By Russ Hopcroft, University of Alaska Fairbanks

Some areas of the Gulf of Alaska have been studied for zooplankton, the small water column drifting organisms that make up an essential part of the marine food chain, for decades; however, collections have generally been confined to the continental shelf area of the Gulf of Alaska (200 meters/656 feet maximum depth). In addition, most collections have focused on the so-called “net-plankton,” those types of organisms that are robust enough to be captured by fine-meshed nets. What we do know about the Gulf of Alaska’s dominant zooplankton is biased toward the most robust and abundant species in the surface layers, especially crustaceans such as copepods and krill, even over the deeper regions.

Deeper plankton net collections in the northern Gulf of Alaska are virtually absent due to the larger investment in time required to sample them. While crustaceans are immensely important in sustaining higher trophic levels (fish, birds, and mammals), they are not the only zooplankton that is ecologically important or contributes to the pelagic biodiversity of the system. In fact, the soft-bodied, gelatinous zooplankton such as jellyfish are often major predators in the marine system and our current lack of knowledge of these species tends to makes us underestimate their importance.

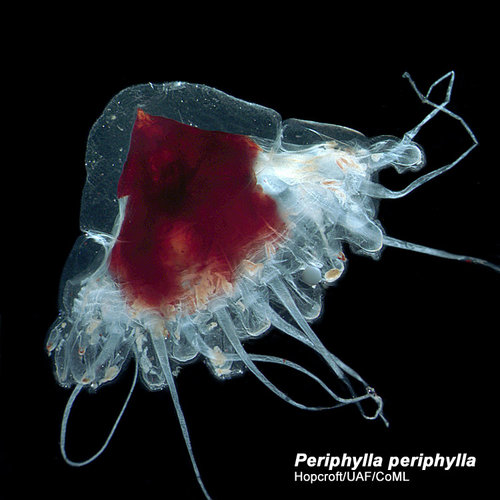

Periphylla sp. is a delicate jellyfish that can be found in the deeper waters in the Gulf of Alaska. Image courtesy of Russ Hopcroft, UAF. Download larger version (jpg, 176 KB).

Many jellyfish can produce harmful stings to humans upon contact, so it is easy to imagine how much worse such a sting can be for a small fish or even smaller crustaceans. It is also easy to imagine that there may be few other species higher in the food chain that will prefer to eat jellyfish because they are typically low-quality food and consist of mostly water. It has been argued that jellyfish are a “dead end” in the marine food chain; however, we cannot really evaluate this if we don’t have a good understanding of how many and which types of these gelatinous zooplankton organisms are out there. Furthermore, we believe there is a high chance that we will find species that have not even been described before in the Gulf of Alaska.

We will be using the remotely operated vehicle Global Explorer to carefully capture these fragile and elusive gelatinous zooplankton as well as take ultra-high-resolution imagery so we can describe these species morphologically and genetically, quantify their abundance, and observe their behavior in nature. The hydrographic upwelling processes that creates the upward flow of water from depth towards the upper water column along the seamounts has the potential to congregate these gelatinous species around the seamounts, which makes these pinnacles a valuable target area for exploration and discovery.

Beroe abyssicola is a comb jelly, which is a voracious predator in the deeper waters of the Gulf of Alaska up to the Arctic. Image courtesy of Russ Hopcroft, UAF. Download larger version (jpg, 136 KB).