by Colleen Peters, Senior Survey Technician

August 5, 2010

Physical Scientist Meme Lobecker teaches Indonesian scientist Cecep Sujana how to conduct an XBT cast. The XBT measures temperature through the water column. The XBT software calculates sound velocity, which is applied to the multibeam data for an accurate measure of bathymetry. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 3.6 MB).

People are easily mesmerized by biology. It moves! It wiggles! It spits! This makes the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) video particularly captivating for a wide audience. In comparison, mapping is perhaps ‘not as entertaining.’ I have to admit, standing a mapping watch through the midnight hours (one of my main duties) is not the most exhilarating activity, but is a key and necessary component of our mission.

Some mapping shifts, containing lines several hours long, can be as involved as watching colors on a screen move slightly with the occasional push of a button or two. There will be days where the two of us will ‘rock-paper-scissors’ for who gets to process data because we are so bored (which is good because that means the system is working well and the data looks good). However, without knowing what the seafloor looks like, we wouldn’t know where to explore with the ROV. Without knowing the contours and depths of an area, we would be flying blind.

Senior Survey Technician Colleen Peters makes an entry in the mapping watch log book. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 4.4 MB).

Typical night-time mapping watch in the control room. Back to front: Senior Survey Technician Elaine Stuart monitors incoming data and adjusts settings as necessary; ROV team member, Tom Kok, does double duty by processing mapping data as it is collected; Major Dian Adrianto provides hourly status updates about ship operations to shore via intercom and the eventlog. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 5.2 MB).

Mapping the seafloor is often referred to as ‘mowing the lawn.’ When you mow your lawn, you do not push or drive your lawn mower around the yard in haphazard squiggly directions, create designs, or write your name in the grass. Typically, you start at one corner of the yard and continue with lines parallel to each other, overlapping the previous pass so as not to leave any stray grass still standing. This pattern continues until the bulk of the yard is sufficiently trimmed. The last step of the cutting process is to remove any loose ends that you couldn’t get on the first go-round, such as areas close to fences or around tree trunks. Once the entire yard is completed, you go back over it to rake up the clumps of grass left behind by the mower so that the lawn looks neat and presentable.

The act of mowing is like the ship conducting the survey. Trimming the grass you couldn’t reach is what happens when our coverage is not sufficient or we experience a problem with the system, leave a holiday (hole in the data) and need to run over it again, in the Okeanos Explorer’s case, to fill it in. Cleaning up the grass clumps is the data processing, where we carefully remove extraneous points, making certain that they are artifacts (false data) and not a real feature of the seafloor (when you mow the lawn and the mower leaves a trail of grass that is parallel to the track of the mower that is an example of an artifact).

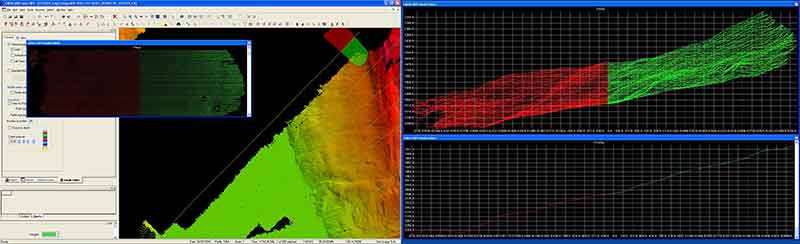

Caris is the main tool used for processing multibeam bathymetry. Shown is the swath editor, where the watch stander can examine the data from various perspectives. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 2.4 MB).

After grabbing a cool glass of lemonade, you might stand back and admire your handiwork. Then, noticing the small flat area facing the morning sun, you consider it a potential spot for an herb garden. You go back to the shed to grab a shovel and go to the new spot and dig a few inches to examine the soil. If the soil is just right, you dig a little deeper for confirmation, then go back to the shed and grab a few more tools, like some peat moss, seeds, and a watering can. You spend the next while digging small holes, inserting the herbs into the fresh earth, and once they are secure and covered, add some water.

On the Okeanos Explorer, we take Frappuccino breaks. Testing the soil for planting is like conducting a CTD—we check to see if there is anything interesting going on within the physical environment. Planting the herbs represents the ROV dive because much like the herbs, the video collected can be reexamined for many years to come. As you would use assorted herbs for seasoning a variety of cuisines, the video can be used for a wide range of scientific disciplines.

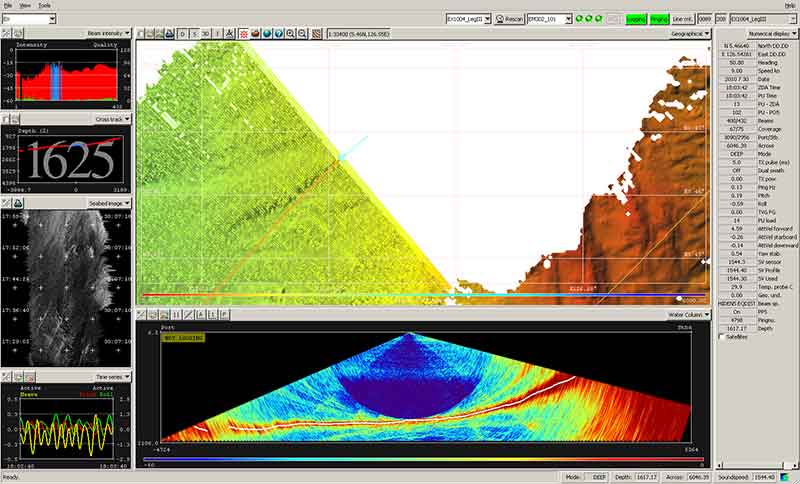

This is a screen grab from the multibeam acquisition computer during a typical mapping watch. The center area shows the coverage, on the left are the sonar signal strength, depth, backscatter and ship motion data. The bottom window is the water column display, where the sonar can also detect features such as plumes. Image courtesy of the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, INDEX-SATAL 2010. Download larger version (jpg, 1.4 MB).

As you pass a live feed or see an image of the control room, nearly barren, save for two watch-standers, eyes glazed and staring ahead, rest assured that they are actually working. Watching the multibeam is a tedious process, but it takes a trained eye to recognize and deal with issues that can and do arise. At the end of the night, maps are updated so that the ROV team and shore-side scientists observing from the Exploration Command Centers can all look at the same dataset to plan CTD casts and ROV dive sites.

We don’t sweat and get dirty like the deck or engine departments. We don’t stand on our feet all watch like the deck officers and lookouts. We sit and watch the multibeam in four- or eight-hour shifts, focusing on minute details, multitasking, and coordinating operations with the bridge and shore. We examine many hours and miles worth of data line by line, each and every ping. It’s a tough job, but someone’s gotta do it.