By Dr. Leila Hamdan

Associate Professor

School of Ocean Science and Engineering, University of Southern Mississippi

The focus of research in our lab is microbial ecology, which probes population genetics, the relationship of microbes to each other and other living things, and their interactions with environment. This area of research asks three basic questions:

We have studied this topic in every ocean basin and in shallow and deep-sea systems. Our work has revealed microorganisms are cosmopolitan and diverse and that their communities form from interaction with the physics, geology, biology, and chemistry of marine environments. In 2011, however, my research took a sharp turn when I met my first marine archaeologist, and my co-principal investigator on this expedition, Melanie Damour.

Principal investigators Dr. Leila Hamdan and Melanie Damour preparing push cores for sediment collection. Image courtesy of Hamdan Lab. Download larger version (jpg, 3.1 MB).

On the surface, it sounds completely esoteric: deep-sea shipwreck microbial ecology. In reality, shipwrecks are logical places to study microbial life and ideal to monitor the impacts of human activities on the microbial ecology of the seafloor. At the time I met Melanie, I was interested in studying how an oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico impacted deep-sea bacteria. Melanie was wondering how bacteria were impacting deep-sea shipwrecks in the Gulf of Mexico. Her ideas formed around how biofilms preserve (protect) or degrade (consume as a food source) shipwrecks. I had studied the deep sea for many years, but had no idea that there were thousands of shipwrecks already discovered and more that remain hidden. We both wanted to tell a story about the shipwrecks, and the microbes shaping life on them.

This expedition involves scientists from disciplines that rarely intersect: marine archaeology and microbial ecology. This unique collaboration allows us to look at the seafloor from different scales and perspectives to understand the role of historic shipwrecks as deepwater ecosystems. The majority of scientific research of the seafloor occurs without consideration of the “built environment.” Although numerous historic shipwrecks are documented on the seafloor, no studies have addressed how they impact the distribution of microbes across space and time. The work we do together during Microbial Stowaways is far from esoteric—we are asking a practical question: is the microbiology of the deep sea, a place once considered remote, changed by the built environment?

My science has grown richer from collaborating with marine archaeologists. My new knowledge about how numerous human-built structures are on the seafloor allows me to challenge what I assumed about the deep sea. It is not remote, but instead in contact with our cultural history. It is a thrill to work with a colleague whom I can learn from, and learn with, and we are excited to share this exploration with others.

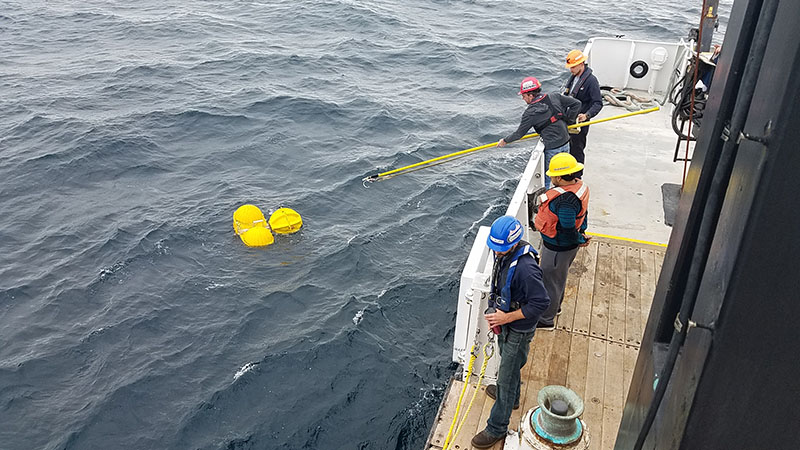

Experiment deployment aboard R/V Point Sur. Image courtesy of Microbial Stowaways. Download larger version (jpg, 4 MB).

Recovering acoustic landers from the seafloor aboard R/V Point Sur. Image courtesy of Microbial Stowaways. Download larger version (jpg, 4.1 MB).