Exploration of Deepwater Habitats off Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands for Biotechnology Potential

Culturing the Sponge Microbiome for Natural Product Discovery

The ocean, with its wealth of marine organisms, has proven to be an advantageous place to look for new medicines, with over 20 marine natural product medicines approved globally, to date. A priority of this expedition was to isolate microbes — bacteria and fungi, in particular — from mesophotic sponges (sponges that exist in low light) with the goal of expanding microbial libraries at Mote Marine Lab and Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute (HBOI). Once stored in the libraries, the microbes will be available for scientists to screen for bioactivity (i.e., their effects on living matter) and potential drug discovery.

Marine invertebrates like sponges, tunicates, and mollusks are rich sources of unique natural products, but it’s now recognized that sometimes these products are produced by members of an organism’s microbiome — the microbes that live in it — rather than by the host itself. For example, halichondrin B is a natural product that was originally isolated from a sea sponge, Halichondria okadai, and is used to treat cancer under the brand name Halaven. It’s currently believed that members of this sponge’s microbiome are the true producers of halichondrin B.

Like humans, sponges have rich microbiomes made up of diverse species of bacteria, archaea, and fungi. The members of a sponge’s microbial community can vary depending on the sponge species, geographic location, depth, and a variety of other environmental factors.

Historically, it was estimated that only 1% of microbes found in nature can be grown in a laboratory setting — or "cultured." As our understanding of what it takes for microbes’ to survive increases, the estimate of what can truly be cultured is increasing.

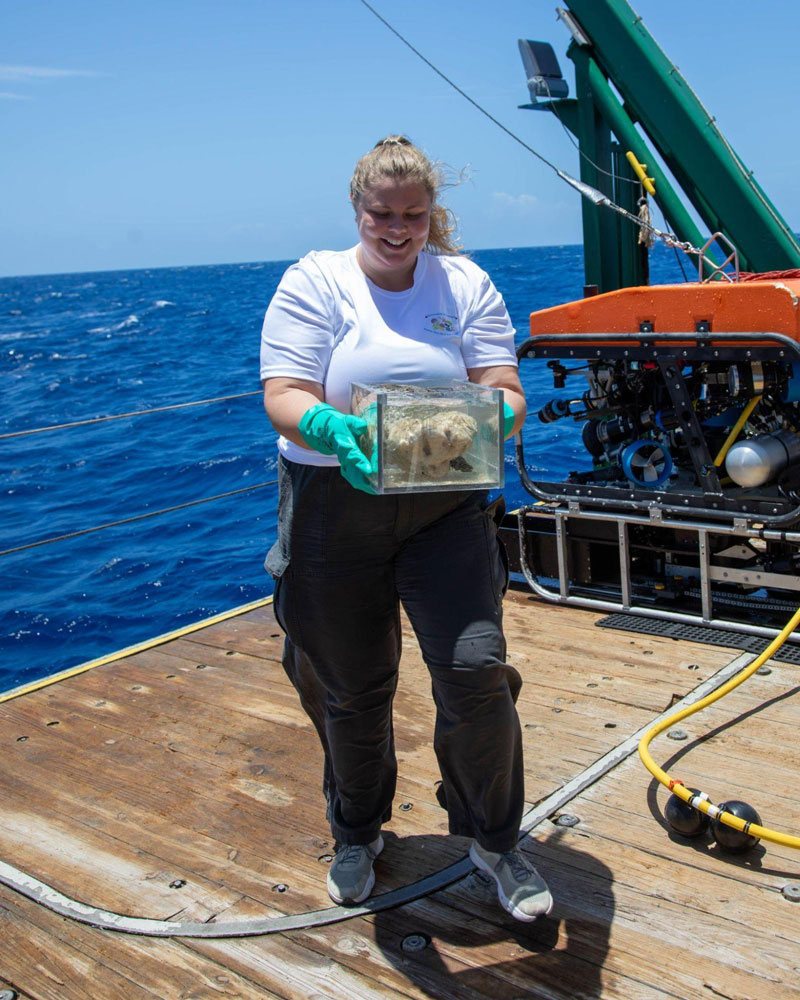

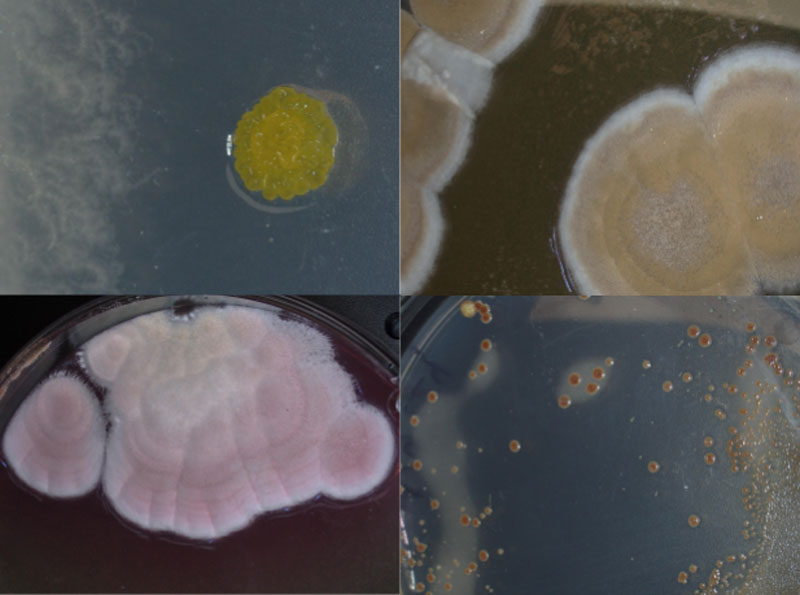

On this expedition, we used six culture media containing different nutrients to try to culture different types of bacteria and fungi. When we collect a sponge at sea, we take a subsample for microbial culture, rinse it in sterile artificial seawater, and ground it into a slurry. We then dilute this sponge slurry and put it onto the chosen culture media in petri dishes, where it can take weeks or months for microbial colonies to grow.

About a month after the expedition, colonies began to appear in the dishes we brought home with us. We then selected colonies for isolation and moved them to new dishes, where we preserved them for later analysis of bioactivity.

HBOI has been building its microbial library since the mid-1980s and now has over 19,000 microbe samples. In my postdoctoral fellowship at Mote, I am working to expand their microbial library. This expedition alone will add hundreds of microbial isolates to my collection. My next step is to test these microbes and their natural products to see if they are bioactive. Might they be antimicrobial or kill cancer cells or harmful algal blooms? Ultimately, my hope is to find new medicines and commercial products that come from the sea.

By Kirstie Tandberg Francis, Mote Marine Laboratory

Published September 24, 2024