Exploration of Deepwater Habitats off Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands for Biotechnology Potential

All in a Day’s Work

During this expedition, every day was focused on collecting samples and were largely the same tempo. Here, I describe a day’s work on F.G. Walton Smith during Exploration of Deepwater Habitats off Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands for Biotechnology Potential.

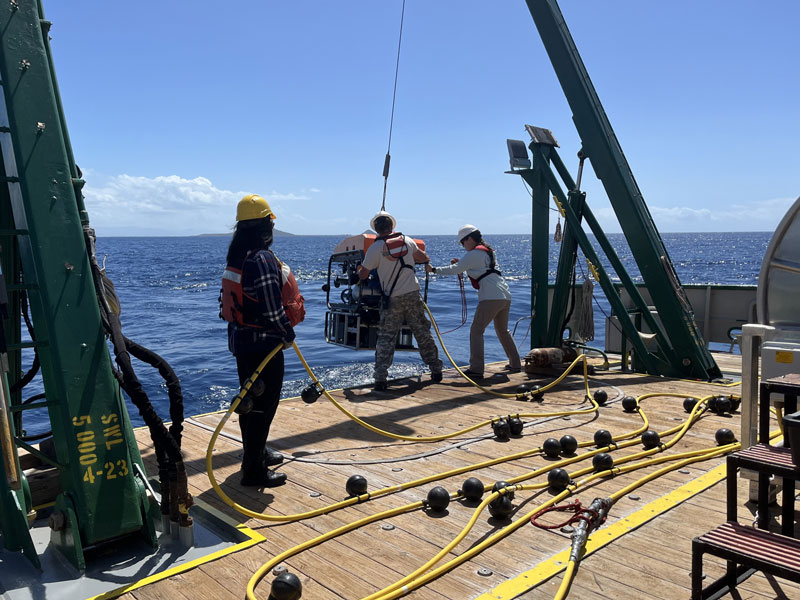

John Reed and Priscilla Winder talked with the captain the morning of a dive, so he knew where we needed to be for an 8 a.m. launch of the remotely operated vehicle (ROV). In preparation for the ROV launch, we started with a hearty breakfast provided by Russell, our great onboard chef, and a pre-dive brief. Once we were all well fed and the ship was where we wanted it to be, the ROV pilots, Jason White and Samantha Flounders, got everything in order and launched the ROV with the assistance of Madison Lytle and Carol Kim.

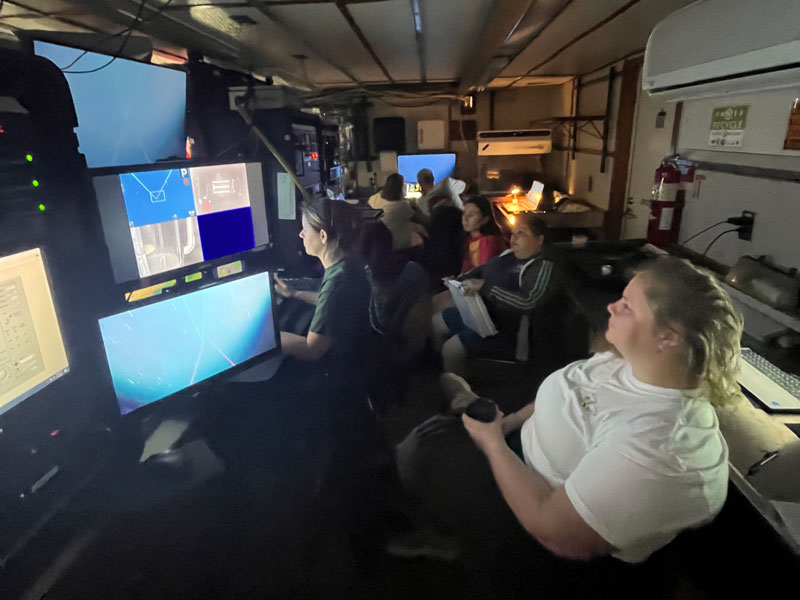

In the control room, we followed the dive on our monitors. John tried to annotate everything that happened during the dive, including the terrain, currents, and observations of fish, corals (including field IDs), and anything else that caught our attention. At another monitor, Megan Conkling, Kirstie Francis, and Carol documented fish, human trash, and corals we did not collect with screenshots and careful notes. Priscilla (and sometimes me) scanned the seafloor for interesting sponges, indicating to the pilot which sponges to collect and how much of the animal to take (leaving a piece of sponge behind allows them to regenerate). Once sample collection began, Courtney Brooks and I got to work annotating each one, recording information such as the field ID, which describes a sample’s possible taxonomy. Field IDs were preliminary; formal identification requires close examination of a sponge’s spicules (structural elements).

A dive usually took about three hours. Once the ROV’s bioboxes were full, the ROV was brought back to the surface. This recovery process took anywhere from a few minutes up to an hour, depending on the depth of the dive. If we wanted to continue collecting from the same site, the bioboxes were exchanged for empty ones, and the ROV was relaunched a few minutes later. If we were moving to a new site, the captain or first mate sped up the ship to get us there, and we did it all again.

Once the samples were aboard the ship, there was a lot to do, starting with printing labels with sample numbers to make sure everything can be properly tracked. Cristina (Cris) Diaz, our onboard sponge taxonomist, and John (our coral taxonomist) organized the samples and placed a tag with a sample number next to each sample. Small pieces of each sponge were saved for DNA studies, microbiology cultures, shipboard chemical analysis, and the sponge biobank. Priscilla, Megan, and Cris documented each sample, taking pictures and making vouchers. Then, the rest of the sample was frozen for future chemical studies.

During all this activity, the scientists took turns eating lunch and documenting the second dive, after which they repeated the sample processing procedures with the new batch of samples.

Even after the ROVs were back on the ship and the samples were processed, the work went on. Kirstie processed the microbiology samples, Megan dissociated the sponge cells for the sponge biobank, Cris started looking at spicules under the microscope, and the rest of the team entered notes into the expedition database so all the information would be available digitally at the end of the expedition.

The days were long and exhausting, yet somehow pleasant. Everyone was so focused on the mission that the ambience was one of exhilaration.

By Esther Guzmán, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, Florida Atlantic University

Published July 24, 2024