By Eric Collins, Professor in Oceanography - University of Alaska Fairbanks

July 30, 2019

Like plants on land, sunlight-powered phytoplankton in the sea produce oxygen as a byproduct of their photosynthetic metabolism. And, like animals on land, animals and other heterotrophs in the sea respire that oxygen by breathing.

Unlike on land, where the wind can transport freshly produced oxygen all around the world in a matter of days, it can take many years for oxygen to be transported through the ocean. In fact, oxygen in the deep sea can be over a thousand years old, produced by plants and phytoplankton that are now long dead. This is because oxygen doesn’t diffuse directly from the atmosphere into the deep sea, instead it has to be transported there by oxygenated surface water that sinks down… down… down to the bottom of the ocean. This process usually happens at the poles as cold, oxygen-rich water sinks and pushes warmer, oxygen-poor water up and around in what is known to oceanographers as thermohaline circulation. This means that if the oxygen gets used up somewhere in the deep sea due to respiration, it can take over a thousand years for it to be replenished by the global thermohaline circulation!

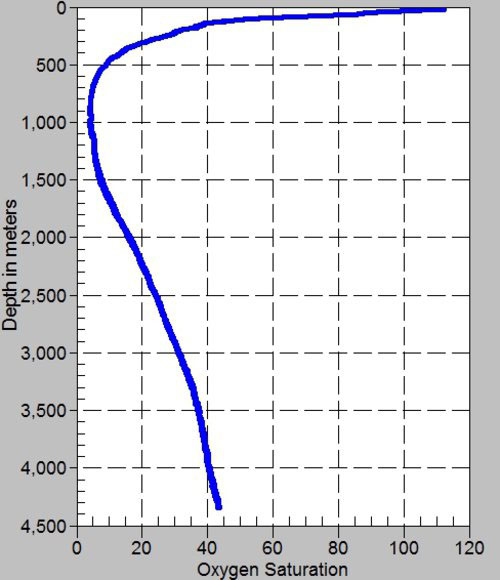

Image of the water column depth on the vertical axis and the amount of oxygen on the horizontal axis. Extreme low concentrations of oxygen (Oxygen Minimum Zone) can be seen at 750 meters (2,460 feet). Image courtesy of Eric Collins, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Download image (jpg, 77 KB).

The deep Gulf of Alaska is one of several places in the world ocean called Oxygen Minimum Zones (OMZs) where the oxygen gets used up faster than it gets replaced. This causes depletion of the oxygen, which in some places can even go anoxic, meaning there is no oxygen there at all.

Aboard Sikuliaq, we have a sensor on the CTD rosette that measures the amount of oxygen in the water, so we can get a profile of oxygen in the water column each time we take a CTD cast. At our current location, the oxygen reaches a minimum concentration at a depth of about 750 meters (2,460 feet). The amount of oxygen there is about five percent of the amount in the air at the surface – that’s equivalent to the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere at a height of 20 kilometers (or about twice as high as Mount Everest!). Unfortunately, the sizes and numbers of OMZs are increasing in the ocean as a result of global warming and pollution, meaning that animals in the deep sea will need to hold their breath or move out of these regions to survive.

Eric Collins is taking a water sample from the CTD. Image courtesy of Katrin Iken, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Download larger version (jpg, 569 KB).