By Sarah Hardy, Associate Professor - University of Alaska Fairbanks

August 3, 2019

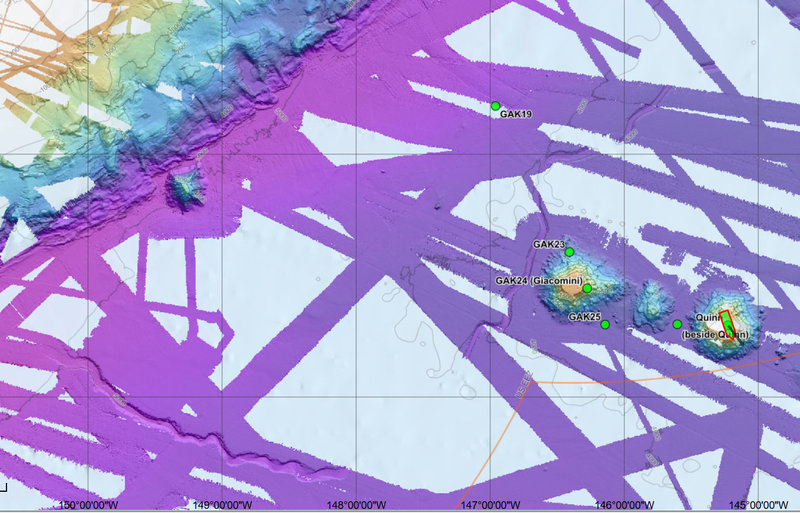

Bathymetric map of seamounts in the Gulf of Alaska. Color shows different bottom deptsh and the white areas indicate regions where the seafloor has not yet been mapped. Image courtesy of Steve Roberts, UAF. Download larger version (jpg, 677 KB).

I’ve been a scientist for a pretty long time now, and one of the things I’ve learned over the years is that the more you learn, the more you realize how little you actually know. I study infauna, which are mostly microscopic organisms that live within the sediments at the seafloor. In other words, I’m a biologist, but I also need to understand something about the habitat in order to understand how these organisms got there and what they are doing. So that means I’ve spent a fair bit of time studying other sciences like physics, chemistry, and geology, and on these topics, you might say I know just enough to be dangerous. I sometimes think if I hadn’t been a biologist, I would have studied geology – I always wish I knew more about the landscape and I feel the same way out here. But without an actual geologist on board, we sometimes have to use our collective (rusty) knowledge to make some educated guesses.

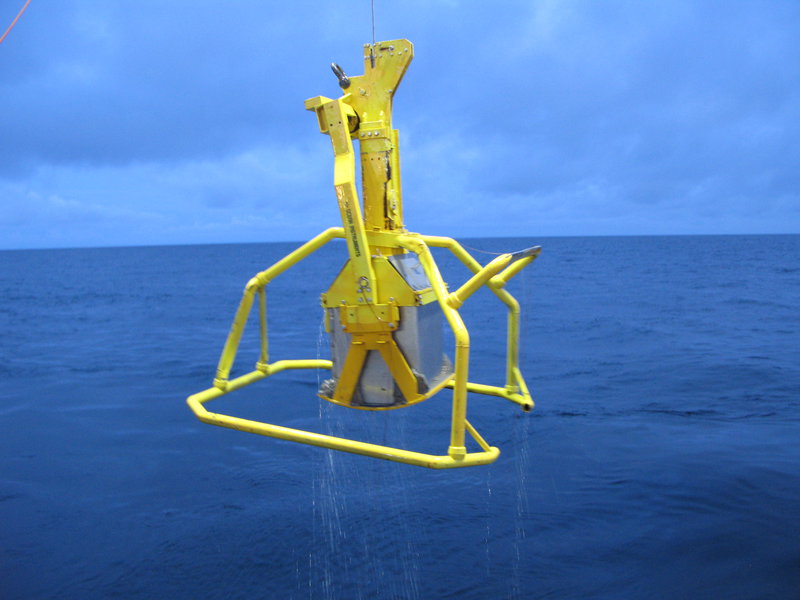

The box corer is like a gigantic cookie cutter that can take out a chunk of seafloor mud. Image courtesy of Sarah Hardy, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Download larger version (jpg, 5.8 MB).

These seamounts are more than two miles high, stretching from the abyssal seafloor at more than 4,000 meters (2.5 miles) deep to within a little less than half a mile from the sea surface. For seafloor organisms that live well below the depths where plant (or rather algal) life can grow, a seamount is like a big ladder you can climb up to get closer to where the food is. Seamounts are also at least partly covered with rock, so they also provide a totally different type of habitat than most of the muddy deep seafloor, meaning totally different critters can live in the neighborhood than you might otherwise find out here in the deep sea.

So on the way out to the seamounts, we stopped at station GAK 19 to collect some samples on the abyssal plain because it’s nice to have some “background” information so we know how things are different on the seamounts. For me, this was a pretty interesting site. Partly, that’s because the steel frame of the box core we use to sample sediments actually imploded at the 4,500-meter (2.8-mile) sampling depth, but that’s another story...

One of the heavy-duty metal pipes of the box corer that got crushed under the immense pressure at 4,500 meters (2.8 miles) depth! Image courtesy of Sarah Hardy, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Download larger version (jpg, 5.0 MB).

En route to GAK 19, I looked at the high-resolution bathymetric maps of the area (think topographic maps, but underwater) and saw what looks like a river bed on the seafloor, about 300 meters (~985 feet) deep, meandering just like rivers do on land, all the way to the edge of the Aleutian trench. But this area has never been above sea level, so how did it form? My guess is that it was formed by a turbidity current—a massive underwater mudslide. But feel free to chime in if you know differently.

And THEN we brought up some mud. I was expecting the soft mud that is typical of the deep seafloor where things are pretty quiet from one day to the next. But when we dug in to our core sample, we found more evidence that this area has seen some action in the geological sense. Below the upper few centimeters of “normal” seafloor mud, we found multiple layers of different colored sand, which actually felt dry to the touch, kind of like that cool “kinetic sand” my two toddlers like to play with.

Turbidity currents appear in the sedimentary record as layers of stuff that doesn’t look like it should be there, so again I’m guessing we landed on some ancient mudslides. While this might seem like irrelevant information to a biologist, the size and type of sediment grains, and how they are deposited, have a major influence on the types of animals that will be found at a particular location. So now it’s time to put my biologist hat back on and see who’s at home...

The light sediment layer between the darker top and bottom layers tells a story of past geologic events. Image courtesy of Katrin Iken, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Download larger version (jpg, 4.2 MB).