By Amanda Evans, Coastal Environments, Inc.

Imagine trying to put together a jigsaw puzzle, but you only have a handful of pieces. You don’t know how many pieces you need to complete the puzzle. You don’t know what shape the puzzle is supposed to be, and you have no idea what the final picture will look like. In fact, you’re not quite sure the pieces you have are all from the same puzzle.

Archaeologists study how people lived in the past. They do that by finding and examining the things that people in the past made. These artifacts, everything from stone tools to pyramids, are like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. With enough pieces, we can see the overall picture. Sometimes, the more pieces we find, the more we realize the picture isn’t what we thought it was at first. And sometimes, we find a piece that suggests there’s a whole other puzzle we know nothing about. Yet.

This project is starting from a handful of puzzle pieces that tell us that people were living along the northwestern Gulf of Mexico and coastal Texas and Louisiana as early as 13,000 years ago. Archaeologists refer to these early people as Paleoindians. We know they hunted and gathered food and moved around frequently. We also know that sea level was lower then than it is today, so there was more land available for these early people. We don’t think they used a lot of coastal resources, like oysters, shells, or saltwater fish, but maybe that’s because we haven’t been looking in the right places. The shoreline, bays, and estuaries where people could have fished or collected food are now underwater. Sea level rise caused by the melting of the glaciers at the end of the last glacial period drowned the land that people lived on thousands of years ago.

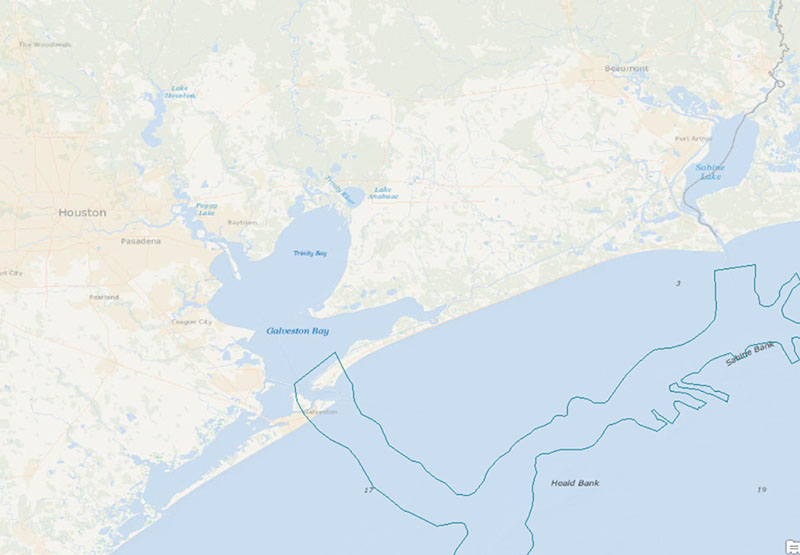

Geological mapping shows the broad extents of the former, incised Sabine and Trinity/San Jacinto River Valleys (after Simms et al., 2008). Image courtesy of Paleolandscapes and the ca. 8,000 BP Shoreline of the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf. Download larger version (jpg, 344 KB).

Our project is not the first to consider that archaeological sites may be buried and underwater on the continental shelf. Previous research in the 1970s, 1980s, and 2000s has identified what to look for and the best methods to use when looking for sites. In fact, 106 sediment cores have been collected specifically for archaeology offshore of Texas and Louisiana. It sounds like a lot but remember that we’re looking at over 40 million acres of seafloor. On land, archaeologists start searching an area by digging shovel tests. The cores give us similar information, but the 106 cores already collected cover the same surface area as only 11 shovel tests. If we want to figure out the shape of this puzzle, we desperately need to find more pieces.

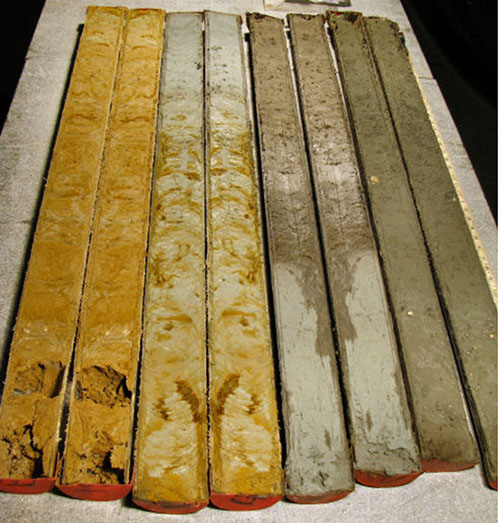

A split core, recovered in 2010, shows the transition from modern marine sediment (top right), through the Pleistocene clay (lower left). Image courtesy of Paleolandscapes and the ca. 8,000 BP Shoreline of the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf. Download larger version (jpg, 401 KB).

Our objective is to add more information to this overwhelming puzzle. There aren’t enough pieces to let us ask questions about past human behavior yet. First, we have to explore uncharted parts of the landscape. Like the naturalists and scientists of the past, we have to map what was there, and collect samples that tell what that place was like. If we build a better picture of what life would have been like, we can start to ask questions about the people that would have been there.

Simms, A.R., J.B. Anderson, K.T. Milliken, Z.P. Taha, and J.S. Wellner