Collapsed Volcano Inspires Natural Coral Reef Lab

July 16, 2014

As climate change continues, scientists are in a race to predict the ways it will affect the natural environment. By understanding climate change, they hope to anticipate issues related to food supply, habitat management, and natural resources.

One area of concern is ocean acidification. The ocean absorbs about 25 percent of all of the carbon dioxide (CO2) released into the atmosphere as a result of our consumption of fossil fuels. The result is that the delicate chemistry of the ocean is being altered—the pH is steadily being lowered, making seawater more acidic.

But how would a scientist interested in understanding what may occur as the oceans become more acidic go about studying this issue?

In the early 2000s, geochemist David Butterfield came up with an idea: using Maug.

Meet Maug

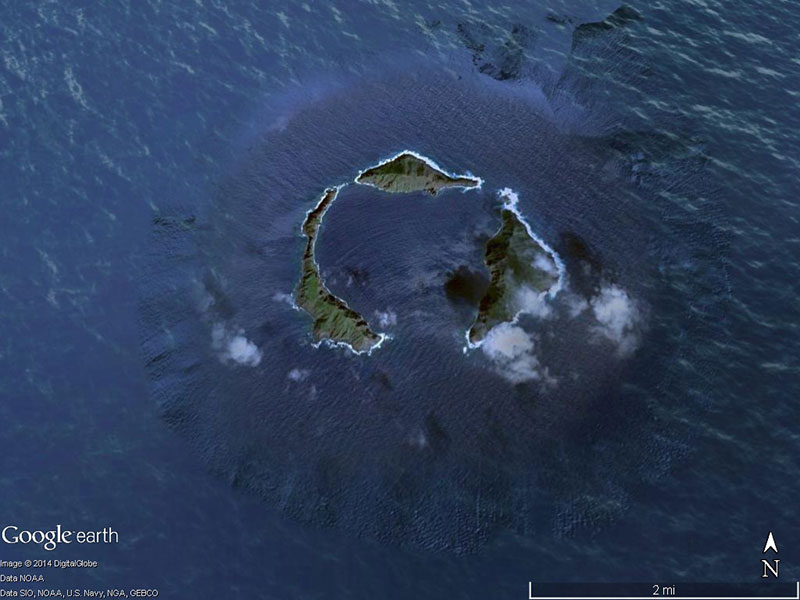

Despite sounding like one of the more obscure monsters in the Godzilla franchise, Maug is a volcano in the Northern Mariana Islands, in the western Pacific Ocean, that collapsed after a long-ago eruption. The remaining structure has been flooded with seawater, leaving three islands that form a circle around a caldera, or crater.

The volcano itself emits gas and heat from the magma beneath it, and shallow gas vents along the inner shoreline emit CO2—right next to a coral reef.

Meet David Butterfield

Butterfield works for the Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean at the University of Washington. The Institute is funded in part by NOAA, and Butterfield is housed at NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, in Seattle.

His research is part of the Earth Ocean Interactions Program, which studies how the ocean interacts with the underlying solid Earth, focused mainly on submarine volcanoes. About 70 percent of the volcanic activity on Earth happens underwater, much of it in the Ring of Fire, the chain of volcanoes that extends for thousands of miles around most of the Pacific Basin.

Since 2002, the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory has been working with NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research to map and explore the Ring of Fire.

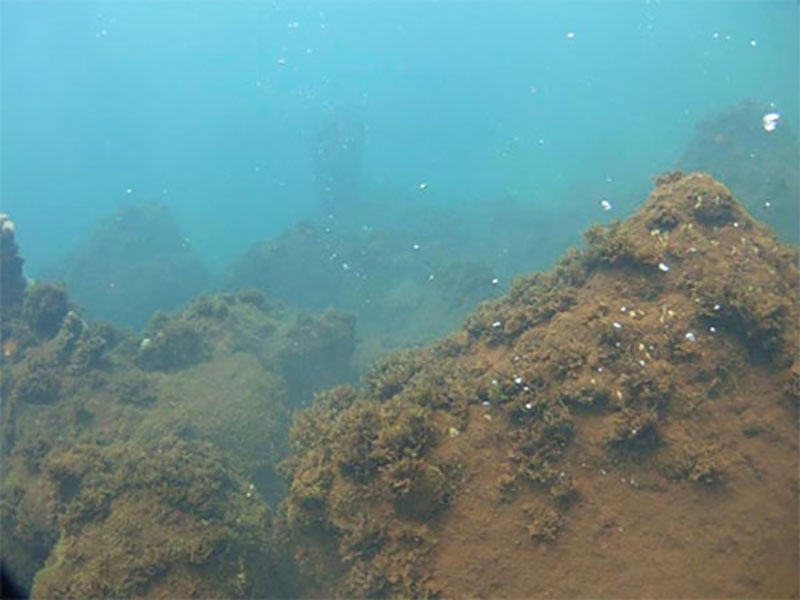

After learning of the shallow gas vents from the oceanographers Rusty Brainard and Chip Young, Butterfield realized that the gas emitted by the vents would change the chemistry of the seawater around the reefs in a process that is similar to the global ocean acidification process. He began thinking about how the effects of the vents on the coral reef could provide clues to how these reefs might respond to the acidifying ocean, and decided to use Maug as a natural laboratory to study the phenomenon.

The Volcanic Ocean Acidification Project

Together with Brainard and Young, who both work at the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, Butterfield and another Earth Oceans Interactions scientist, Joe Resing, requested ship time for a collaborative “Volcanic Ocean Acidification” project.

The NOAA Office of Marine Aviation and Operations—which determines which research projects can be slotted into current NOAA priorities and scheduled expeditions—approved the project in December of 2013. The four scientists would have one week in May 2014 to do their work around Maug, on NOAA Ship Hi’ialakai.

With the ship time awarded, they needed funding for all the other aspects of the trip, including travel costs for participating scientists, supplies, and the shipping of gear needed to support the research. So they approached their old partner, the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, which provided the funding the scientists needed to make the mission happen.

Ultimately, besides Butterfield and Young, about 15 scientists and scientific divers went on the trip to conduct research. Butterfield said that in the two months since the cruise, they have all been busy analyzing the data they collected on the trip, including the data from many water and sediment samples.

When this analysis is done, they anticipate publishing a paper describing the impact of the hydrothermal vents on the coral reef. First results indicate that the surface water pH is locally lowered by 0.1 to 0.2 pH units by the warm vents—the same order of pH decrease expected globally from anthropogenic ocean acidification.

They hope to head another collaborative expedition in 2017, when they’d like to set up long-term monitoring experiments to understand how the ecosystem adapts to low pH and high CO2.