Voyage to the Ridge 2022

May 14 - September 2, 2022

The Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone: A Jewel in the Mission Blue Crown

In May, NOAA Ocean Exploration completed the largest continuous mapping survey effort to date over the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone, collecting bathymetric data along this geologically fascinating and ecologically exceptional region. In June, Mission Blue re-launched the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone Hope Spot. In this essay, Hope Spot Champion Professor David Johnson relays what makes this deep-sea fracture zone and the life found within it so unique and worth discovering, understanding, and protecting.

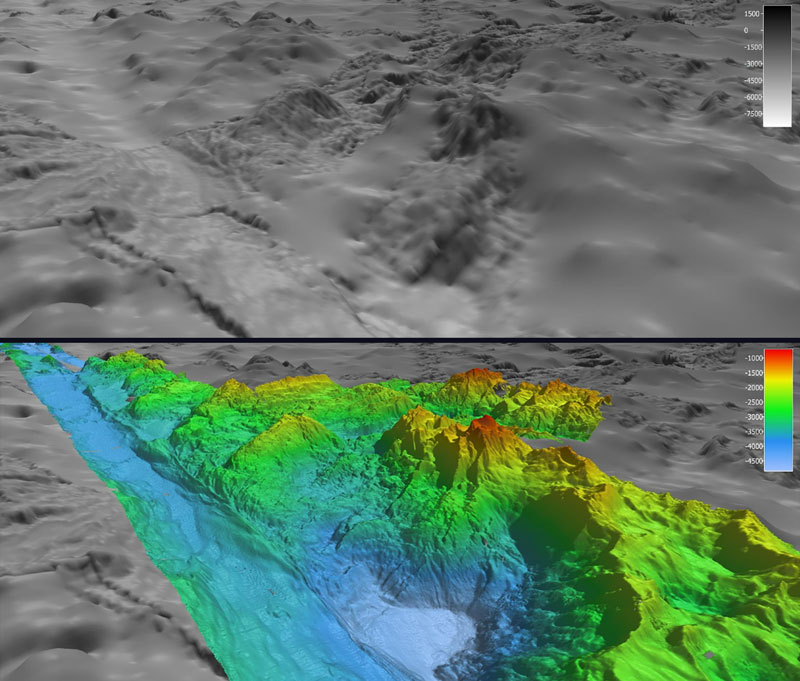

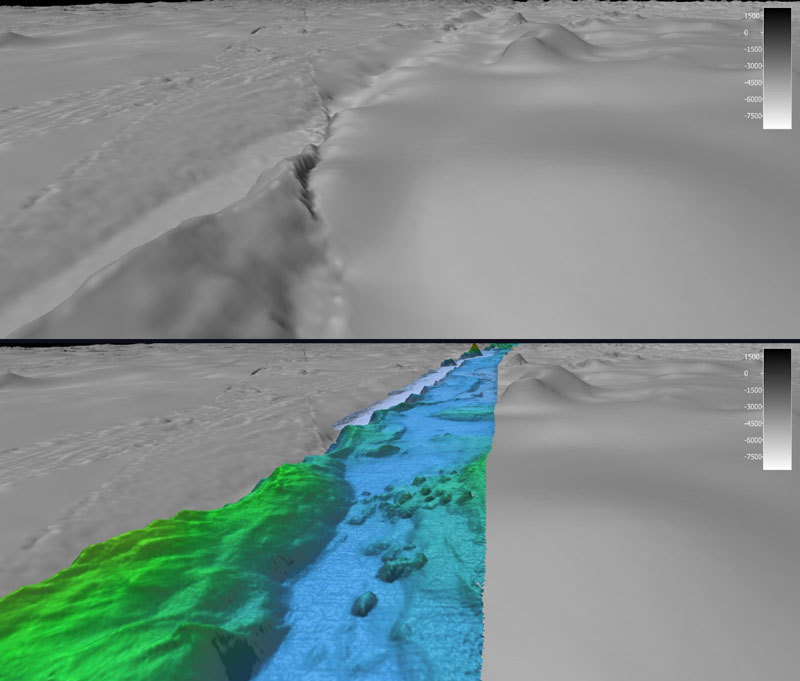

The Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone is a unique geological feature. Fracture zones are effectively scars in the lithospheric plates of the ocean floor extending from transform faults at an active plate boundary. In the case of the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone, the active boundary is the diverging spreading center of the north-south trending (or oriented) Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and the transform fault creates a more than 300-kilometer (186-mile) offset of the rift valleys to the north and south. To add to the complexity, the fracture zone actually comprises two parallel transform faults – the Charlie and the Gibbs – that have interesting tectonic interactions.

The varied topography (ranging in depth from 700 – 4,500 meters/2,297 - 14,764 feet), nutrient-rich water mass exchange, vertical mixing, and meandering currents surrounding the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone combine to create an amazing combination of diverse and biologically productive deep-sea ecosystems. It is a deep-sea researcher’s treasure trove!

And it’s massive! The Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone is one of the deepest connections between the northwest and northeast Atlantic and extends approximately 2,000 kilometers (1,243 miles) in length. If you take a transatlantic flight from New York to London, the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone appears on the moving map! It is the most prominent interruption of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between the Azores and Iceland and the only fracture zone between North America and Europe that has an offset of this size.

This unusual fracture zone is not named after a person. Instead, its namesake comes from Charlie, a mid-Atlantic weather station, and U.S. Naval Ship Joshua Willard Gibbs, a research vessel. The feature was discovered in 1966 on a trans-Atlantic oceanographic survey mission undertaken by U.S. Coast Guard cutter Spar (WLB-403) and has inspired deep-sea scientists ever since.

A Mission Blue Hope Spot

A fundamental principle of the non-governmental organization Mission Blue is that a healthy ocean begins with awareness and creating a global wave of community support for ocean conservation. Led by legendary oceanographer Dr. Sylvia Earle, the organization has established more than 140 Mission Blue Hope Spots. These are special places that are scientifically identified as critical to the health of the ocean. The Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone was among the first Mission Blue Hope Spots and encompasses the fracture zone, the meandering Sub-polar Frontal Zone, and diverse communities of junctions with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, including individual seamounts.

This June, the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone Hope Spot was re-launched, confirming my role as the new Hope Spot Champion . I have a strong connection with the area. In 2010, as Executive Secretary to the OSPAR Commission , I was instrumental in persuading ministers to declare the area as one of the world’s first High Seas marine protected areas. Since then, I have worked as coordinator of the Global Ocean Biodiversity Initiative , working with the Convention on Biological Diversity to highlight special places in the ocean and work to conserve their integrity. Charlie-Gibbs has stayed on my radar!

To make a difference, I have set three interconnected Mission Blue Hope Spot objectives. First is to know more. The area is a living laboratory, but there is much to explore. In addition to everything that can be found at the seafloor and in the water column, the area is a ‘deep-sea drive-through’ for migratory species – seabirds, whales, turtles and sharks – a safe place for feeding, resting, and reproduction!

Secondly, as a formally protected area, the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone is a refuge for long-lived species and a likely sanctuary from the impacts of climate change. I am keen to help keep it that way, to recognize potential future threats and persuade decision-makers to take action.

And thirdly, the area has all the elements to be an exemplar for ocean governance. The world is finally waking up to the urgent need to safeguard even the deepest and most remote places in the ocean: the final frontier and its vulnerable fauna. More work is needed to gain universal recognition and to bring together all those with an interest in ocean sustainability. Mapping data collected during the first Voyage to the Ridge 2022 expedition provides an essential base map to support further research and understanding of this special deep-ocean habitat.

Great Expectations

In 2010, as part of the Census of Marine Life, the Mid-Atlantic Ridge Ecosystem (MAR-ECO) Project resulted in the observation of mid-water organisms, benthic suspension feeders, and soft sediment benthos. There is evidence of both deep-sea sponge aggregations (demosponges and glass sponges) and cold-water corals in this area.

We are now in the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science . Raising awareness of the importance of deep-sea fracture zones and the life forms they support is exciting and challenging, but increasingly possible. Actionable science requires us to actively discover, understand, and broadly share new knowledge. While the dives initially planned along the Charlie-Gibbs Fracture Zone as part of Voyage to the Ridge 2022 are not going to be possible due to expedition delays, mapping data collected during the first expedition provide us with insights into the region and will also help with planning future expeditions to the region, so we can expand our understanding of this geologically fascinating and ecologically exceptional place.

By David Johnson, Emeritus Professor Solent University UK

Honorary Professor School of GeoSciences University of Edinburgh UK

Published July 18, 2022