by Professor James F. Holden, Ph.D., Department of Microbiology, University of Massachusetts at Amherst

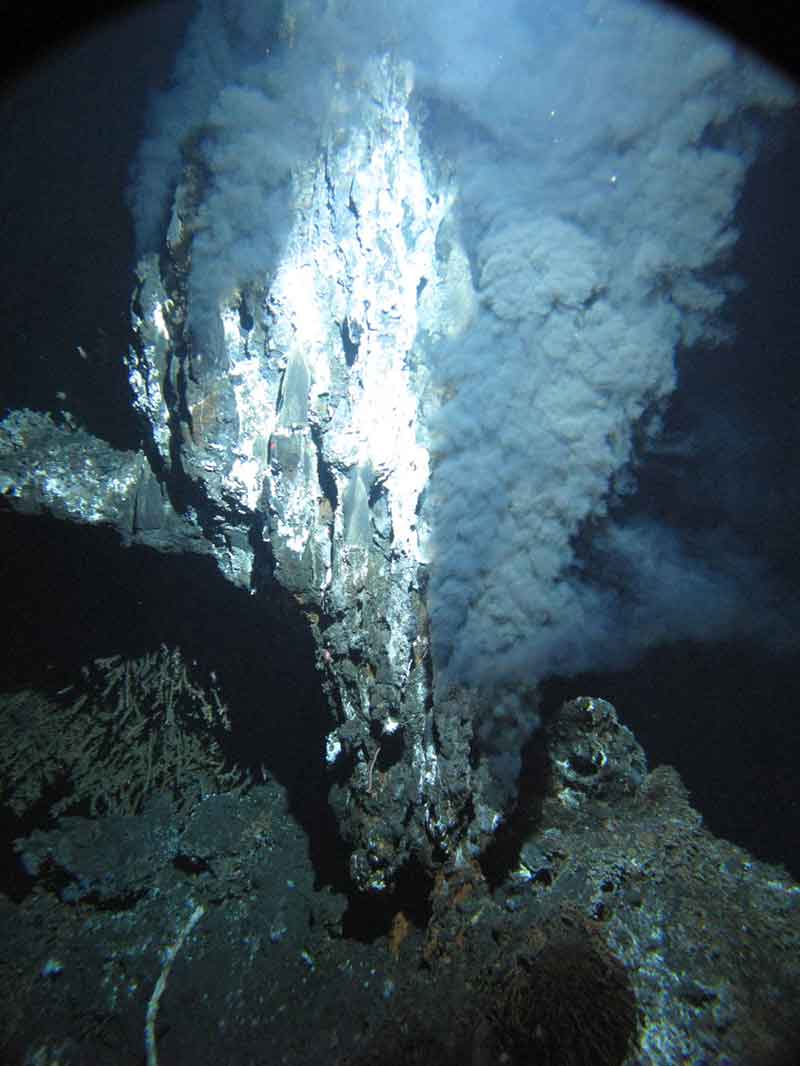

A black smoker chimney named ‘Boardwalk’ emitting 340°C (644°F) hydrothermal fluids in the northeastern Pacific Ocean at a depth of 2,200 meters (7,260 feet). Microbes grow within and on the surface of such mineral formations. Image courtesy of James F. Holden, UMass Amherst. Download larger version (jpg, 663 KB).

When I was 11 years old, the biology taught in my school was shaken to its core by a strange new discovery on the bottom of the ocean: thousands of animals huddled around super hot fluids shooting from the seafloor. These sites were called ‘deep-sea hydrothermal vents’. What made this discovery so amazing was that these animals thrived far from any sunlight. You see, up to that point, we had been taught that all life ultimately relies on photosynthesis to form the base of the food web. So how could these animals be living so well without the sun? The answer was rather stunning.

It turned out that those hot fluids coming out of the seafloor were heated by volcanoes and were rich in metals and gases that were providing microorganisms such as bacteria with the energy and nutrients that they need to grow. Instead of photosynthesis, these microbes were growing by a process called ‘chemosynthesis’ and were providing the animal with the food that they needed to grow. Some of these animals didn’t even have a mouth or a stomach! Instead, they had a sack inside of them called a ‘trophosome’ full of microbes that feed off of the volcanic gases and provide food and energy for the animal in a process called ‘symbiosis.’ Suddenly our understanding of life was completely changed, not to mention our school books!

In college, I began studying these unusual hydrothermal vent microbes. I focused my attention on one group of microorganisms called ‘hyperthermophiles,’ which means “super-heat lovers”. These are the hottest known forms of life on the planet and can grow at temperatures up to 122°C (252°F), even higher than the temperature of boiling water! They live inside the rocks surrounding hydrothermal vents and are heated and nourished by the volcanic fluids. They also have strange ways of living. You see, the energy and carbon we humans need comes from eating things like meat and vegetables and passing electrons from these foods to the oxygen in the air that we breathe.

Helene Ver Eecke, a graduate student from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, dissects a black smoker chimney sample collected from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent to isolate new hyperthermophilic microbes. Image courtesy of James F. Holden, UMass Amherst. Download larger version (jpg, 549 KB).

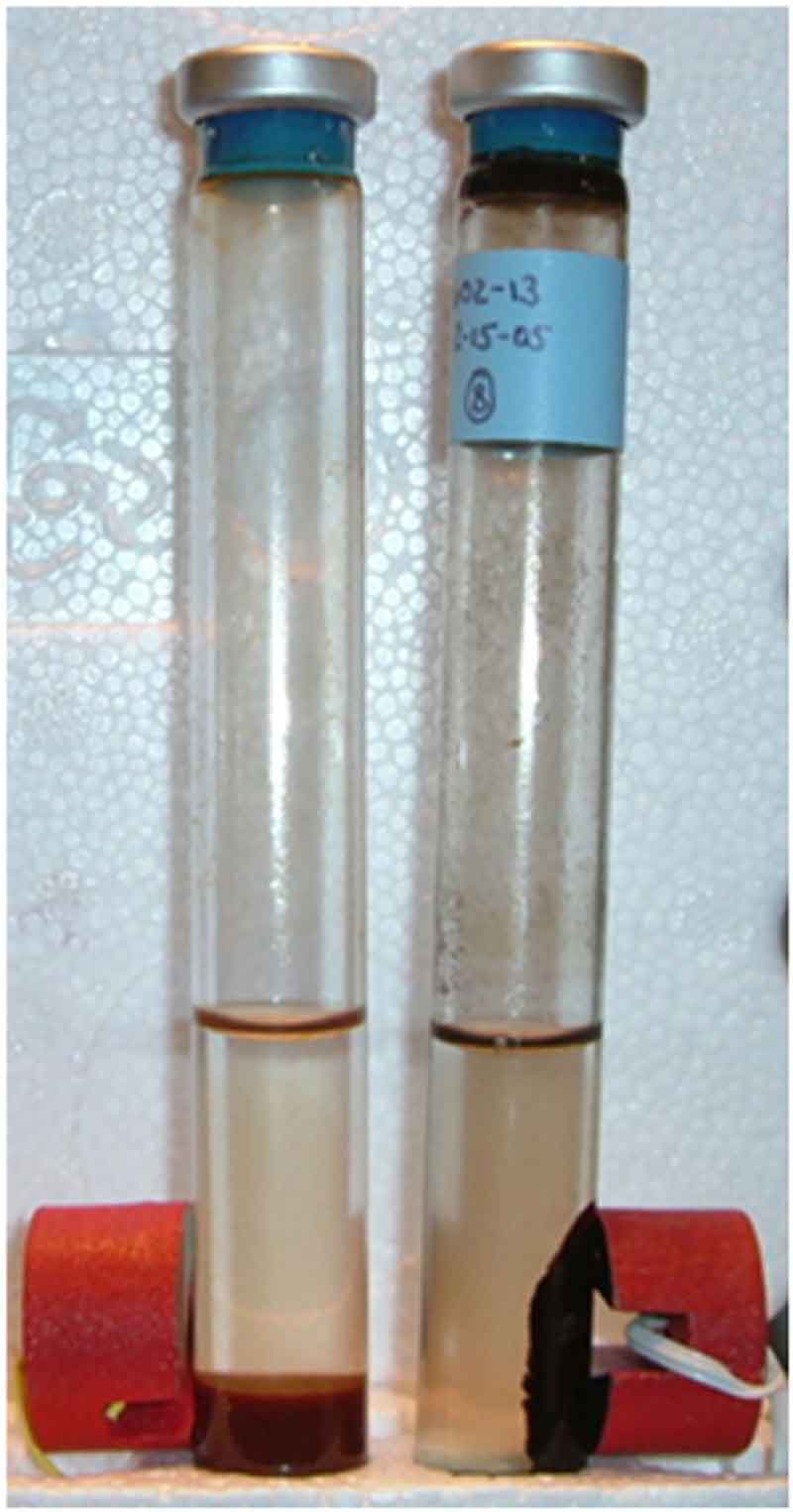

Deep-sea hyperthermophiles can get their energy and carbon from the hydrogen and carbon dioxide gases that are in the volcanic fluids. They create energy by taking the electrons in hydrogen and passing them to things like sulfur and carbon dioxide. Some of them can even make energy by passing the electrons from hydrogen to iron rust similar to what you see on cars to make black magnetic iron – they can actually feed on rocks! Others make methane gas that is flammable and can be used by humans to generate electricity.

So beyond microbes that feed on rocks and live inside of animals without mouths, what have we learned about these strange microbes that makes a difference in our lives? First, it turns out that the proteins in these organisms are useful for many things. When people like scientists and police detectives want to make billions of copies of DNA in a test tube, they use a protein called ‘DNA polymerase’ that comes from these deep-sea hyperthermophiles to make the copies. Other proteins from these microbes called ‘hydrolases’, which break large chains of organic molecules into smaller subunits, can be used to make food additives like sweeteners, soften cotton fabrics, remove spots from our clothes when we do our laundry in hot water, and help extract oil and gas from the ground. We’re even looking at ways that we can use these organisms to remove some of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and turn it into fuels for our cars and to generate electricity in ways that are not harmful to the environment.

Second, we think that some of the microbes from hydrothermal vents are a lot like life on Earth billions of years ago. By studying life at deep-sea vents, we may get an idea of how life existed when the Earth was much younger and different than it is now. Furthermore, if life can exist without sunlight in places where water and volcanic rock come into contact with each other, then maybe this could support life beyond Earth. Hydrothermal vent microbes also give us an idea of what to look for as we search for life on Mars and some of the moons in our solar system. One example is the moon Europa that circles Jupiter, which we think has a deep, dark ocean under its icy shell and active volcanoes at the bottom. Perhaps there are hydrothermal vents there and elsewhere.

Growth of hyperthermophilic microbes that grow at 95°C (203°F) and convert hydrogen gas, carbon dioxide gas, and iron rust (brown material in left tube) into black magnetic iron (right tube). Red magnets are seen flanking both tubes. Image courtesy of James F. Holden, UMass Amherst. Download larger version (jpg, 284 KB).

Finally, the biology of these strange microbes holds all kinds of secrets that are useful for improving medicine, the environment, and our daily lives. None of us were born too late to make these fantastic discoveries. They are there waiting to be found!

It turns out that hydrothermal vents around the world are very different from each other and support different kinds of microbes. We’re excited about exploring the waters of Indonesia for hydrothermal vents because this is one of the most volcanically active areas in the world. We think that there is a good chance that several different types of hydrothermal vents with different kinds of chemistry and microbes might exist really close to one another. This also gives us a chance to introduce these remarkable environments to the people of Indonesia and the rest of the world.

We'll be using special unmanned submarines to search the seafloor for places where we think these microbes are growing. Often times we see them coating the rocks around vents like a thick blanket. Our expedition this summer will move us one step closer to understanding these special environments and the unusual microbes that live in them.