By Melanie Damour, Marine Archaeologist

July 5, 2019

Site 15470 stern with draft mark. Image captured by ROV Odysseus, courtesy of Microbial Stowaways. Download larger version (jpg, 6.1 MB).

As the Microbial Stowaways project fieldwork comes to a close, we reflect on what we discovered over the past week. Two copper-sheathed, wooden-hulled shipwrecks—Site 15711 and Site 15470—give us glimpses into life aboard 19th century sailing ships and will tell us how their presence influences microbial biodiversity in the marine environment. With the unexpected discovery of the ship’s bell at Site 15711 in the Viosca Knoll lease area—something we don’t often find on shipwrecks—we wondered what new and exciting discoveries awaited us at the second shipwreck, Site 15470 in the Mississippi Canyon lease area. Located more than 100 miles offshore and in water depths greater than 6,000 feet, we were struck immediately by the remoteness of this shipwreck… and its serenity. Far from the hustle and bustle of busy Gulf Coast ports and frequently traversed shipping lanes, the wreck and its debris offers a bit of an oasis in what is an otherwise vast expanse of featureless muddy seafloor in every direction. Still, faunal residents were few and far between at this site more than a mile deep as compared to shallower sites which are often teeming with life. Among the larger resident fauna, we saw one anemone and one crab… and the crab did not appear thrilled with our sudden intrusion into its tranquil spot.

Site 15470 iron knees. Image captured by ROV Odysseus, courtesy of Microbial Stowaways. Download larger version (jpg, 6 MB).

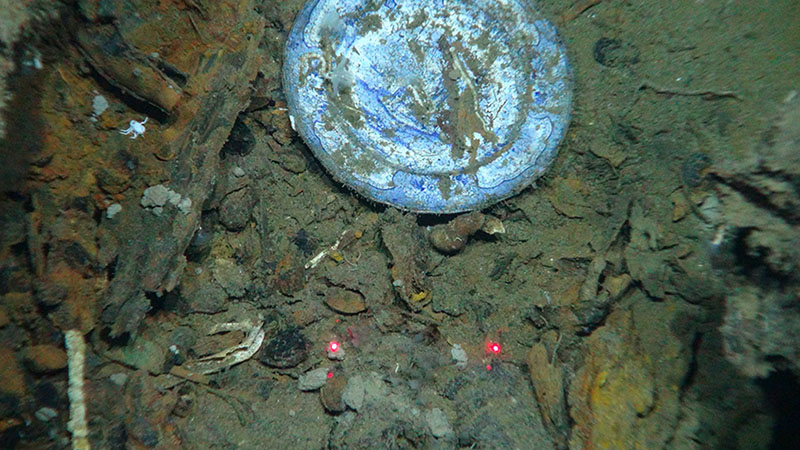

Artifacts found at Site 15470 at ~1,800 meters (~5,905 feet) depth. Image captured by ROV Odysseus, courtesy of Microbial Stowaways. Download larger version (jpg, 6.6 MB).

The hull measures a little more than 100 feet in length and approximately 35 feet in width. The bow and stern are mostly intact although the rudder was not observed. A single draft mark—the number “6” indicating 6 feet—remains on the starboard side of the stern post. A rudder gudgeon, used to hold the rudder in place and allow it to swing on its adjoining pintle, could be seen just above the draft mark. From what we could see, very little wood remains except for what might lie hidden under the soft sediments that have settled inside the hull. What really excited me, and my fellow marine archaeologist Doug Jones, was the discovery of iron knees used in the construction of this wooden-hulled sailing ship. It is not a method of ship construction that we have commonly seen on the 19th century deepwater shipwrecks we’ve investigated in the Gulf of Mexico to date. Over many centuries, traditional wooden ship construction utilized knees made of wood. Knees provide internal structural support for deck beams and frames, among other functions, and were usually fashioned from the natural curvatures in trees such as where two large branches met. The development of iron knees appears to have begun in Europe in the mid-18th century and eventually spread to shipbuilding in North America and other areas in the 19th century. This is a tantalizing clue as to the vessel’s age. Among the artifacts observed are several glass bottles of various shapes and sizes, a telescope or “spyglass”, a spoon, and ceramic plates, some exhibiting the transfer print style (blue and even red varieties). The hull’s construction and the artifacts carried on board each serve as pieces in the jigsaw puzzle as we slowly reconstruct this vessel’s story, from nationality and function to her role in human history and, perhaps, what caused her to slip beneath the waves. There is much to be learned about these sites, from the archaeological investigations to studying the shipwrecks’ influence on marine microbial ecology, and we are only just beginning to assemble those puzzle pieces.

Image of a plate found at Site 15470. Image captured by ROV Odysseus, courtesy of Microbial Stowaways. Download larger version (jpg, 13.2 MB).