Newly Discovered Aleutian Margin Cold Seeps Host Gas Hydrate and Dense Colonies of Tubeworms

By Carolyn D. Ruppel, U.S. Geological Survey, Woods Hole, Massachusetts

Shannon Hoy, NOAA Ocean Exploration

Sam Cuellar, NOAA Ocean Exploration

Dive 04 of the Seascape Alaska 3: Aleutians Remotely Operated Vehicle Exploration and Mapping expedition took place on July 18, 2023. During the dive, we explored Aleutian arc cold seeps (Sanak seeps) that were discovered only two months earlier during the Seascape 1: Aleutians Deepwater Mapping expedition. The dive at 2,100 meters (6,900 feet) water depth was carried out using NOAA Ocean Exploration’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Deep Discoverer (D2), designed and operated by the Global Foundation for Ocean Exploration . Exploration of the Sanak seeps resulted in the discovery of bubble plumes, gas hydrates, thousands of tubeworms, patches of chemosynthetic clams, and special rocks produced by microbial processes.

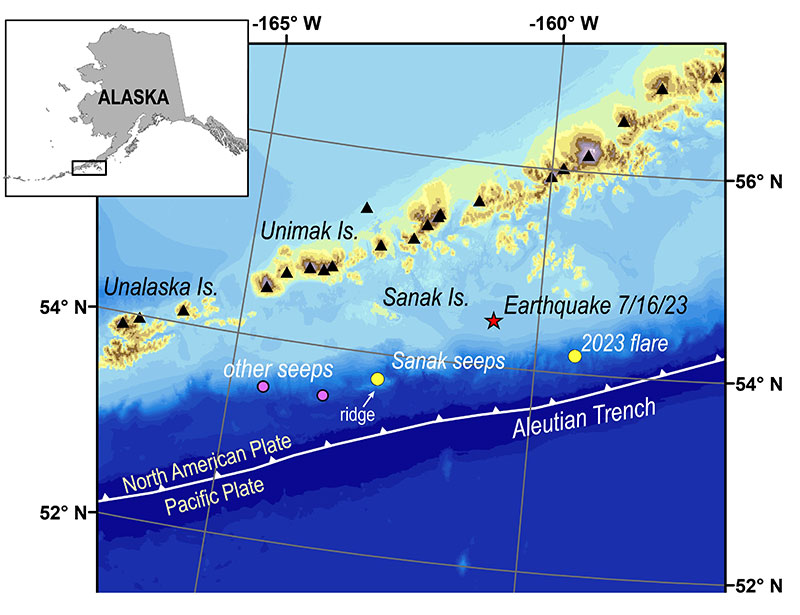

Inset and regional map showing location of the Aleutian trench and island arc; new seeps found by NOAA Ocean Exploration in May 2023 (yellow circles), including the Sanak seeps investigated in Dive 04; previously investigated seeps (purple circles); the magnitude 7.2 earthquake that occurred on July 16, 2023 (red star); and volcanoes (black triangles). Image courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey. Download larger version (jpg, 3.1 MB).

Rendering of the water column gas plume (white dots) that guided the Seascape Alaska 3 dive at the Sanak seeps, showing the bottom part of gas flares that can be imaged to 1,500 meters (4,920 feet) above the seafloor. Bathymetry is contoured at 10 meters (33 feet), and colors show slope in degrees, with red being steep angles. This view looks east along the line of seeps, and the total width of the seeping area is about 600 meters (1,950 feet). The Aleutian trench is towards the right. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Seascape Alaska. Download largest version (4.0 MB).

From May to September 2023, NOAA Ocean Exploration is conducting six Seascape Alaska expeditions to collect bathymetry data and explore the seafloor in the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Arc. During routine mapping operations in May 2023, expedition staff, including the NOAA coauthors of this feature story, NOAA mappers Amanda Bittinger and Treyson Gillespie, and Senior Survey Technician Colin Schmidt, imaged gas bubbles rising more than 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) above the seafloor in several areas offshore the remote Aleutian Islands. Such gas flares can be visualized because the sound waves used to generate high-resolution seafloor maps are disrupted when they pass through gas bubbles.

A review of the new gas flare identifications from the Seascape Alaska 1 dataset led scientists to choose a site approximately 48 km (30 miles) offshore Sanak Island as the highest-priority target for the first D2 exploration of a suspected gas seep in this area. Before the ROV dive, overnight mapping surveys, performed by NOAA mappers Anna Coulson and Marcel Peliks, not only confirmed the presence of the gas flares imaged in May, but also mapped a larger area of gas emissions with more discrete seeps than originally detected in May.

The Sanak seeps trace a 600-meter (1,950-foot) line on a landward-facing terrace of a seafloor ridge that runs parallel to both the Aleutian trench to the south and the Aleutian Islands to the north. The trench marks where the Pacific plate is diving beneath the North American plate. The Aleutian Islands, which are comprised of dozens of active volcanoes, have developed near the edge of the North American plate. Like similar tectonic plate boundaries around the Pacific “Ring of Fire,” the Aleutian Arc is characterized by frequent large earthquakes and folding, faulting, and other seafloor deformation.

The seafloor ridge that hosts the Sanak seeps appears to be formed by a number of fault blocks oriented parallel to the ridge. The linear arrangement of the Sanak seeps implies that they may occupy a fault trace tapping deep migrating fluids. The line of seeps emits a curtain of gas rising more than 1,500 meters (4,920 feet) above the seafloor.

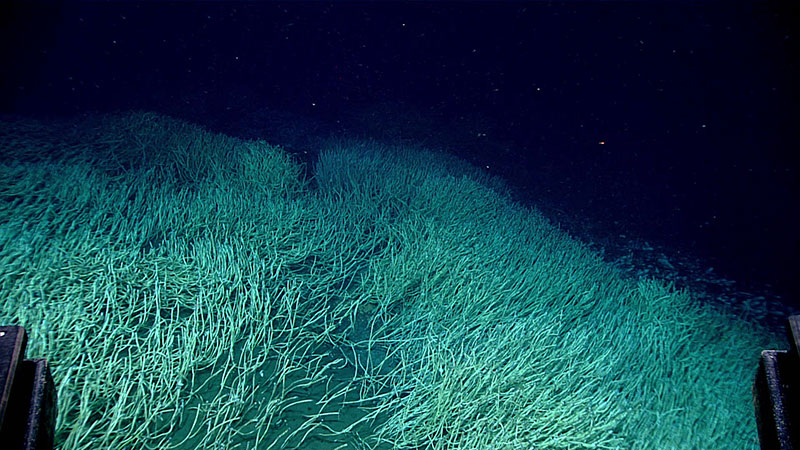

Dive 04 started on the western end of the Sanak seeps, and the ROV almost immediately encountered large, dense colonies of siboglinid tubeworms, which are chemosynthetic tubeworms found in both cold seep settings and at warm hydrothermal vents along the global mid-ocean ridge system. The tubeworms, which rely on sulfide (a byproduct of the microbial processing of methane) to sustain life, have previously been found at the two other cold seeps explored just to the west, but 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) deeper.

Clusters of densely packed siboglinid tubeworms in a field of view several meters wide and stretching several meters into the distance were found during Dive 04 of the Seascape Alaska 3 expedition. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Seascape Alaska. Download larger version (jpg, 1.5 MB).

Close-up of the tubeworms imaged during Dive 04 of the Seascape Alaska 3 expedition, showing the red hemoglobin-filled tentacles that bind with oxygen and sulfide. The part of the tubeworms that is visible above the seafloor is estimated to be 70 to 100 centimeters (2 to 3 feet) long, and the tips containing the tentacles are up to 1.5 centimeters (0.6 inches) across. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Seascape Alaska. Download largest version (1.7 MB).

The Sanak seep tubeworm colonies consist of hundreds of individuals with an estimated 70 to 100 centimeters (2 to 3 feet) of the tube extending out of the sediment. Below the seafloor, the worms’ tubes can stretch for meters to reach sulfide. The tubeworms were found in profusion along most of the 200-meter (~650-foot) section of the seep field that D2 had time to explore during the dive. Previous studies in the Gulf of Mexico found that siboglinid tubeworms may live up to 200 years.

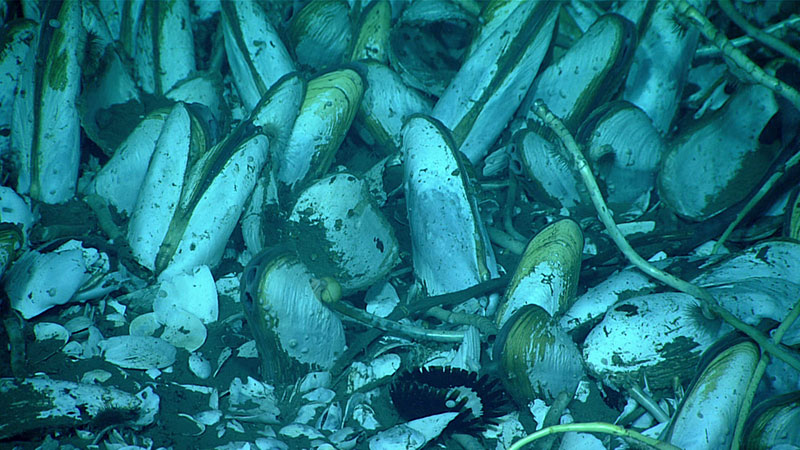

Among the tubeworm colonies were both small and large bivalves partially buried in the seafloor sediments. These have previously been identified as Calyptogena clams at seafloor seeps to the west. These clams typically use sulfide, not methane, to power metabolic processes, and their association with the sulfide-dependent tubeworms is not surprising.

Chemosynthetic clams embed in seafloor sediment to extract sulfide, observed during Dive 04 of the Seascape Alaska 3 expedition. These clams have an estimated 10-15 centimeters (4-6 inches) exposed above the seafloor. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Seascape Alaska. Download larger version (jpg, 1.3 MB).

Gas hydrate (white, icelike material) seen during Dive 04 of the Seascape Alaska 3 expedition under a ledge of carbonate rock, with clams, tubeworms, anemones, and a crab. The total width of the hydrate is estimated to be more than a meter. Seeping gas bubbles beneath the hydrate mass form a coating of hydrate, and then the hydrate-armored bubbles accumulate against the underside of the carbonate as they rise. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Seascape Alaska. Download largest version (1.9 MB).

Along the dive track, D2 frequently encountered slabs of a special type of carbonate rock that precipitates when microbial processes consume methane. Methane-derived authigenic carbonates form below the seafloor and probably need thousands of years to accumulate. Their ubiquitous presence at the Sanak seeps may indicate that gas emissions were occurring thousands of years ago, although further information would be required to determine whether the seeps have been continuously active over millennia.

For most of the dive, no bubbles were observed leaking from the seafloor even though D2 was traversing an area where gas flares had been detected at high resolution in the surveys conducted just before the dive. As the dive progressed, D2 did encounter gas continuously seeping as discrete bubbles from bare patches of seafloor adjacent to tubeworm colonies. In one instance, the gas leakage was episodic, as if the system recharged for some period before the gas was suddenly released.

Gas hydrate, an icelike substance formed when methane combines with water at these profound pressures and low temperatures, was observed forming solid masses under several carbonate overhangs near gas seeps. A highlight of the dive was spectacular footage of individual flattened gas bubbles being emitted at the seafloor, immediately forming a coating of the hydrate ice, and then wobbling in the water column as they ascended. In one location, hydrate-encased bubbles even accumulated on tubeworms that were oriented across a bubble stream.

Tubeworms within a gas seep feed, seen during Dive 04 of the Seascape Alaska 3 expedition. The gas bubbles in the water column in the center of the photo appear as flattened flakes surrounded by gas hydrate and are less than 0.75 centimeters across. Video courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Seascape Alaska. Download largest version (mp4, 12.6 MB)

Published July 24, 2023

Relevant Expedition: Seascape Alaska 3: Aleutians Remotely Operated Vehicle Exploration and Mapping