Extensive Coral Communities found in Glacier Bay National Park

April 18, 2016

This video features highlights from the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition. Video courtesy of the Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park expedition and UCONN-NURTEC. Download larger version (mp4, 49.6 MB)

On a recent research expedition in Alaska, scientists aboard the R/V Norseman II conducted the first-ever deepwater exploration of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve. Using both surveys by scuba divers and the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Kraken2, scientists found an abundance of cold-water corals and associated organisms that use these corals as habitat, from the very bottom to the top of the submerged portion of the fjords. Prior to the expedition, little was known about ecosystems in the depths of the fjord and records of corals were sparse. Led by Dr. Rhian Waller of the University of Maine, this project was funded as part of NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research’s 2014 Federal Funding Opportunity.

“This expedition was incredibly exciting. Not only did we find abundant cold-water coral communities at both deep and shallow depths, we recorded species new to this area and abundant life living around these corals, and we documented and took imagery for the first time of cold-water coral ecosystems existing within one of our national parks,” said Dr. Waller when asked about the success of the expedition.

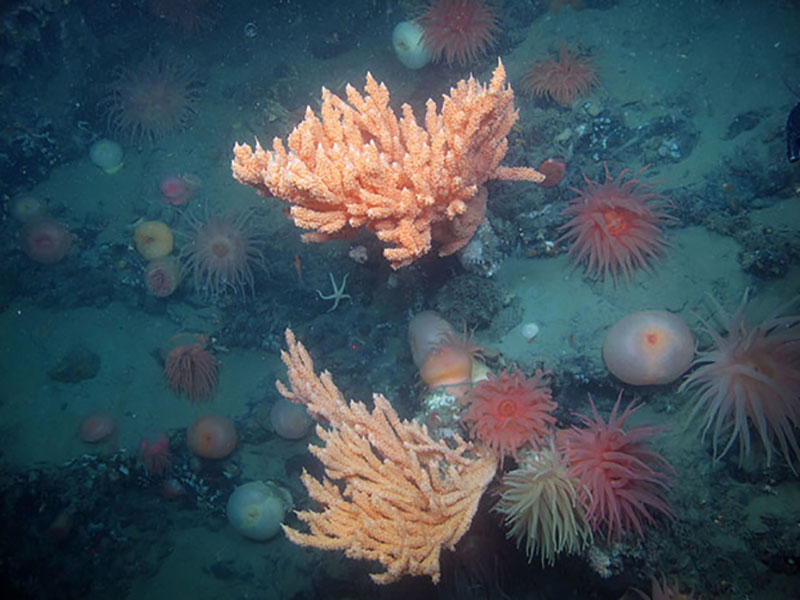

Throughout the expedition, scientists were struck by the size of the corals, some estimated to be up to three meters tall, and the amount of corals observed on nearly every ROV dive and the majority of scuba surveys. Stony corals were also observed for the first time within the park, and a species of stoloniferous octocoral – a type of encrusting coral – was found at greater depths than has been observed anywhere else in the world.

A diversity of fish, including several different species of rockfish, cod, and sculpin, and a variety of marine invertebrates, including sea urchins, nudibranchs, polychaetes, shrimp, as well as several types of crabs and sea stars, were documented during the expedition. A number of these species are likely new observations within Glacier Bay.

Bob Stone, fisheries biologist from NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center, said, "One thing that surprised me the most was the abundance of plankton – food for these corals – in and around the deepwater coral groves. We got a rare and very important glimpse of ecological succession in action, virtually watching the corals claim territory as the glaciers retreat back into the bay. It was quite spectacular."

Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in southeastern Alaska is located in one of the great fjord regions of the world. It features a number of glacially carved, narrow channels with high cliffs and deep basins. Many fjord systems support benthic – or bottom-dwelling – communities that are usually found only in much deeper, offshore waters. The park protects a unique and dynamic ecosystem and also serves as a natural laboratory for scientific discovery. The first indication of deepwater corals in the park occurred in 2004 when Stone observed colonies of Red Tree Corals, Primnoa pacifica, at scuba diving depths. The same year, a team of scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey documented a few sporadic occurrences of colonies at deeper depths via a towed underwater camera survey.

"Deepwater marine environments are one of the least studied areas of the park. By providing basic scientific information on the distribution and diversity of seafloor habitats and communities, this research will help park managers better protect these unique ecosystems," said Lisa Etherington, Chief of Resource Management, Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve.

In the coming months, the project’s scientists will analyze video data and collected biological samples to better understand the population genetics, spatial distribution, reproductive ecology, and food web associated with these corals. Conductivity, temperature, and depth (CTD) data and water samples collected during the expedition will be analyzed to help define the unique oceanographic conditions that allow these communities to exist in the fjords of the park.

The data collected on this expedition will help NOAA better characterize unknown areas of our oceans and understand essential fish habitats as well as deep-sea coral life history and population structure. Aside from NOAA, partners of the project include the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Park Service, the University of Maine, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and the University of Connecticut.

Additional information about the expedition, including additional imagery, background, and stories about the mission, can be found at http://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/16glacierbay/welcome.html.

A large colony of Red Tree Coral is brought onboard the R/V Norseman II by Jim Wells (left) and Eric Glidden. This colony was collected to better understand how these corals are interacting with their environment and how the populations have developed in the bay. Image courtesy of Dann Blackwood, Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park. Download image (94 KB).

The R/V Norseman II, seen here in Muir Inlet in Glacier Bay National Park, served as the platform for both ROV and scuba diving operations during the expedition. Image courtesy of Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park. Download image (82 KB).

The team deploys ROV Kraken2 within Johns Hopkins Inlet to explore deepwater communities. Image courtesy of Dann Blackwood, Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park. Download image (106 KB).

Several deepwater areas explored had high densities of Red Tree Corals. Image courtesy of Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park and UCONN-NURTEC. Download image (126 KB).

Bob Stone, NOAA, measures a colony of Red Tree Coral during a scuba survey in Glacier Bay National Park. Image courtesy of Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park. Download image (55 KB).

A sculpin rests on a large Red Tree Coral. During this expedition, a number of fish were found collocated with large coral colonies. Image courtesy of Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park and UCONN-NURTEC. Download image (126 KB).

At times, it was difficult to see the Red Tree Corals beyond the large schools of fish that were documented at several sites. Image courtesy of Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park and UCONN-NURTEC. Download image (114 KB).

Even in the areas with young Red Tree Coral colonies, there was an abundance of life. Image courtesy of Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park and UCONN-NURTEC. Download image (94 KB).

Aside from corals, scientists on this expedition documented a diversity of invertebrates including an abundance of sea stars, bivalves, echinoderms, mollusks, and crustaceans, like this juvenile king crab. Image courtesy of Dann Blackwood, Deepwater Exploration of Glacier Bay National Park. Download image (66 KB).