithsonian Institution’s Marine Systems Laboratory. The latter helped me to get into graduate school at the University of Maine where I received my Masters degree in oceanography.

After grad school, I was an intern with the Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program in Annapolis, Maryland. While I was interning, I applied for and received a full-time position at NEFSC’s James J. Howard Marine Sciences Laboratory in Highlands, New Jersey, as a marine ecologist. And the rest is history.

Question 3: Did you have any ocean floor mapping experience, or experience using multibeam sonar, before this cruise?

Answer: I never had true hands-on experience with this type of sonar technology in the field. However, I took a marine geography course in graduate school, and I had experience working with geologists before and during graduate school. Essentially, I understood the concept and the lingo, but had never experimented with the actual technology.

Question 4: How did you become involved with this Okeanos Explorer expedition?

Answer: My colleague at the Smithsonian Institution, Martha Nizinski, and I are currently working on deep-sea coral research off the northeastern United States. Several months before this cruise we started having discussions with Jeremy Potter from the Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, and the expedition manager for this cruise, about collaborating and doing opportunistic mapping surveys using the Okeanos Explorer.

The focus would be in mapping the submarine canyons on the edge of the continental shelf and slope. Deep-sea corals are found in many of these canyons, but we know very little about their habitats, or even if they’re present or how many there are. The first step is to get accurate bathymetric maps, so we gave Potter and his colleagues our priority areas for mapping. But first, in order to learn more about their program, Potter invited me to visit the University of Rhode Island’s Inner Space Center, where I got a good introduction as to how Okeanos Explorer operates and the technology involved. I then volunteered to go on one of the Okeanos cruises, and was assigned to participate in this expedition, where many of our priority canyon areas were set to be surveyed.

Question 5: Why do you feel it is important to map deep-sea coral habitat?

Answer: At the present time, there is very little information available to be able to predict, and ultimately know, where to find these deep-sea corals. Most of the information we have on deep-sea coral location is decades old and often little is known about these submarine canyons, which is where we are focusing our mapping for this expedition. Deep-sea corals may serve as critical habitat for many fish species and other invertebrates and contribute to overall biodiversity in these areas. We predict that these corals are found mostly on hard substrate. Therefore, by mapping the seafloor and determining substrate components, we can make predictions as to where we might find them. NOAA has a mandate which serves to protect deep-coral habitats. By obtaining this seafloor mapping data, we hope to assist in the development of management plans.

Question 6: From the data that we have obtained and processed so far, are you happy with what you are seeing? In other words, are we successful thus far?

Answer: The data that we have sorted through already looks fantastic! We originally thought that we would be receiving bathymetric data. Turns out we are also able to receive backscatter data. Backscatter is simply the value of the amplitude of return of the signal. When a sound wave bounces off the seafloor, it then returns to the transducer on the hull of the vessel. Essentially, the harder the substrate is, the greater the returning amplitude. This backscatter data provides evidence of where corals may be found. We can couple the backscatter with bathymetric data, and then check that data against our predictive habitat suitability models that we are developing to predict possible coral habitat.

Question 6: Once all the data is collected, how do you plan on using it?

Answer: Not only do we plan on using this data for our own upcoming, major deep-sea coral research efforts, we also plan to share the data with the New England and Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Councils. These data will assist the Councils in developing a deep-sea coral management plan that will protect the corals and their habitat.

Question 7: Are there any other areas around the world that you would like to map or feel should be mapped?

Answer: Since the agency I work for is based in the New England/Mid-Atlantic region, my sights are fixed on continuing to map the Atlantic along the East Coast. There are four seamounts way off the coast of New England that are biodiversity hotspots for corals and other invertebrates. Two were sampled on a previous expedition several years ago. I’m sure the other two are also prime deep-sea coral habitat. We are due to receive funding from NOAA’s Deep-Sea Coral Research and Technology Program for a three-year deep-sea coral research program. Hopefully, we’ll then be able sample and map those two other seamounts that were missed and to continue mapping additional submarine canyons along the East Coast.