New Deep-Sea Research Sheds Light on Century-Old Mystery

Scientists Nicholas Bezio and Allen G. Collins have published new evidence to help solve a deep-sea mystery that began over a hundred years ago. Their research, which relies on cutting-edge scientific tools and samples from NOAA Ocean Exploration-led expeditions on NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer, expands our understanding of a fascinating animal and serves as a valuable reminder that good science often takes both teamwork and time.

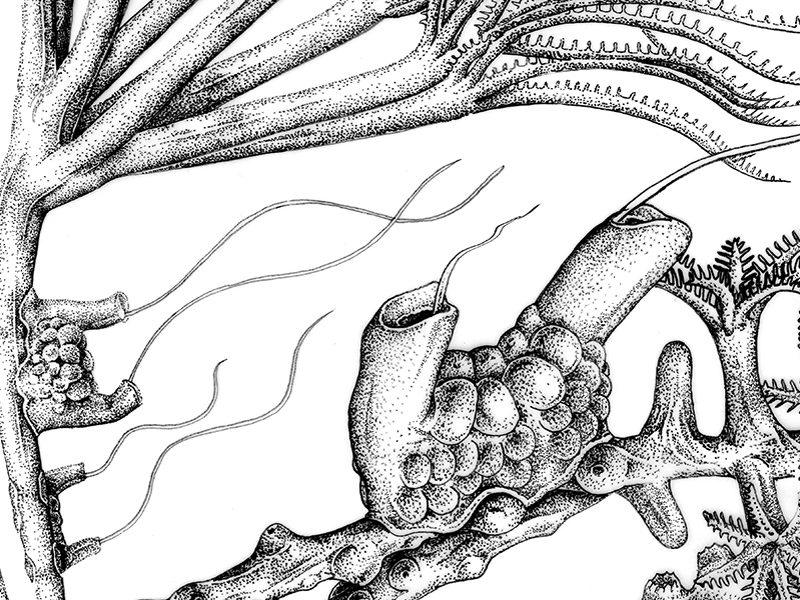

Art of the deep-sea comb jelly discovered in 1910, Tjalfiella tristoma. Image courtesy of Nicholas Bezio. Download largest version (4.47 MB).

In 1910, Dr. Theodore Mortensen and his team discovered a new species of ctenophore (a type of marine invertebrate commonly known as a “comb jelly”) off the coast of Greenland. Rather than swimming through the water, this comb jelly spent most of its life attached to a seafloor animal called a sea pen. That isn’t particularly uncommon: about a quarter of comb jelly species are benthic, meaning they live on the ocean floor. The remarkable part of Mortensen’s discovery was that, while the vast majority of similar ctenophores live in shallow water, this one was found in the deep sea.

Another expedition in 1928 found more examples of the deep-dwelling comb jelly, which had been given the scientific name Tjalfiella tristoma, only a few miles away from the original discovery. Just like on the 1910 expedition, samples were collected, described, and preserved in a museum collection. But then, suddenly, progress stalled.

For the next 90 years, no further examples of this remarkable species were found. The preserved samples sat on the shelf as time took its toll. While the animals collected in 1928 remained in good condition, Mortensen’s 1910 originals decayed to such an extent that they became unusable for research. T. tristoma remained a mystery known only from two discoveries in the deep waters of Greenland. The trail had gone cold.

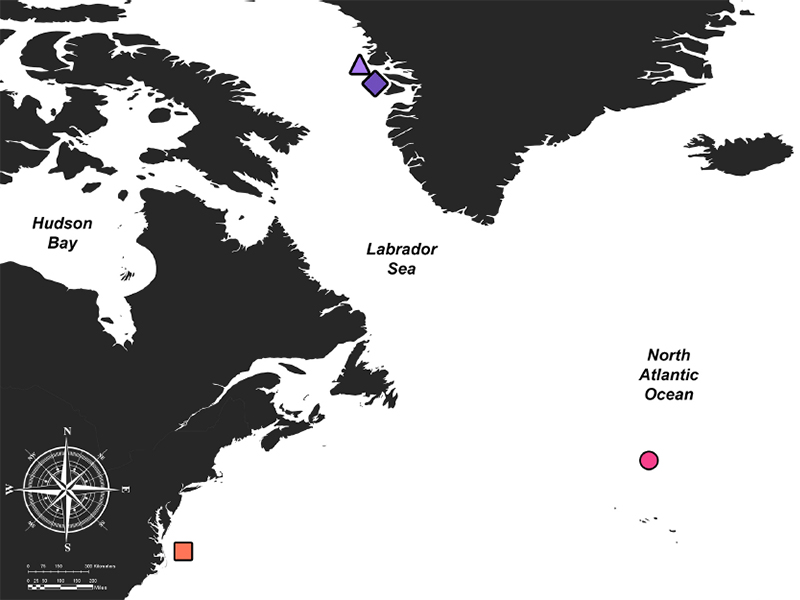

Finally, in 2018, a breakthrough arrived from an entirely unexpected place. A NOAA Ocean Exploration-led team aboard NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer found deep-sea comb jellies that looked extremely similar to T. tristoma not near Greenland, but off the coast of North Carolina. Just four years later, a separate NOAA Ocean Exploration-led team identified another group of similar animals about 300 kilometers (186 miles) north of the Azores in the Atlantic Ocean. After a wait that spanned generations, two new clues to the mystery had been found in startlingly different areas.

The new examples of species that looked remarkably similar to T. tristoma were found very far from the original two discoveries. Diamond—Type locality specimen by Mortensen (1910, 1912), Triangle—Sample (NhMD88841) collected by Kramp in 1928, Square—Sample collected by NOAA (UNSM-Iz-1490693) in 2018, Circle—Sample collected by NOAA (USNM-Iz-1674065) in 2022. Image courtesy of Bezio et al. 2024 . Download largest version (120 KB).

Realizing how remarkable these finds were, scientists Nicholas Bezio and Allen G. Collins leapt at the chance to investigate how these new discoveries were linked to T. tristoma and other comb jellies.

“There are only two known species of platyctenes (benthic comb jellies) that live in the deep sea, one of which is T. tristoma, but deep-sea footage and samples from NOAA Ocean Exploration expeditions suggest that there could be many more that are still undescribed,” said Bezio, who is studying the animals for his Ph.D. “To start learning about those possible new species and how they fit into deep-sea ecosystems, we need to understand more about the species that are already known to science. We have almost no information on T. tristoma, which is why finding these new comb jellies that looked extremely similar to it was so exciting.”

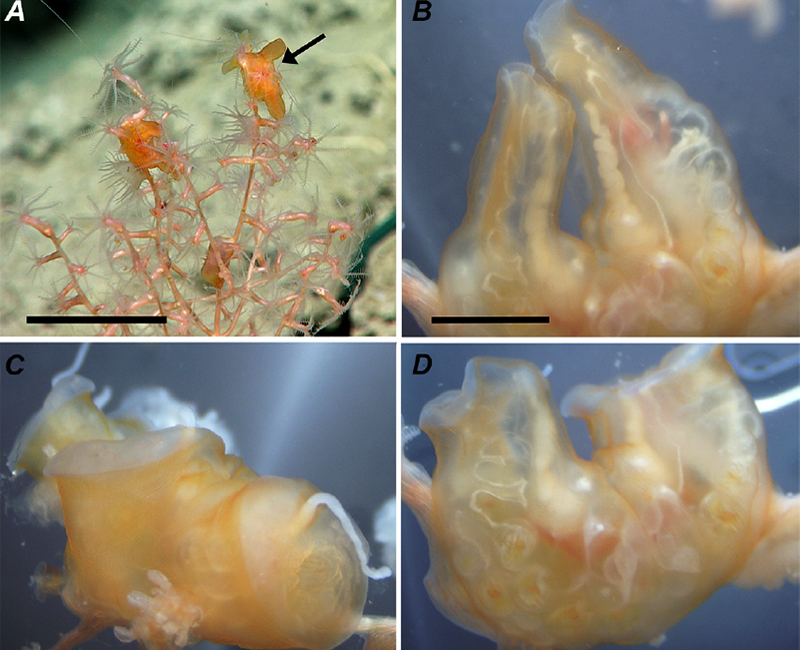

Living specimens of benthic comb jelly Tjalfiella aff. tristoma, found on a NOAA Ocean Exploration expedition in 2018. This was the first time an animal that appeared nearly identical to Tjalfiella tristoma had been sampled since 1928. Image courtesy of Bezio et al. 2024 . Download largest version (910 KB).

Collins, who works for the National Systematics Laboratory of NOAA Fisheries and who is an affiliated research scientist and curator at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, knew that comparing the fresh samples to the preserved ones from 1928 could provide a breakthrough.

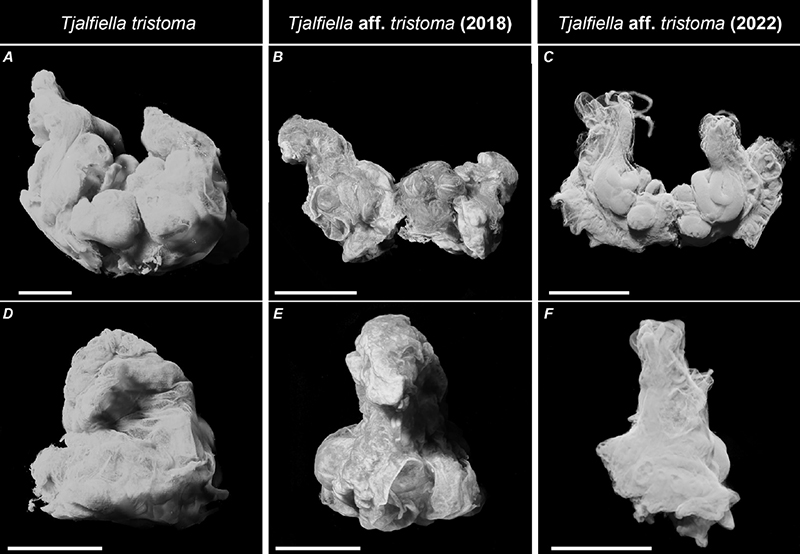

“Fortunately, unlike most ctenophores, platyctenes preserve fairly well,” Collins said. “This fact allowed us to use novel techniques on both the recently collected specimens at the Smithsonian and T. tristoma samples from the Natural History Museum of Denmark that were nearly a century old.” The team compared the samples with a technique called MicroCT – essentially a 3D X-ray or a tiny version of a CAT scan – to study the insides of the fragile specimens without damaging them. This was the first time that MicroCT had ever been used on comb jellies. Bezio and Collins also studied the specimens recently collected by NOAA Ocean Exploration using genome skimming, a technique used to create genetic “barcodes” that are useful for identifying species. The combination of these tools led Bezio and Collins to some unexpected conclusions.

“What took us by surprise was that, while genetically very similar, these samples represent two different species – and maybe even three,” said Bezio. “That suggests that the diversity of deep-sea platyctenes is likely higher than we originally thought.”

MicroCT 3D reconstructions of the samples from 1928, 2018, and 2022. A. Tentacular view of T. tristoma, B. Tentacular view of T. aff. tristoma (2018), C. Tentacular view of T. aff. tristoma (2022), D. Stomodeal view of T. tristoma, E. Stomodeal view of T. aff. tristoma (2018), F. Stomodeal view of T. aff. tristoma (2022). Image courtesy of Bezio et al. 2024 . Download largest version (442 KB).

Because the specimens collected in 1928 were not preserved in a way that would have allowed for genetic work that was unknown at the time, it remains unclear whether either of the new discoveries is T. tristoma itself or if both are just close relatives. Still, the findings show that this unique genus of deep-sea comb jelly likely plays a role in far more deep-ocean ecosystems than was known before. Collins noted that this new lead and the genetic data from the study will be a big help to future science.

“The genetic data collected during this research will allow these species to be detected with techniques that NOAA is using as part of its ‘omics strategy, such as sequencing environmental DNA found in the ocean,” said Collins. “The more information we have, the easier it becomes to find these fascinating animals and understand their place in deep-sea environments.”

With national and international reliance on the ocean constantly growing, the need to understand the deep sea is more pressing than ever. As we continue to study and learn, the greatest lesson from Bezio and Collins’ work may be that scientific progress takes teamwork and a commitment to building on the efforts of those who came before. This research would have been impossible without samples painstakingly cared for by the Smithsonian, modern research conducted by NOAA Ocean Exploration teams, and records created a century ago by experts at the Natural History Museum of Denmark trusting that their work would lead to future discoveries. It’s up to the scientists of today and tomorrow to carry on that important legacy.

Bezio, N., and Collins, A.G. (2024) Redescription of the Deep-sea Benthic Ctenophore Genus Tjalfiella from the North Atlantic (Class Tentaculata, order Platyctenida, family Tjalfiellidae). Zootaxa, 5486(2), 241–266. Access the full article online

Related Links

Published August 16, 2024