Early Encounters on a Western Frontier: The Search for Svyatoy Nikolai (1807-1808)

What Was Russian America?

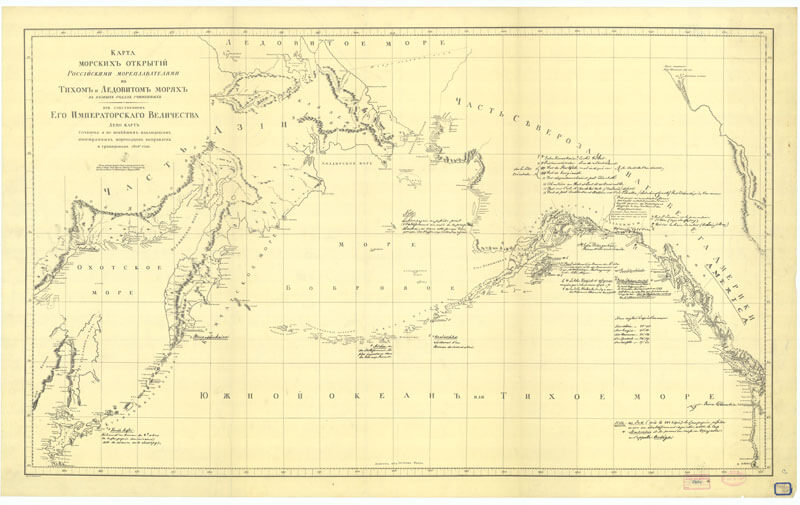

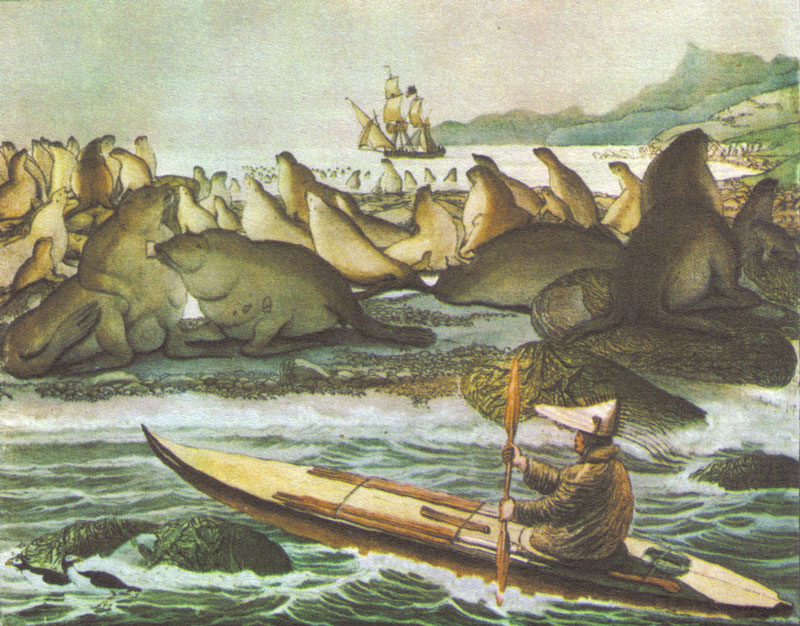

By the mid-18th century, colonial European endeavors were well underway in every corner of the world, and the sense of urgency to expand became pervasive among Europe’s ruling elite. Upon hearing reports from Siberian fur traders in 1741 that the Aleutian Islands and Alaskan Peninsula were abundant with fur seals and sea otters, the Russian government claimed these lands for Russia and set out to establish a colony in the New World. That colony became Russian America.

The distance between St. Petersburg, Russia, and the Alaskan mainland is approximately 7,500 miles, more than three times the distance from Los Angeles to New York City. And, the journey itself required transit across frigid seas, mountain ranges, and open plains. When coupled with the requirements of a colony — the management of resources and people needed to extract contested resources and turn a profit — establishing a Russian presence in North America was an extreme undertaking. Nevertheless, the lure of wealth outweighed the challenges, and by the late 1700s, a permanent Russian settlement and trading outpost was built on Kodiak Island, Alaska.

In 1799, the Russian-American Company was formed to take control of the Alaskan fur trade. Sponsored by the emperor of Russia, the company was responsible for creating permanent settlements throughout Alaska and along the west coast of North America and eventually administering the colony of Russian America.

The company hired Russian promyshlenniki (outdoors people, literally translated as "industrialists") to support hunting and trapping activities throughout the Aleutian Islands and the Alaskan mainland. While many of these promyshlenniki were hunters themselves, the company found it more lucrative to acquire furs using the knowledge and skills of the Aleutian Islands’ Indigenous Unangax̂ people. Prolific seafarers, Unangax̂ hunters were more skilled than the Russian promyshlenniki and were key to the success of the fur trade. Unfortunately, they were not treated equally. The Unangax̂ people (and later Tlingit communities of southeast Alaska) suffered poor working and living conditions within the colony and were unfairly compensated for their work.

In 1804, a settlement and fort were erected at New Archangel (today’s Sitka, Alaska) as the company headquarters. Over the next 60 years, additional outposts were established, including Fort Ross, California, and several in Hawai‘i. Maritime highways connected these settlements and were critical for the transport of goods to the company and the Russian mainland. To reduce shipping costs, the Russian-American Company built or purchased a number of their own vessels, including Svaytoy Nikolai.

As the company grew, so did the colony’s population. Promyshlenniki often married Indigenous women and had families who followed both Indigenous and Russian practices, traditions, and lifestyles. The blending of cultures through multiple generations led to new cultural dress, language, traditions, and religion. These novel practices became characteristic of many Alaskan communities by the 1820s and 1830s; although they also disrupted traditional Indigenous ways of life.

By the 1860s, the Russian-American Company began to fail, and Russia was losing interest in the colony. Over-hunting of sea otters contributed to declining profits, and trade in general faced increasing competition from British Canada and the United States. In 1867, the company’s holdings were liquidated and Russian America was formally disbanded and sold to the United States.

Today, remnants of Russian America are still present throughout Alaska and the west coast. Archaeological work continues to uncover materials from this time that offer new insight into Russian America and its communities.

By Madeline Roth, NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries

Published November 6, 2023