By Betsy Petrick, NOAA Teacher at Sea

June 27, 2019

Yesterday was a doozy of a day, I think everyone on the ship would agree. One frustrating setback after another had to be overcome, but one by one, each problem was solved and the day ended successfully.

The first discovery yesterday morning was that the ship’s pole-mounted ultrashort baseline tracking system (USBL) had been zapped with electricity overnight and was unusable. This piece of equipment is a key piece of a complex system. Without it, we would not know precisely where the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) was and we wouldn’t be able to place experiments without fear of damaging the shipwrecks, nor could we control the sweeps of the ROV over the shipwrecks for accurate mapping. The scheduled dive time of 13:30 was out of the question. There was even talk of returning to port to get new equipment. This would cost the expedition $30,000-$40,000 for a full 24-hours of operation, and no one wanted to do this.

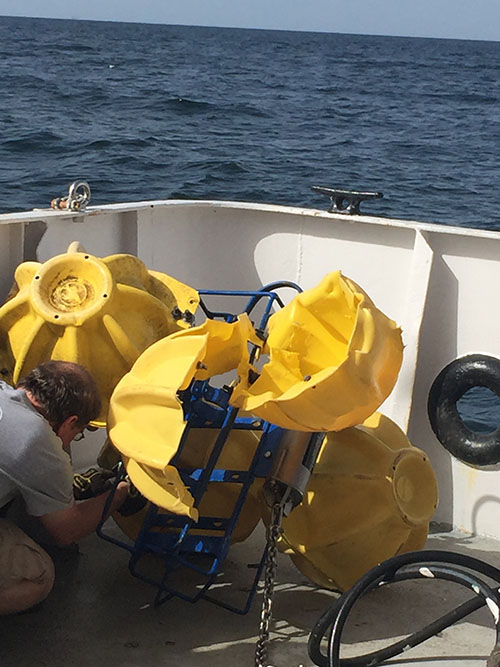

Max, the team’s underwater systems engineer, worked his magic, and replaced the USBL—which tracks any underwater device the ship sends to the seafloor. This required an expert’s knowledge and some tricky maneuvers. Once this was resolved, the next step was to send a positioning beacon down to the seafloor to calibrate the signal from the ship to the ROV so that we would be able to track it precisely. The deployment went without a hitch. But, when the lander floated to the surface, we noticed it was floating in an abnormal way. When we hauled it aboard, we discovered that one of the glass floats had imploded—probably due to a material defect under the intense pressure at 1,200 meters (3,940 feet) below sea level—and all we had left of that unit was a shattered mess of yellow plastic.

This is all that was left of the lander flotation shell after the glass float imploded. Image courtesy of Betsy Petrick. Download larger version (jpg, 2.3 MB).

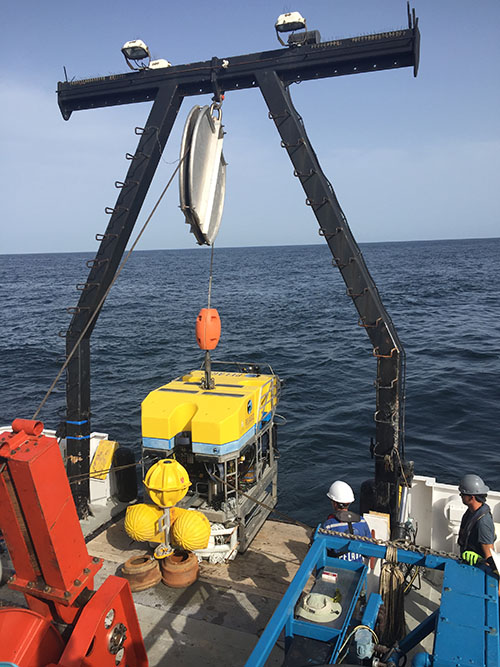

In spite of that, the calibration was complete and we could send the ROV on its mission. We loaded the microbial recruitment experiments (MRE) onto the back of the ROV, along with a lander and two heavy brake drums for weight. These would hold the lander on the seafloor until it was time to call it home on a future date. This was the exciting moment! The crane lifted the ROV Odysseus off the ship deck and swung it out over the water. But in the process, the chain holding the weights broke and, with a mighty groan from all of us watching, both of them sank into the sea. Back came the ROV for a new set of weights. Luckily nothing was damaged.

By 17:45, five hours after the scheduled time, the ROV went over the side for a second time successfully. Once this was done, Dr. Hamdan was able to crack a smile and we tentatively celebrated. Now we had an hour to wait for the ROV to reach the seafloor again and begin its mission of deploying and retrieving MREs. Inside the cabin of the ship, some of us sat mesmerized by the drifting phytoplankton on the big screen, while up in the pilothouse, the captain was on duty holding the ship in one spot for as long as it took for the ROV to return.

The team works to attach the landers to the back of the ROV. Image courtesy of Betsy Petrick. Download larger version (jpg, 4 MB).

The crane lifts the ROV and its experimental cargo into the ocean. Image courtesy of Betsy Petrick. Download larger version (jpg, 4 MB).

Today I saw what scientific exploration is really like. As someone said, “Two means one, and one means none,” meaning that when you are out at sea, you have to have a second or even a third of every critical piece of equipment because something is inevitably going to break and you will not be able to run to the store for a new one. Failures and setbacks are part of the game. As a NOAA Teacher at Sea, I am looking at all that goes on during an expedition through the lens of a classroom teacher. Yesterday’s successes were due to clear-headed thinking, perseverance, and teamwork by many. These are precisely the qualities I hope I can foster in my students.