By Brad Barr, Expedition Coordinator, NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries Maritime Heritage Program

“My expectations were reduced to zero when I was 21. Everything since then has been a bonus.”

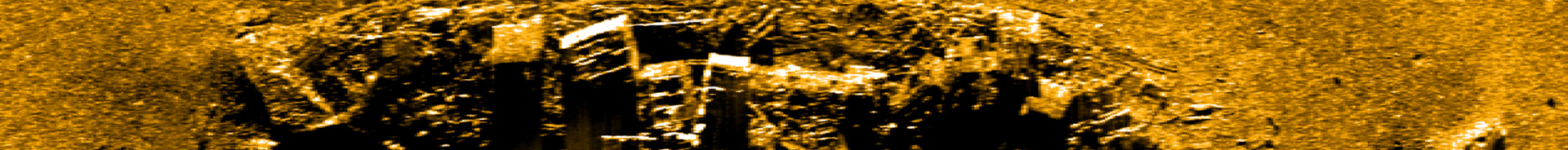

The bow of the shipwreck explored during the expedition, along with multiple fishing nets. Image courtesy of NOAA/MITech. Download largest image (jpg, 14.2 MB).

Upon finally embarking on this expedition, after more than a year and a half of delays due to COVID-19 and the various ships not being available due to redeployment for hurricane response and minor mechanical issues, our expectations for what might be accomplished when we finally were able to conduct the expedition were quite high (but we were very well prepared after two planned embarkation dates came and went).

In the previous phase of the project, conducted in September of 2019 on the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Bear, we felt quite successful in finding a shipwreck of generally the same length and beam of that storied vessel located near where the U.S. Revenue Cutter Bear was reported to have sunk. Our curiosity was heightened by a high-resolution side scan sonar image of that wreck which presented somewhat vague images of elements that were challenging to identify.

We knew we had to go back to get a closer look, but “when” we could do this was the big question. As we awaited our chance to do this, managing expectations was our primary challenge. When we finally did see what was hinted in that side scan sonar image, would the things we observed be consistent with what we had learned about how the ship was constructed and refit at least three times over the last few decades of her service and how she appeared when she was lost at sea in 1963?

Arriving at the general location of the shipwreck, the first and most critical task was to find it again. Notwithstanding the highly precise position we had obtained from the previous survey, we approached the location with some anxiety. U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Sycamore, which ably served as the platform for this phase of the mission, has installed onboard a sophisticated depth sounder, and a highly trained bridge crew to operate it, but it is limited to identifying what is only directly below the transducer, what is called a “single-beam” echo sounder. Unlike the side scan sonar system used to find the wreck originally, which employs a swath of multiple sound pulses to provide an image of the seabed, the depth sounder on Sycamore emanated only one, offering fewer chances to capture a reflection of the sound pulse it produced.

However, after the first pass over the estimated position, and a second, we observed an elevated feature on the uniformly flat, sandy bottom that could only be the wreck. We were much relieved, and could now proceed with launching the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) we had on the deck ready for deployment.

The launch and recovery of Pixel, the very capable ROV we were relying on to provide the detailed and high-resolution video of the wreck we were documenting, was hardly a challenge for the skilled and experienced deck crew of Sycamore. This ship is one of the Coast Guard’s “Juniper Class” ocean-going buoy tenders, built to service the many massive offshore buoys that aid navigation in these waters. So, safely and efficiently handling this considerably smaller ROV was not particularly challenging.

The mission of maintaining these important aids to navigation also requires Sycamore to be highly maneuverable and able to hold position without relying on anchoring, which is also a critical capability for conducting ROV operations. The ship was designed specifically for this task, equipped with special bow and stern thrusters and a variable pitch propeller, all computer controlled, to maintain the ship’s position and heading…what is called “dynamic positioning” (DP).

While the weather we ultimately encountered tested the limits of Sycamore’s DP capabilities, its performance in this “station-keeping” was pretty much flawless under the watchful eye of the experienced and well-trained bridge crew. While Sycamore was selected by the U.S. Coast Guard for this mission because it possessed the capabilities required for the safe and efficient deployment of the ROV system, we were nonetheless impressed at how well she performed under some very challenging sea conditions.

Fishing nets and other debris imaged near the explored shipwreck. Image courtesy of NOAA/MITech. Download largest image (jpg, 17.8 MB).

Once we were solidly holding station over the wreck, Pixel was launched. As we saw the seafloor come into view on the computer monitors, we once again had some anxious moments finding the wreck, even though we were certain it was nearby. While the underwater visibility was very good (for the western North Atlantic), we encountered strong bottom currents that often challenged the capabilities of the thrusters mounted on the ROV that maneuvered it through the water.

Once the shipwreck was observed looming in the distance, we all gave a sigh of relief. As we approached more closely, it became immediately apparent that the integrity of the wreck was not quite as expected. While the bow was still largely intact, the hull had experienced the ravages of time, exacerbated by what appeared to be considerable damage from mobile fishing gear. Torn fishing nets and what appeared to be pieces of foot ropes and roller gear were observed around and throughout the wreck, entangling many elements of what remained of the ship’s largely disarticulated hull and highly disturbed internal structural components. There was a large twisted tangle of net with small buoys floating upright, attached to something within the bow, which at first seemed to be the stub of a mast, but upon closer investigation, was just net and buoys. These nets, which often can be seen in side scan sonar images, were not apparent in the one we collected during the survey mission in September of 2019, so this was not what we expected to see.

Constantly adjusting to this unexpected challenging bottom-current regime, which varied considerably in speed and direction over time, we set about comprehensively collecting video of the wreck from as many perspectives and angles as possible. In preparation for the mission, we conducted extensive archival research on Bear, collecting construction plans from the National Archives, Coast Guard Archives, and Mystic Seaport library, as well as ships’ logs, historic images, movies in which Bear was featured, and other primary source documentation. We also had a small library of books written about Bear that also provided some insights on its construction and history.

This archival information was used throughout the expedition to focus our video documentation on features of the wreck that could help document its identity. Over the next three days, this cycle of launch and recovery of Pixel was repeated, and we were able to collect more than 30 hours of 4K and HD video, consuming more than 7 terabytes of data storage.

Toward the end of the third day, we met with Sycamore’s captain and executive officer, who had been carefully watching the approach of a low-pressure system from the south and west. With the forecast of potentially 13-foot seas, presenting sea conditions that even the highly capable Sycamore could not safely support our ROV operations, it was decided we should head for land. Given how far offshore we were and the transit time to even the closest port, it was unlikely we could return to the site within the time allotted to the mission in the ship’s busy schedule, so we kept Pixel on the bottom for as long as possible that final day, recovered it as the seas were building, and battened down the equipment as we prepared for a sloppy ride back to Sycamore’s home port of Newport, Rhode Island.

While we could have collected even more documentation of the wreck if not for the weather, what we did collect was sufficiently comprehensive to inform the identification of the wreck.

Did we find Bear? Well, we still have the long work ahead to review and evaluate the 30 hours of video and still images collected. This is a painstaking process that requires both time and expertise – to accurately interpret what we saw in order to answer this most important question.

To accomplish this, we are empaneling an “evaluation team” of maritime archaeologists and historians from our partner agencies, NOAA Ocean Exploration, the U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office, our own in-house archaeologists and historians at the NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries’ Maritime Heritage Program, and others with appropriate knowledge and expertise, to help us interpret and evaluate the data collected.

At some point in late July, this team will convene, review the findings, and arrive at a consensus on whether this “unidentified wreck” is Bear or some other very interesting similar ship lost at sea in these often inhospitable waters of the western North Atlantic.

While this may be somewhat unsatisfying, particularly for those of us who have been pursuing the last resting place of this iconic and most historic vessel for more than a decade, the work continues. This purposeful and systematic approach to evaluating the wreck site is essential.

We did not find anything one would expect might have the name of the ship on it. The ship’s bell was removed after Admiral Byrd returned from his second Antarctic expedition. The transom, where the name “BEAR” was proudly displayed during its 89 years of meritorious service, is no longer intact…or even identifiable as a transom. Bear had a very distinctive figurehead of a polar bear. The original was, again, removed by Admiral Byrd and donated to the Mariners Museum in Newport News, Virginia. While a replacement figurehead was installed on the bow when Bear was lost in 1963, it was unfortunately not observed anywhere in the wreckage.

In contrast to our expectations, the wreck was quite extensively disturbed, so many features we hoped to see are not in the position described in the plans and archival information, and may have been carried off in fishing nets and dumped elsewhere when the nets – that survived being dragged through the shipwreck - were hauled back. What remains is only the bow section (which is reasonably intact), what appears to be the lower deck and bilges of most of the rest of the ship, a very disarticulated stern section, and debris strewn around the entire site.

We have only what remains of the wreck for clues to its identity, but this may be enough to the skilled eyes of knowledgeable maritime archaeologists and historians. When the evidence is evaluated, we all will find out whether what has been discovered is the final resting place of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Bear.

Clearly, none of this work could have been accomplished without the support and involvement of the project partners. We would like to express our deep appreciation to the U.S. Coast Guard, for providing us with a highly capable ship and experienced and enthusiastic officers and crew. For those eight days at sea, Sycamore stood tall in its unaccustomed role as a research vessel, and performed admirably. Sycamore is a vital asset for the Coast Guard’s First District, maintaining aids to navigation from the Canadian border to northern New Jersey, so dedicating this time to our mission is especially gratifying, demonstrating their deep and longstanding commitment to our search for Bear, what is considered the most important vessel in their long and compelling history of service to the American people.

We are also most grateful to NOAA Ocean Exploration, who provided funding for the expedition. They showed great patience in accommodating the many delays and postponements keeping us from finally being able to spend the funds they granted to us in 2018, while providing enthusiastic support and encouragement. Additionally NOAA Ocean Exploration made available to us the services of an excellent Web Team that helped keep the public aware of what we were doing, and they accomplished this most efficiently and artfully.

We would also recognize the many contributions of our ROV Team, Marine Imaging Technologies, for also enduring the many delays, but ultimately providing expert ROV operations on this expedition. Also, our thanks to the NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries for their support of the expedition, and the Maritime Heritage Program personnel who contributed significantly to making all this happen.

The search for Bear did not just begin when these most recent expeditions were conducted. As detailed elsewhere on this website, the search began, in earnest, with the surveys conducted around 1979 by Harold “Doc” Edgerton — who is credited with the invention of side scan sonar — and his work with cadets at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy.

Countless others have been involved since Doc Edgerton’s initial work, each contributing to the body of knowledge upon which we have relied for this and our previous “Bear Hunt” expeditions. No one person, or one organization, can accomplish such things alone, and we express our deep and abiding gratitude to all these people on whose shoulders we stand today.

Published July 6, 2021